Bredillet, Christophe N.: Learning and acting in project situations through a meta-method (MAP) a case study – Contextual and situational approach for project management governance in management education; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 3, pp. 238-250.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.01.002

[This is a relatively complex post that follows – the article goes into epistemology quite deep (What is knowledge? How do we acquire it?) without much explanation given by the author. I tried to put together some explanatory background to make the rationale for the article more accessible. If you are just interested in the curriculum Bredillet proposes for learning project management on the job, skip these parts and jump right to the end of the post.]

In this article Bredillet outlines his meta-method used to teach project management. This method’s goal is to provide a framework in terms of processes and structure for learning in situ, namely on projects, programmes and alike. Bredillet argues that this method is best in accounting for complex, uncertain and ambiguous environments.

[Skip this part if you’re only interested in the actual application of the method.]

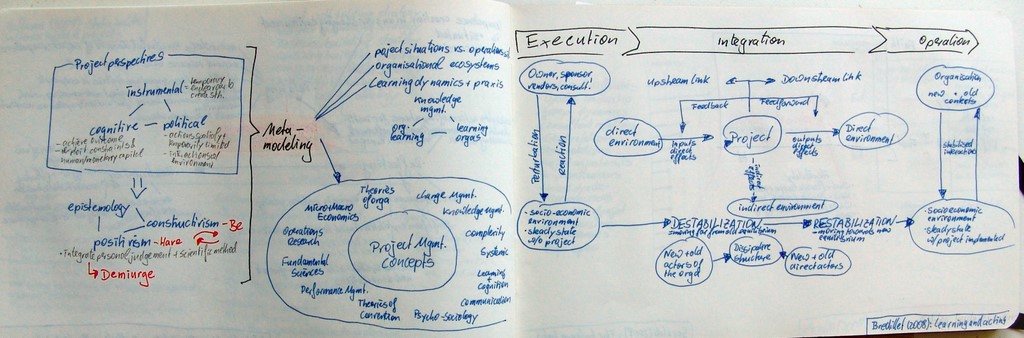

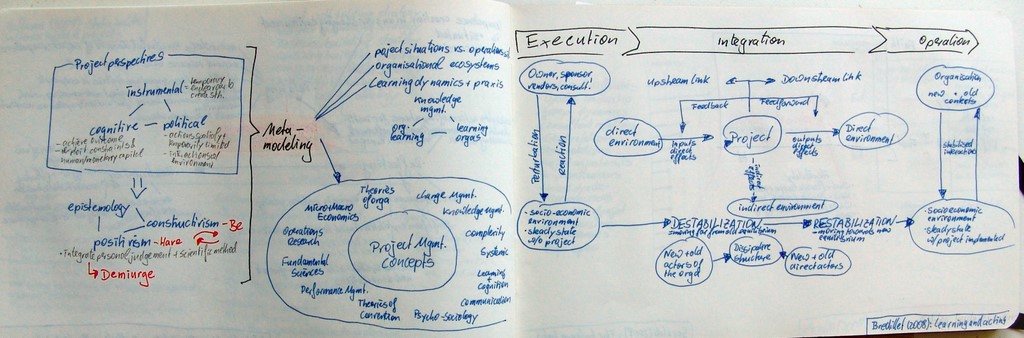

The authors starts with reviewing the three dominant project perspectives. a) Instrumental Perspective, which defines a project as a temporary endeavour to create something. b) Cognitive Perspective, which defines projects as exploitation of constraints and human/monetary capital in order to achieve an outcome. c) Political Perspective, which define projects as spatial actions which are temporarily limited, thus interacting with their environment. Bredillet argues that project management education does not reflect these perspectives according to their importance in the real world.

Bredillet argues that project management, knowledge creation and production (epistemology) have to integrate classical scientific aspects (Positivism) as well as fuzzy symbolisms (Constructivism). He says: „that the ‚demiurgic‘ characteristic of project management involves seeing this field as an open space, without ‚having‘ (Have) but rather with a raison d’être (Be), because of the construction of Real by the projects“ (p. 240).

Without any prior indulgence into epistemology (‚What is knowledge?‘ E. v. Glaserfeldt, Simon, Le Moigne etc.) this sentence is rather cryptic. What Bredillet wants to achieve is to unify the Positivist and Constructivist epistemology. Positivist epistemology can shortly be summarised to be our approach to understand the world quantitatively (= have = materialism, with only few degrees of freedom, e.g., best practices, OR, statistical methods). On the other hand Constructivist epistemology tries to understand the world with a qualitative focus (=be = immateriality, with many degrees of freedom, e.g., learning, knowledge management, change management). Bredillet summarises the constructivist epistemology citing Comte as „from Science comes Prevision, from Prevision comes Action“, and the positivist epistemology according to Le Moigne’s two hypothesis of reference – phenomenological („an existing and knowledgeable reality may be constructed by its observers who are then its constructors“) and teleological („knowledge is what gets us somewhere and that knowledge is constructed with an aim“).

Bredillet then argues that most research follows the positivist approach, valuing explicit over tacit knowledge, individual knowledge over team/organisational knowledge. To practically span the gap between Constructivism and Positivism Bredillet suggests to acknowledge tacit, explicit, team and individual knowledge as „distinct forms inseparable and mutually enabling“ (p. 240).

How to unify Constructivsm and Postivitsm in Learning of Project Management?

Practically he explores common concepts always from both views, from the positivist and the constructivist standpoint, for instance, Bredillet describes concepts of organisational learning using the single-loop model (Postivism) vs. double-loop model, and system dynamics theory (Constructivsm). Secondly, Bredillet stresses that learning and praxis are integrated, which is what the MAP method is all about:

„The MAP method provides structure and process for analysing, solving and governance of macro, meso, and micro projects. It is founded on the interaction between decision-makers, project team, and various stakeholders.“ (p. 240)

The three theoretical roots for the map method are (1) Praxeological epistemology, (2) N-Learning vs. S-Learning, (3) Theory of Convention. Thus the map method novelty is that it

- Recognises the co-evolution of actor and his/her environment,

- Enables integrated learning,

- Aims at generating a convention (rules of decision) to cope with the uncertainty and complexity in projects.

Ad (1): The basic premises of Praxeological epistemology [in Economics] taken from Block (1973):

- Human action can only be undertaken by individual actors

- Action necessarily requires a desired end and a technological plan

- Human action necessarily aims at improving the future

- Human action necessarily involves a choice among competing ends

- All means are necessarily scarce

- The actor must rank his alternative ends

- Choices continually change, both because of changed ends as well as means

- Labour power and nature logically predate, and were used to form, capital

- Technological knowledge is a factor of production

Ad (2): I don’t know whether n-Learning in this context stands for nano-Learning (constantly feeding mini chunks of learning on the job) or networked learning (network over the internet to learn from each other – blogs, wikis, mail etc.). Neither could I find a proper definition of S-Learning. Generally it seem to stand for supervised learning. Which can take place most commonly when training Neural Networks, and sometimes on the job.

Sorry – later on in the article Bredillet clarifies the lingo: N-Learning = Neoclassical Learning = Knowledge is cumulative; and S-Learning = Schumpeterian Learning = creative gales of destruction.

Ad (3): Convention Theory (as explained in this paper) debunks the notion that price is the best coordination mechanism in the economy. It states that there are collective coordination mechanisms and not only bilateral contracts, whose contingencies can be foreseen and written down.

Furthermore Convention Theory assumes Substantive Rationality of actors, radical uncertainty (no one knows the probability of future events), reflexive reasoning (‚I know that you know, that I know‘). Thus Convention Theory assumes Procedural Rationality of actors – actors judge by rational decision processes & rules and not by rational outcome of decisions.

These rules or convention for decision-making are sought by actors in the market. Moreover the theory states that

- Through conventions knowledge can be economised (e.g., mimicking the behaviour of other market participants);

- Conventions are a self-organising tools, relying on confidence in the convention

- Four types of coordination exist – market, industry, domestic, civic

[Start reading again if you’re just interested in the application of the method.]

In the article Bredillet then continues to discuss the elements of the MAP meta model:

- Project situations (entrepreneurial = generating a new position, advantage) vs. operations situations (= exploiting existing position, advantage)

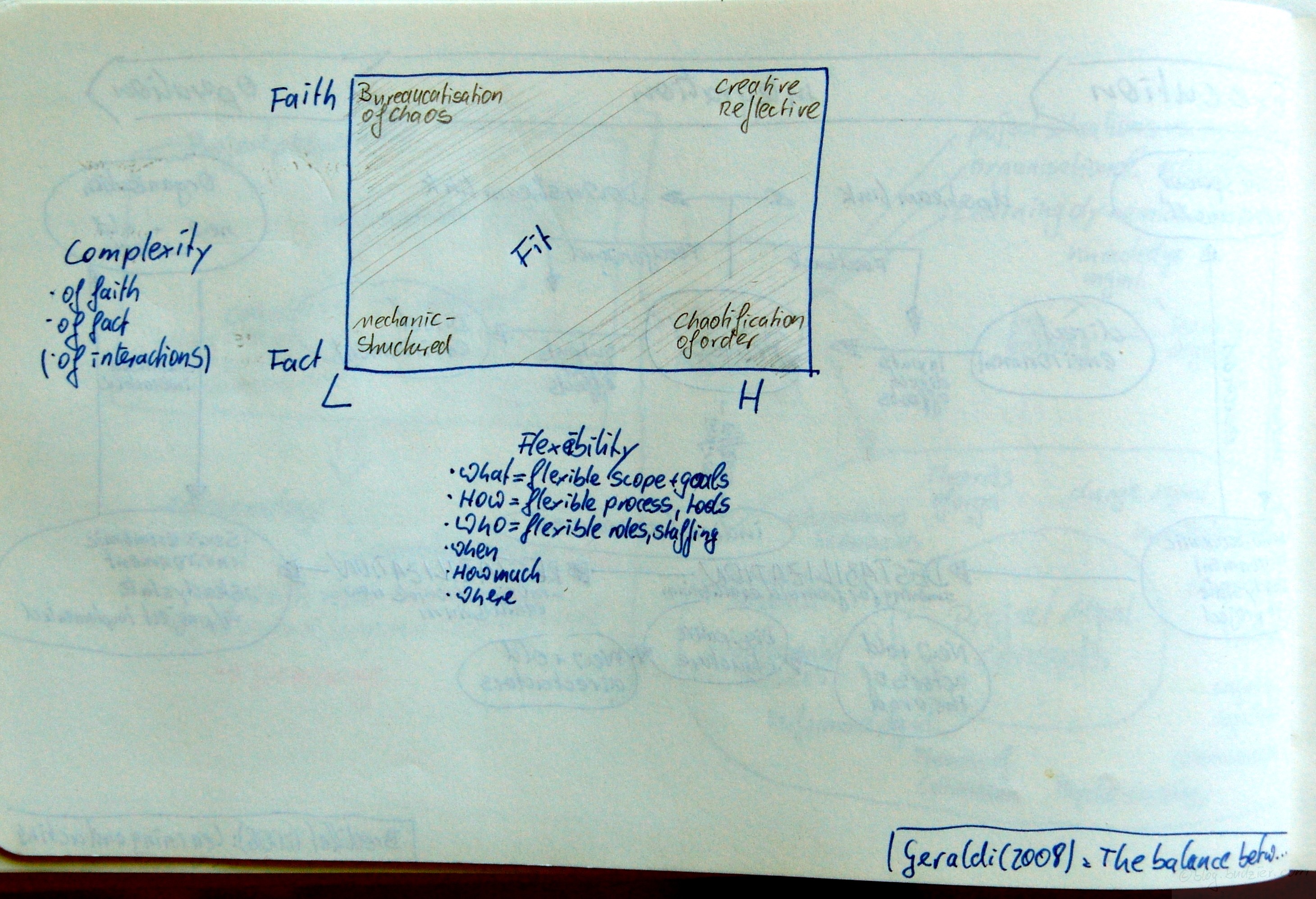

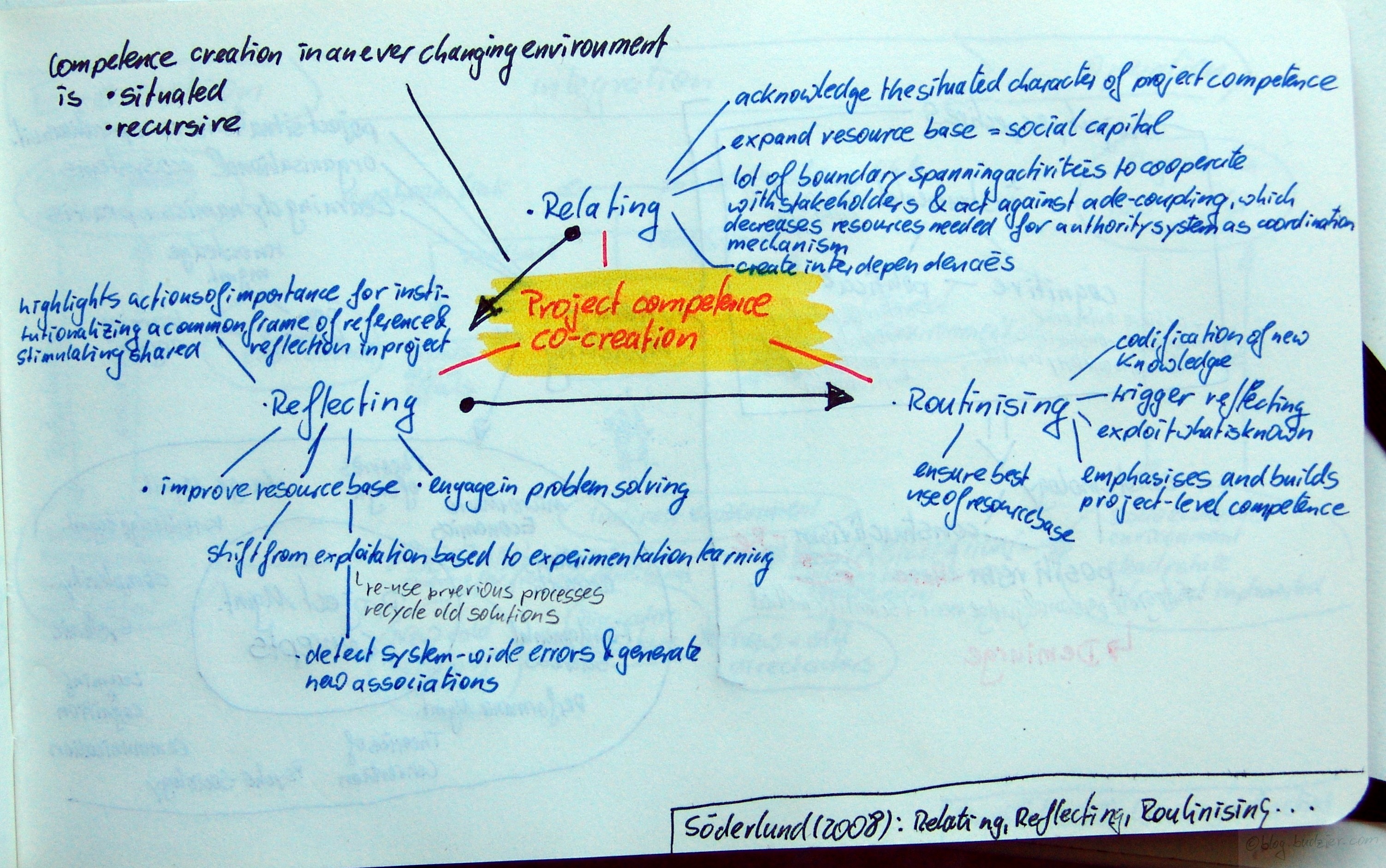

- Organisational ecosystem [as depicted on the right of my drawing]

- Learning dynamics and praxis, with the three cornerstones of knowledge management, organisational learning, and learning organisation

Thus learning in this complex, dynamic ecosystem with its different foci of learning should have three goals – (1) individual learning, e.g., acquire Prince 2/PMP methodology; (2) Team learning, e.g., acquire team conventions; and (3) organisational learning, e.g., acquire new competitive position.

The MAP model itself consists of the several project management theories and concepts [theories are depicted on the left side of my drawing], the concepts included are

- Strategic Management

- Risk Management

- Programme Management

- Prospective Analysis

- Projects vs. Operations

- Ecosystem project/context

- Trajectory of projects/lifecycles

- Knowledge Management – processes & objects; and individual & organisational level

- Systems thinking, dynamics

- Organisational design

- Systems engineering

- Modelling, object language, systems man model

- Applied sciences

- Organisational Learning (single loop vs. double loop, contingency theory, psychology, information theory, systems dynamics)

- Individual learning – dimensions (knowledge, attitudes, aptitudes) and processes (practical, emotional, cognitive)

- Group and team learning, communities of practice

- Leadership, competences, interpersonal aspects

- Performance management – BSC, intellectual capital, intangible assets, performance assessments, TQM, standardisation

The praxeology of these can be broken down into three steps, each with its own set of tools:

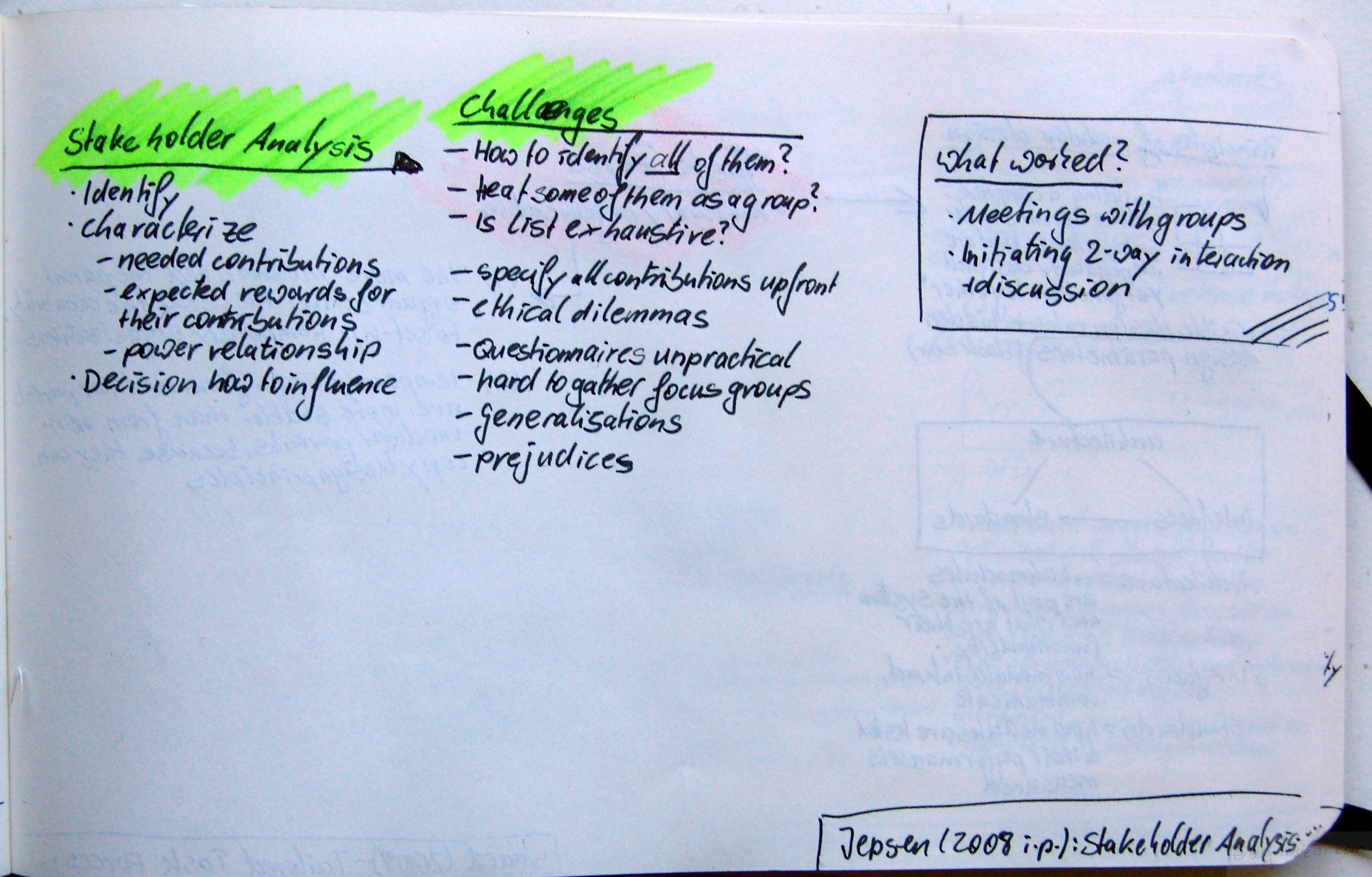

- System design – social system design (stakeholder analysis, interactions matrices), technical system design (logical framework, e.g., WBS matrix, and logical system tree)

- System analysis – risk analysis (technical/social risk analysis/mapping), scenario analysis (stakeholder variables & zones)

- System management – scheduling, organisation & planning, strategic control

As such, Bredillet describes the MAP method trajectory as

- Strategic choice with a) conception, b) formulation

- Tactical alternatives with a) alternatives analysis and evaluation, b) decision

- Realisation with a) implementation, b) reports and feedback, c) transition into operations, c) post-audit review

In praxis the learning takes part in form of simulations, where real life complex situations have to be solved using the various concepts, methods, tools, and techniques (quantitative and psycho-sociological) which are included in the MAP-method. To close the reflective learning loop at the end two meta-reports have to be written – use of methods and team work, and how learning is transferred to the workplace. Bredillet says that with this method his students developed case studies, scenario analysis, corporate strategy evaluation, and tools for strategic control.