Kronmal, Richard A. (1993) „Spurious Correlation and the Fallacy of the Ratio Standard Revisited“, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society), 156 (3), pp. 379-392.

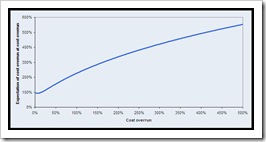

This has been on my mind for a while. A lot of our research uses looks at cost overruns as the variable to measure the project performance. More precisely we most often use Actual/Estimated Cost – 1 to derive a figure for the cost overrun. A project that was budgeted for 100 and comes in at 120 thus has +20% cost overrun. If the scale needs to be transformed, which in most cases it does, the simple Actual/Estimated ratio offers some advantages, i.e., figures being non-negative.

Most criticism for this comes from the corner of Atkinson (1999)*, i.e., that the holding the project accountable for its initial Cost-Benefit-Analysis (+Time) is an unfairly narrow view that ignores the value of building stuff itself, the wider and possibly non-quantitative benefits for the organisation and the wider and most likely non-quantitative benefits for the stakeholder community.

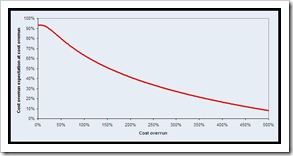

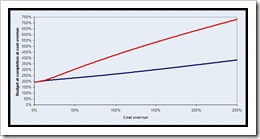

However, a second corner of critics has also a powerful argument. Ratios cause all sorts of statistical headaches. First, dividing a normally distributed variable by another normally distributed variable creates a log-normal distributed variable, i.e., it creates outliers that are solely an artefact of the ratios.

More importantly than distributional concerns are spurious correlations. This is an example from the article

„… a fictitious friend of Neyman (1952), in an empirical attempt to verify the theory that storks bring babies, computed the correlation of the number of storks per 10000 women to the number of babies per 10000 women in a sample of counties. He found a highly statistically significant correlation and cautiously concluded that ‚. . . although there is no evidence of storks actually bringing babies, there is overwhelminge videncet hat, by some mysteriousp rocess, they influencet he birth rate‘!“ (Kronmal 1993:379)

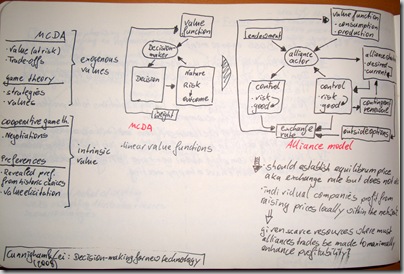

What happened in that example. The regression should have been the test of the number of storks and the number of babies in a county. The argument for the ratio is that it will control for the number of women in the county. The argument against it is that that creates a spurious correlation. Better would be an ANCOVA type structure. Or as the article puts it

„This example exemplifies the problem encountered when the dependent variable is a ratio. Even though Y, the numerator of the ratio, is uncorrelated with X, the independent variable, conditional on Z, the ratio is significantly correlated to X through its relationship to Z, the denominator of the ratio.“ (Kronmal 1993:386)

Three more observations are made in the article

- Using the two variables and their interactions instead of a ratio commonly makes for a worse model than using the ratio, particularly in stepwise regression models.

- Ratios are an interaction and can only be adequately interpreted in an equation that includes both of these variables (the main effects)

- Use a full regression model with interactions, then include the ratio if it adds to it

The final advice is

But what if the ratio is the ’natural quantity of interest‘, just like in our performance measurement?

The division of the outcome by the estimate is to remove its effect from the numerator variable. Kronmal questions whether „this is the optimal way to accomplish this“. He goes on further „…even when such rates are used, there is no reason not to include the reciprocal of the population size as a covariate. For other ratios, the purpose of the denominator is usually to adjust for it. In these instances, there is little to commend the use of this method of adjustment.“ (Kronmal 1993:391)

I will think about this a while, get in touch if you want to share thoughts on this.

* Atkinson, Roger (1999) „Project management: cost, time and quality, two best guesses and a phenomenon, its time to accept other success criteria“, International Journal of Project Management, 17 (6), pp. 337-342.