Boonstra, Albert: Interpreting an ERP-implementation project from a stakeholder perspective; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 24 (2006), No. 1, pp. 38-52.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2005.06.003

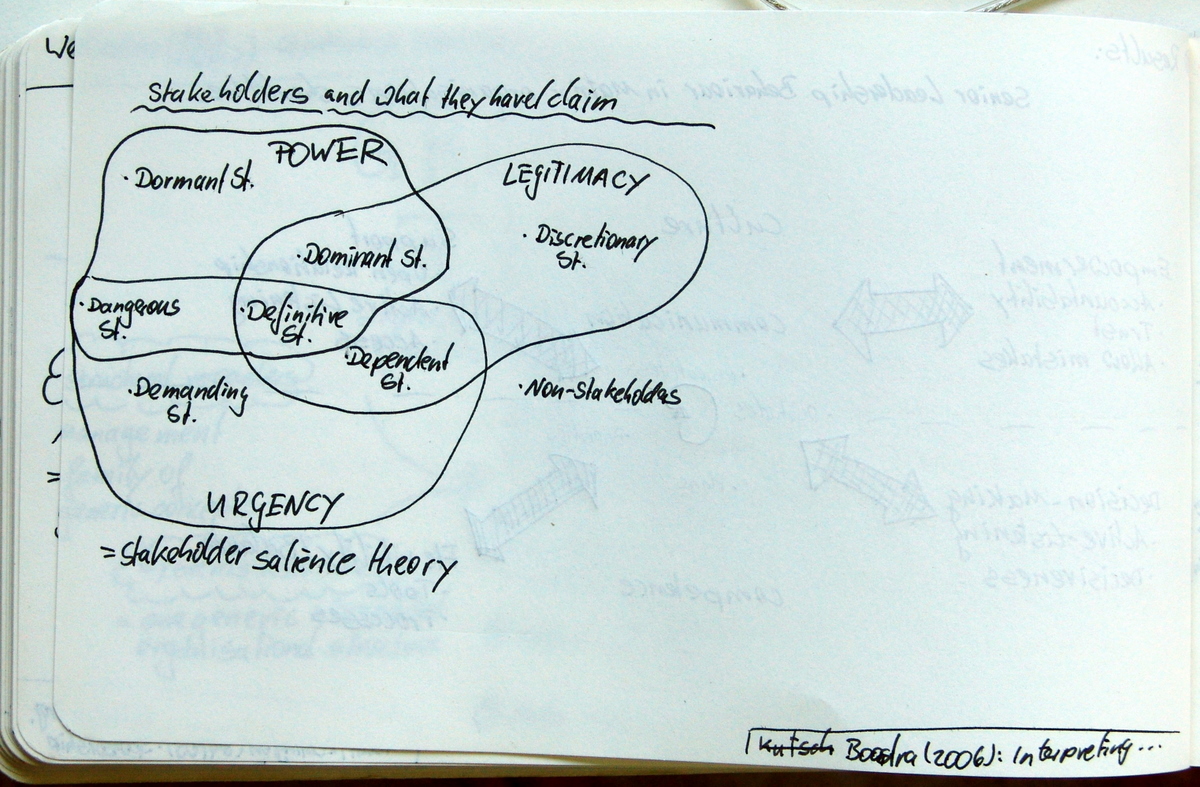

Boonstra analyses a case study from the stakeholders perspective using Stakeholder Salience Theory (Mitchell, Agle, Wood 1997). Stakeholder Salience Theory states that the prominence of a stakeholder (salience) is directly related to the cumulative attributes of power, legitimacy, and urgency.

Power (= exercise will against resistance) is explained with resource dependence theory, agency theory, and transaction cost theory. Resource dependence theory shows that managerial attentions is required if the project is depends on a critical resource owned by a stakeholder. Further managerial attention is required if opportunism can potentially occur in that relationship, as explained by agency and transaction cost theory.

Legitimacy (= compliance of activities and outputs with existing norms, beliefs, values is explained by population ecology and institutional theory. Population ecology states that projects not fulfilling stakeholders needs struggle to survive; whilst institutional theory observes that survival depends on legitimacy acquired from conformance or isomorphism. Thus legitimate stakeholders require managerial attention.

Urgency (= degree of need for immediate attention) is a general concept in several organisation theories but explicitly discussed in issue management and crisis management literature. Urgency has two distinctive attributes time sensitivity and criticality of the claim. Urgent stakeholders require managerial attention.

From Neville, Benjamin A.; Menguc, Bulent; Bell, Simon J.: Stakeholder Salience Reloaded – Operationalising Corporate Social Responsibility, in: ANZMAC 2003 Conference Proceedings, Adelaide 1-3, December 2003, pp. 1883-1889.

Based on these 3 attributes Boonstra identifies 8 types of stakeholders.

„1. Dormant stakeholders possess the power to impose their will on a firm but, by not having a legitimate relationship or an urgent claim, their power remains unused.

2. Discretionary stakeholders possess legitimacy, but have no power for influencing the firm and no urgent claims. There is no pressure to engage in a relationship with a stakeholder.

3. Demanding stakeholders exist where the sole stakeholder relationship attribute is urgency: those with urgent claims, but having neither legitimacy nor power.

4. Dominant stakeholders are both powerful and legitimate. Their influence in the relationship is assured, since by possessing power and legitimacy they form the dominant coalition.

5. Dependent stakeholders are characterised by a lack of power, but have urgent and legitimate claims. These stakeholders depend on others to carry out their will. Power in this relationship is not reciprocal and is advocated through the values of others.

6. Dangerous stakeholders possess urgency and power but not legitimacy and may be coercive or dangerous. The use of coercive power often accompanies illegitimate status.

7. Definitive stakeholders possess power legitimacy and urgency. Any stakeholder can become definitive by acquiring the missing attributes.

8. Non-stakeholders possess none o f the attributes and, thus, do not have any type of relationship with the group, organisation or project.“ (Boonstra 2006, pp. 40-41).

Boonstra then identifies the different stakeholders on the project, when they were evolved, which events triggered their involvement, and which meaning they gave the ERP system. The author shows that different stakeholders have different meanings, attitudes, and views, which dynamically change over time and which are not always disclosed. [Similar to the concept of technological frames described in this article.] Furthermore Boonstra underlined the importance of power as a major attribute for stakeholder salience. He also showed that Dominant Stakeholders can become Dormant Stakeholders, which activates other stakeholders to fill in that power gap.

For future research they briefly discuss two possible directions (1) linking stakeholder analysis to success/failure of projects and (2) exploring the role of the project manager.