Taxén, Lars; Lilliesköld, Joakim: Images as action instruments in complex projects; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 5, pp. 527-536.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.05.009

Images are quite powerful. I hate motivational posters which a distant corporate HQ decorates every meeting room with, but I once saw the department strategy visualised by these folks, they include all employees and the group dynamic is unbelievable. Later on they cleaned the images, blew them up, and posted them around the company – of course, meaningless for an outsider but a powerful reminder for everyone who took part.

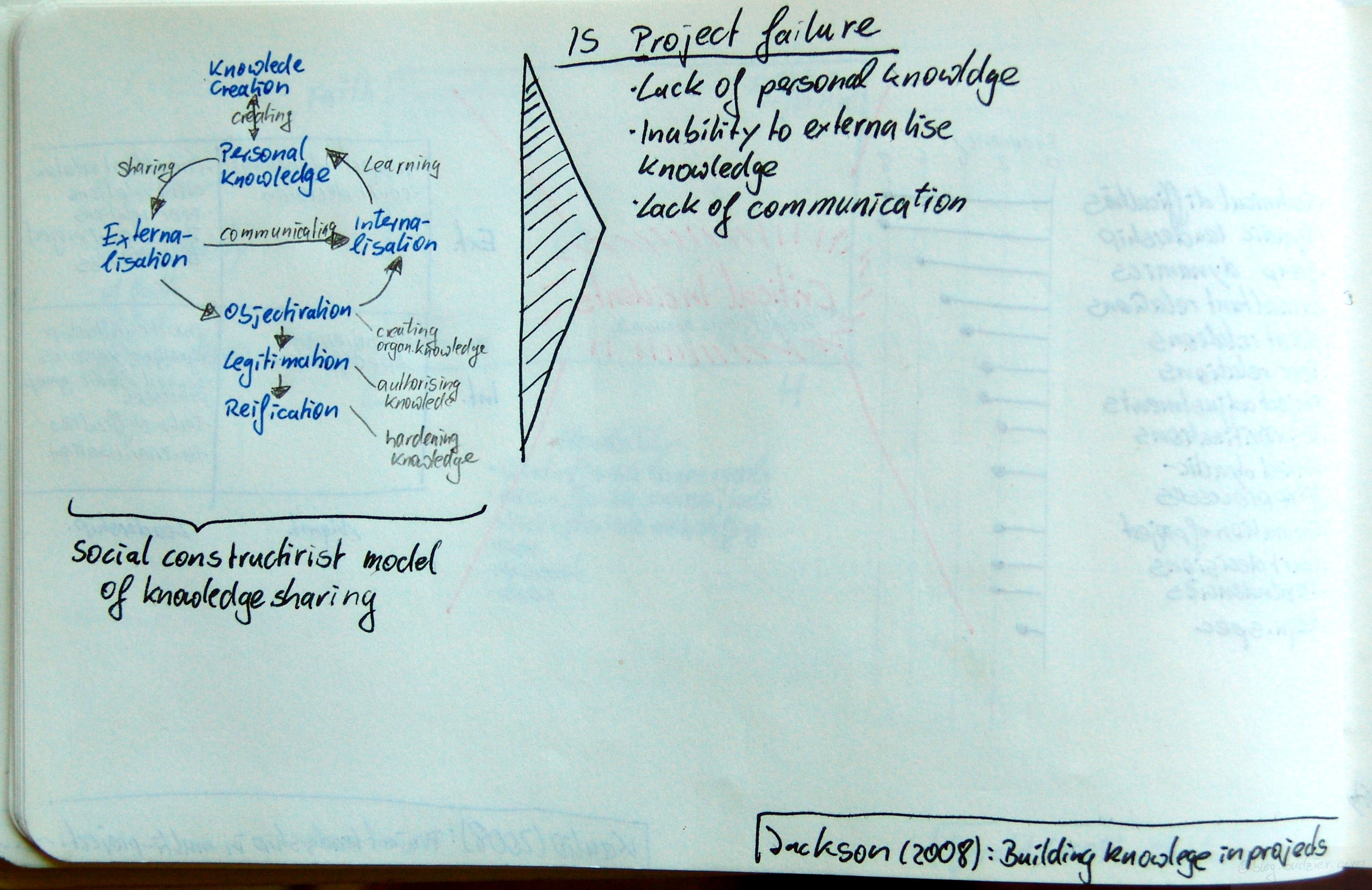

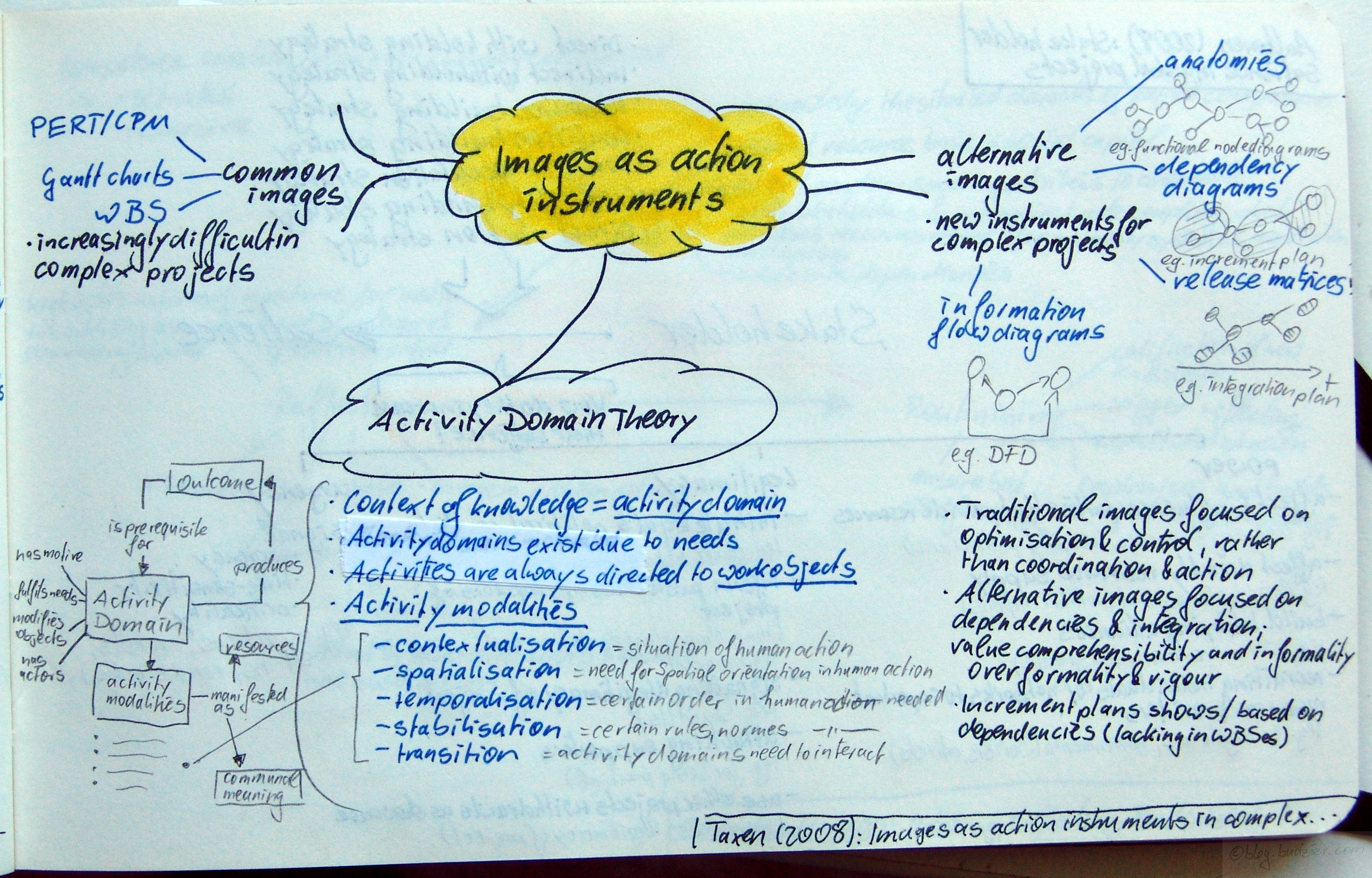

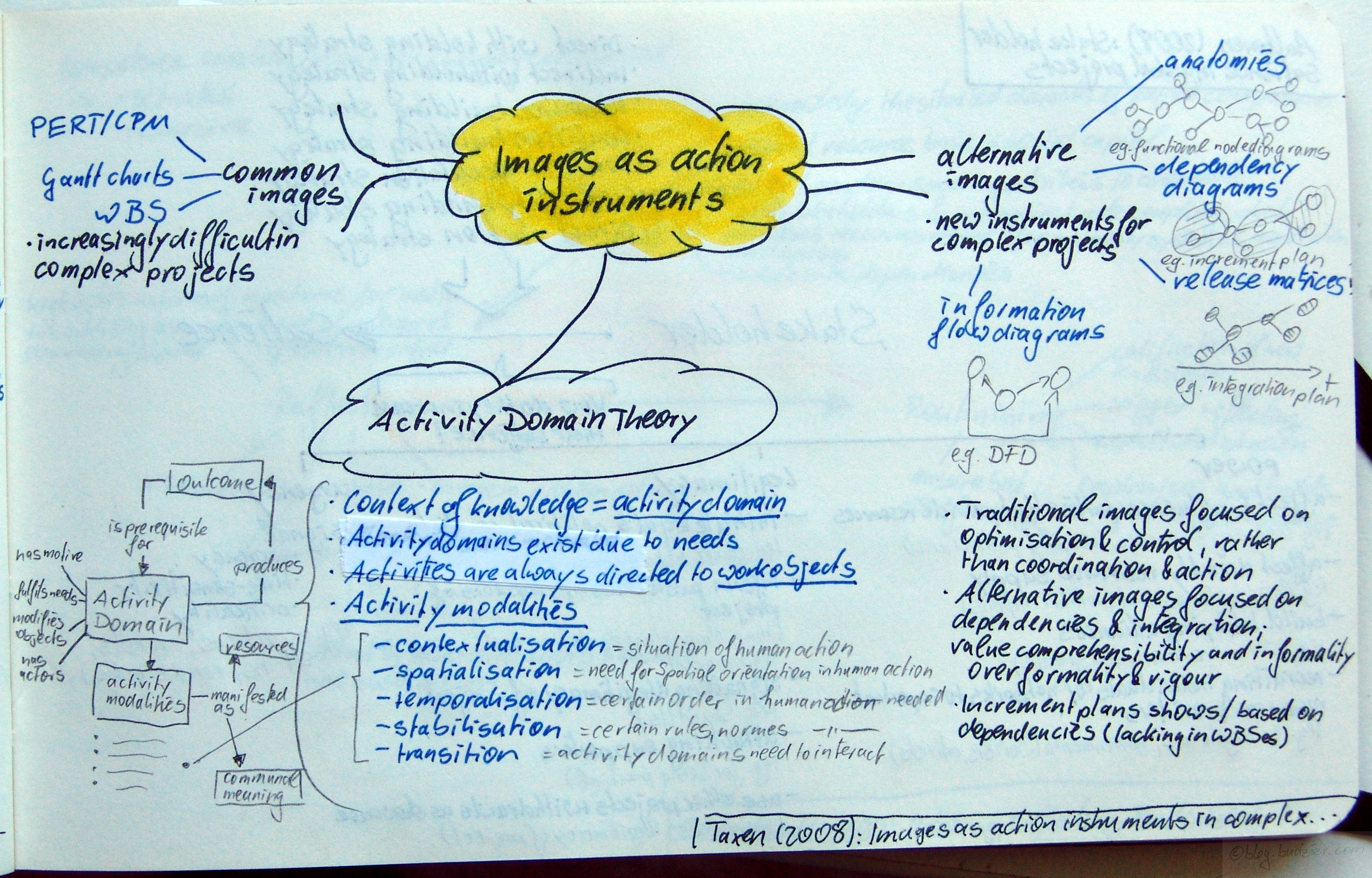

Taxén & Lilliesköld analyse the images typically used in project management. They find that these common images, such as PERT/CPM, Gantt charts, or WBS are increasingly difficult to use in complex projects, in this case the authors look into a large-scale IT project.

Based on Activity Domain Theory they develop alternative images better suited for complex projects. Activity Domain Theory, however, underlines that all tasks on a project (= each activity domain) have a motive, fulfils needs, modifies objects, and has actors. Outcomes are produced by activity domains and are at the same time prerequisites for activity domains. Activity domains have activity modalities, which can be either manifested as resources or as communal meaning. These activity modalities are

- Contextualisation = situation of human action

- Spatialisation = need for spatial orientation in human action

- Temporalisation = need for certain order in human action

- Stabilisation = need for certain rules and norms in human action

- Transition = need for interaction between activity domains

Useful images, the authors argue, need to fulfil these needs while being situated in the context of the activity. Traditional images focus on optimisation and control, rather than on coordination and action. Thus alternate images need to focus on dependencies and integration; on value comprehensibility and informality over formality and rigour.

Alternative images suited for complex project management are

- Anatomies – showing modules, work packages and their dependencies of the finished product, e.g., functional node diagrams

- Dependency diagrams – showing the incremental assembly of the product over a couple of releases, e.g. increment plan based on dependencies (a feature WBS lack)

- Release matrices – showing the flow of releases, how they fit together, and when which functionality becomes available, e.g., integration plan

- Information flow diagrams – showing the interfaces between modules, e.g. DFD