Aritua, Bernard; Smith, Nigel J.; Bower, Denise: ; in: International Journal of Project Management, Article in Press, Corrected Proof.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.02.005

The meme of Complexity Theory is unstoppable in recent project management research. On the other hand it does make sense. Research such as this and, of course, common sense, indicate that the project’s context is a field better not left unmanaged. Since reality is quite complex and peoples‘ behaviour is anyway – a view like this increases the pre-existing complexity of projects management.

In this article Aritua et al. analyse the special complexity which presents itself in multi-project environments. I posted about complexity theory before and in more detail here.

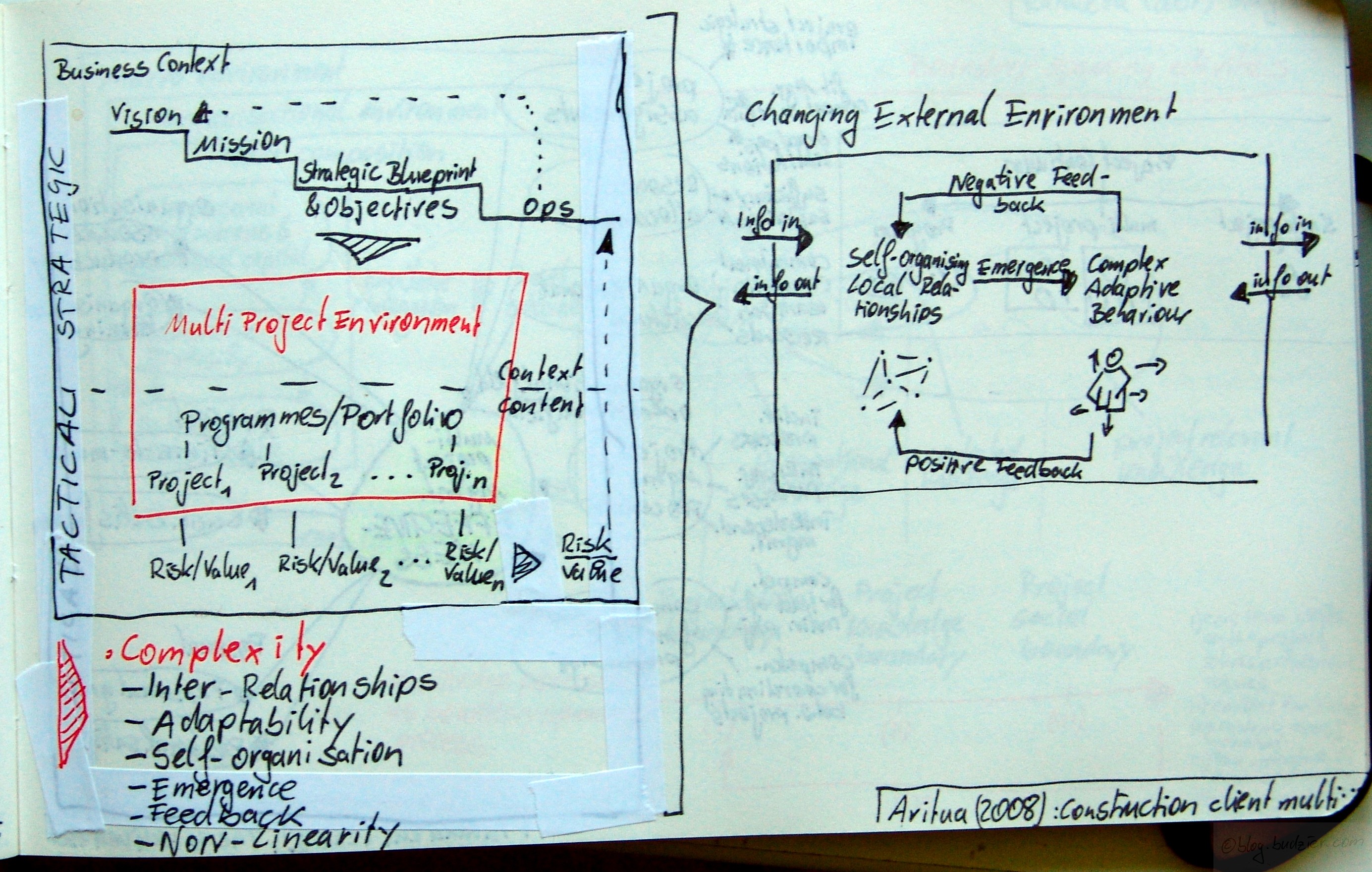

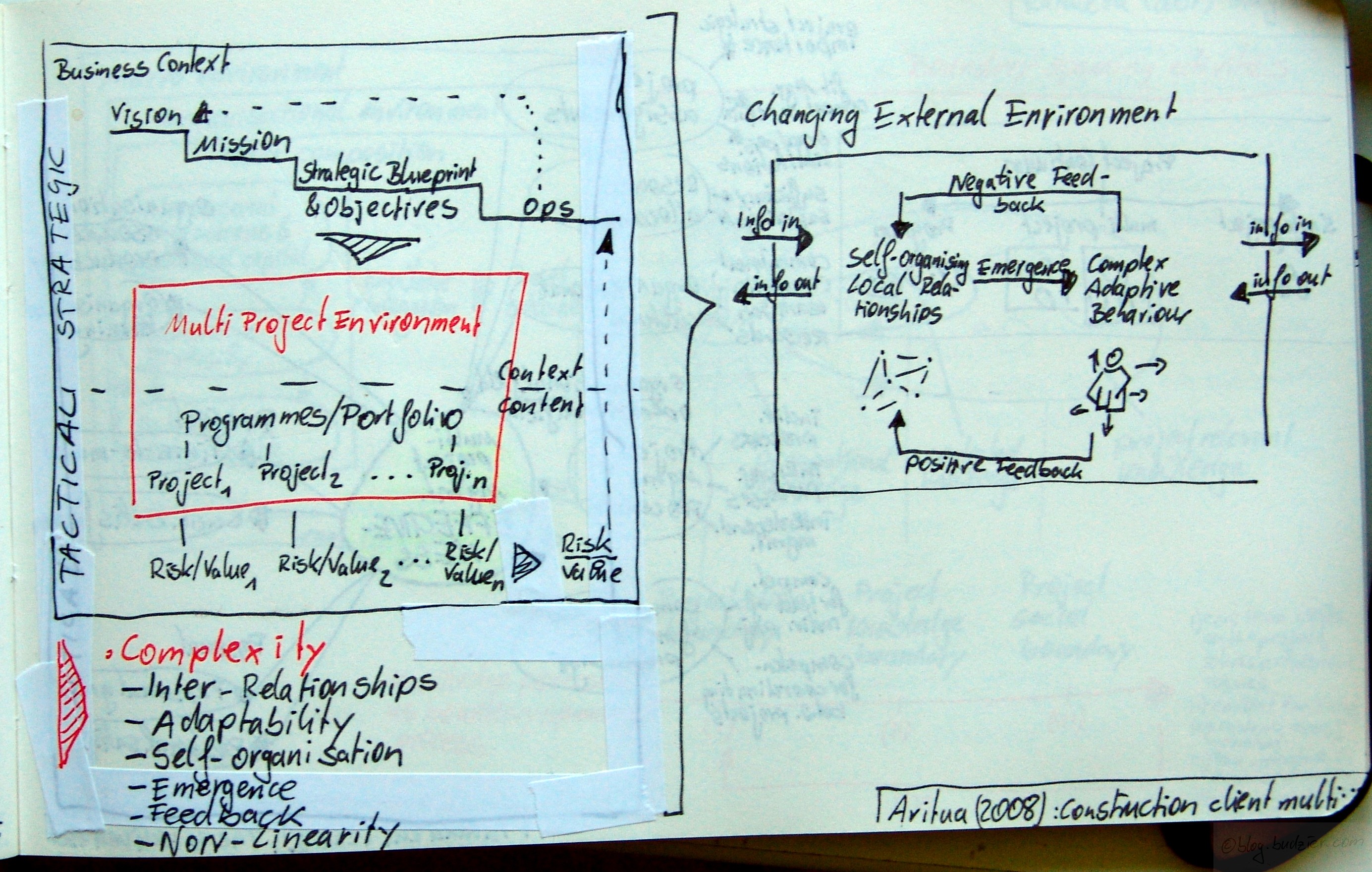

A quick recap. Complexity theory has 6 distinctive features, which make the outcomes of decisions, actions, and events increasingly unpredictable

- Inter-relationships

- Adaptability

- Self-organisation

- Emergence

- Feedback

- Non-linearity

Aritua et al. model the multi-project environment as being two-fold – (1) strategic environment and (2) tactical environment. The strategic environment builds the business context for the projects, programmes, or portfolio. The authors conceptualise the typical strategic cycle as consisting of vision – mission- strategic blueprint & objectives.

The tactical environment is the project portfolio/programme itself. Consisting of a couple of projects, it does provide a Risk:Value ratio for each project, which leads to an overall risk:value ration for the whole portfolio/programme, as such it feeds back into the strategic cycle in the business context environment.

In a second step the authors analyse the dynamics of such a system – what happens to a mulit-project portfolio if its external environment changes?

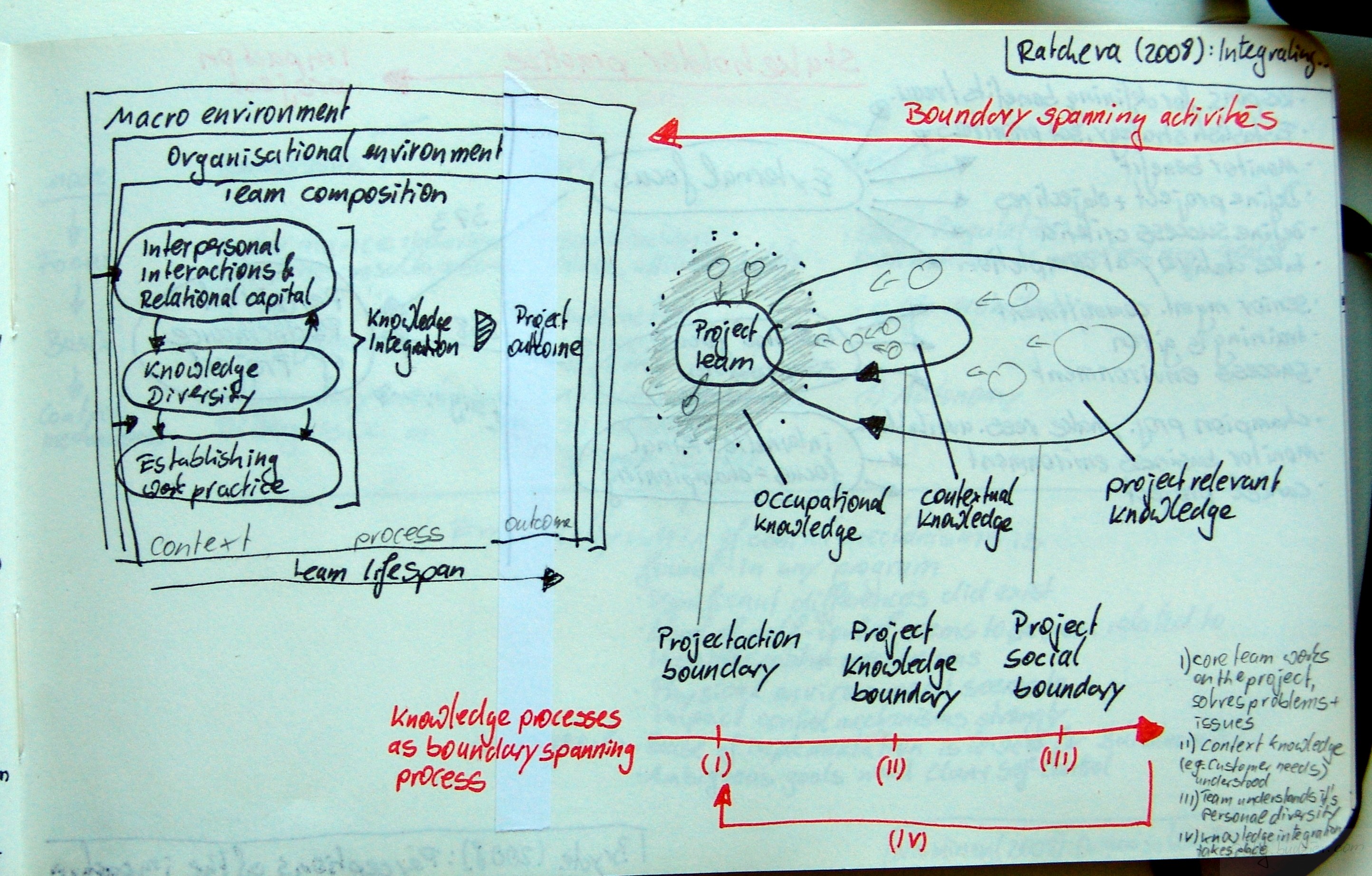

First of all, the boundary spanning activity in this conceptualisation is the information exchange with the environment. The information exchange into and out of the project portfolio triggers dynamics inside and between each project. Self-organising local relationships emerge into complex adaptive behaviour which feeds back, positively or negatively into the self-organising relationships. Huh?

Firstly, the project portfolio/programme is a complex system and therefore adapts itself when the environment changes. The one and only pre-requisite for this is, as the authors argue, that information and feedback freely flows inside, into, and out of the system.

Secondly, the self-organising relationships simply imply that individual components of the system affect each other and influence behaviour and actions. That is no project in a portfolio is independent from others. The authors cite the ant colony example, where ants make individual decision based on decisions by their closest neighbours. Thus complex interaction emerges.

Thirdly, self-organisation is the driving force behind creating stability in this open system. As the authors put it: „This aspect of the relationship between complexity theory and multi-project management would imply that programme managers and portfolio managers should not be bogged down with detail and should allow and enable competent project managers to act more creatively and on their own. This understanding also influences multi-project managers to seek a balance between trusting project managers and allowing them to concentrate on details on the one hand while seeking the necessary level of control and accountability.“

Fourthly, emergence is the effect that the group behaviour is more than the sum of behaviours of each individual project. Which implies, that risk and value can better be managed and balanced in a portfolio. On the flipside non-linearity shows that small changes in the system have unpredictable outcomes, which might be quite large. Thus management tools which don’t rely on non-linearity are needed. Moreover „it also emphasises the need for the multi-project management to react to the changing business environment to keep the strategic objectives at the fore while providing relative stability for the delivery of individual projects“.

So what shall the manager of a programme/portfolio do?

- Find a right balance between control and freedom for the individual projects (self-organisation)

- Enable information flow between the environment and the projects, as well as in between the projects (adaptability)

- Adapt strategic objectives, while stabilising project deliveries (feedback)

- Balance risk and value in the portfolio (emergence)

- Use non-linear management tools (non-linearity), such as AHP, Outranking, mental modelling & simulation

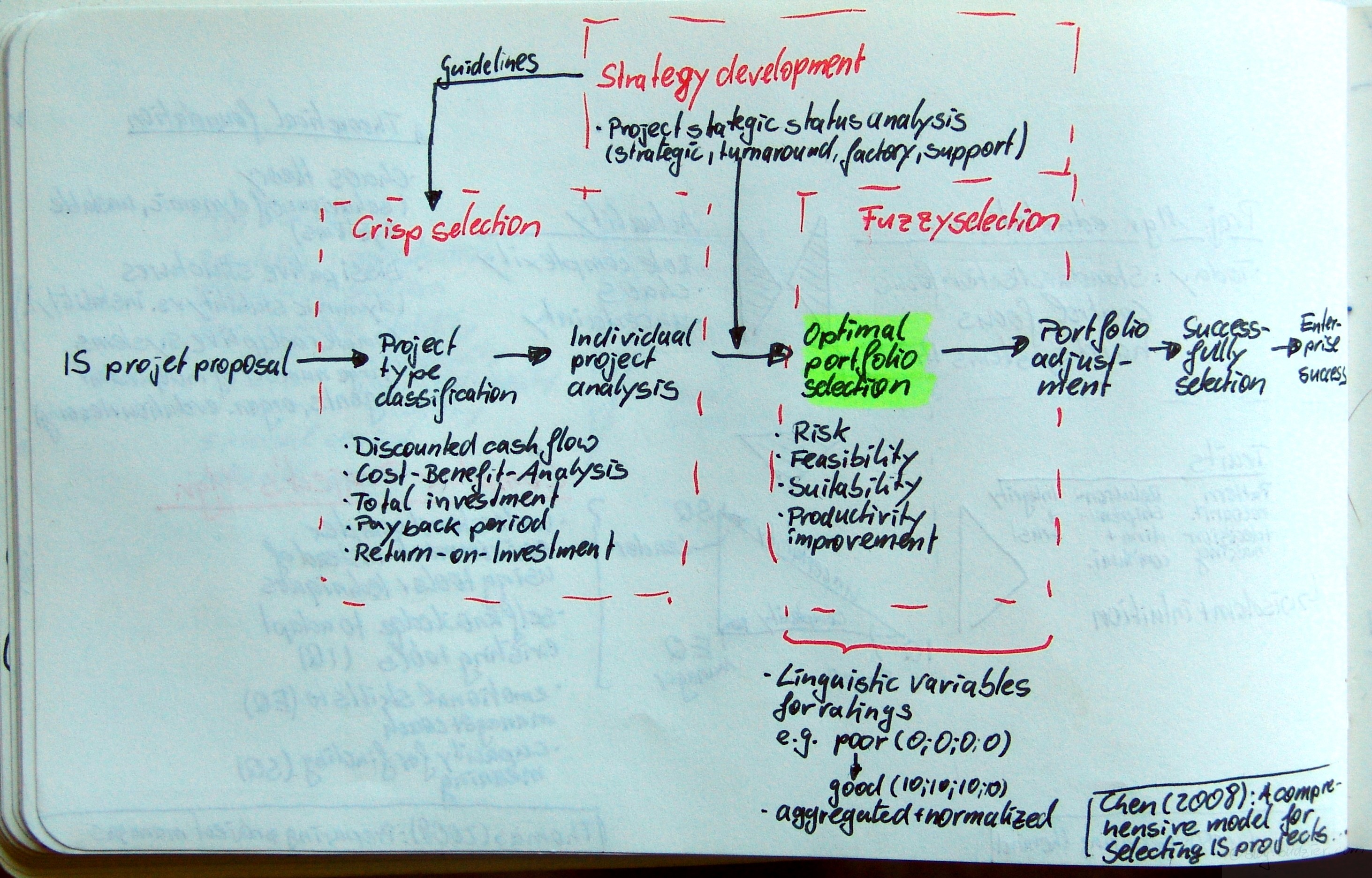

Chen, Chen-Tung; Cheng, Hui-Ling: A comprehensive model for selecting information system project under fuzzy environment; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press.doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.04.001Update: this article has been published in: International Journal of Project Management Vol. 27 (2009), No. 4, pp. 389399.Upfront management is an ever growing body of research and currently develops into it’s own profession. In this article Chen & Cheng propose a model for the optimal IT project portfolio selection. They outline a seven step process from the IT/IS/ITC project proposal to the enterprise success

Chen, Chen-Tung; Cheng, Hui-Ling: A comprehensive model for selecting information system project under fuzzy environment; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press.doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.04.001Update: this article has been published in: International Journal of Project Management Vol. 27 (2009), No. 4, pp. 389399.Upfront management is an ever growing body of research and currently develops into it’s own profession. In this article Chen & Cheng propose a model for the optimal IT project portfolio selection. They outline a seven step process from the IT/IS/ITC project proposal to the enterprise success