Jani, Arpan: An experimental investigation of factors influencing perceived control over a failing IT project; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 7, pp. 726-732.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.06.004

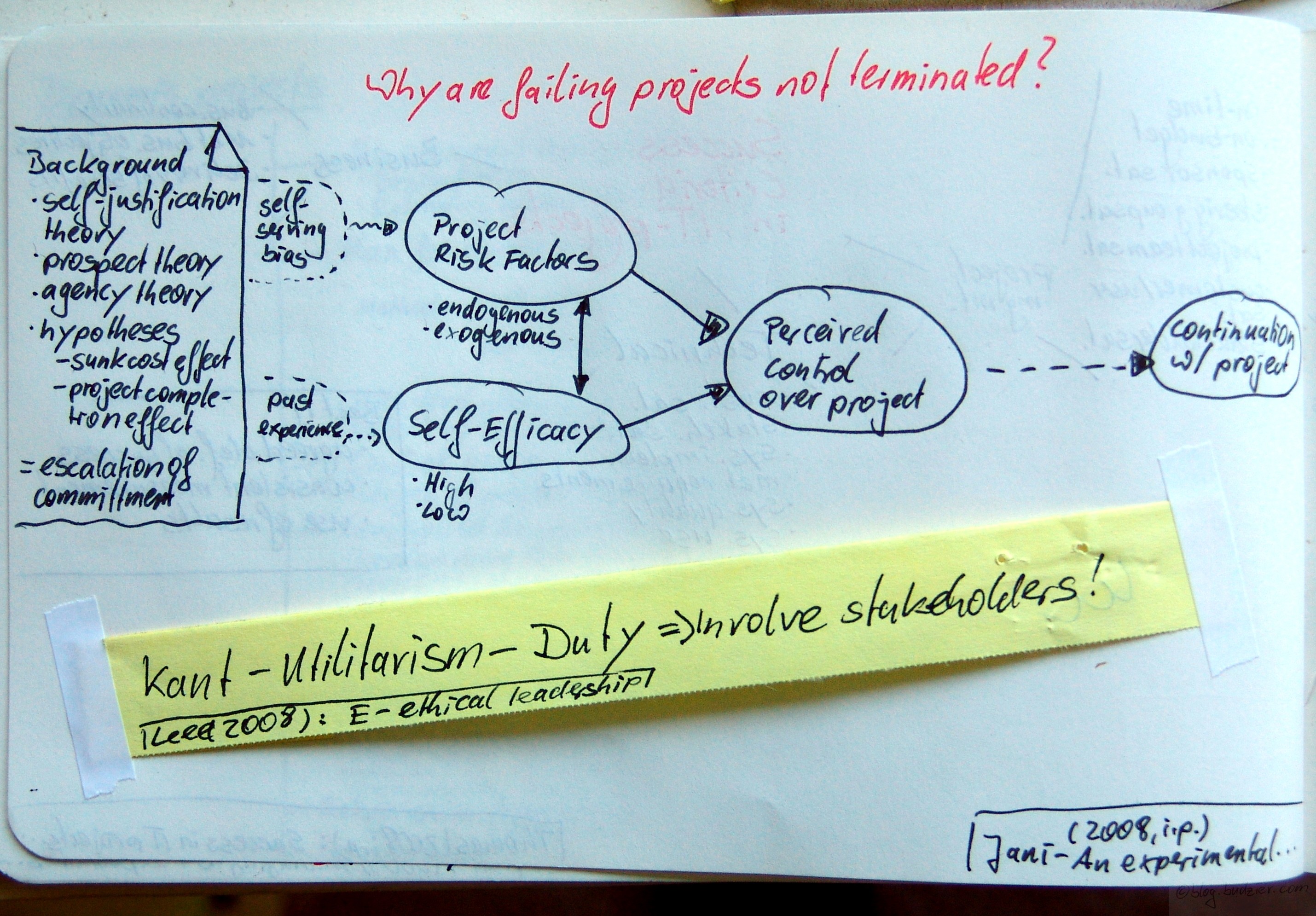

Jani wants to analyse why failing projects are not terminated, a spiralling development also called escalation of commitment (I posted about a case discussion of the escalation of commitment on the TAURUS project). Jani performed a computer simulated experiment to show the antecedents of a continuation decision.

He rooted the effect of escalating commitment on the self-justification theory, prospect theory, agency theory, and also on sunk cost effects & project completion effects.

Self-justification motivates behaviour to justify attitudes, actions, beliefs, and emotions. It is an effect of cognitive dissonance and an effective cognitive strategy to reduce the dissonance. An example for this behaviour is continuing with a bad behaviour, because stopping it would question the previous decision (= escalation of commitment).

Another example is bribery. People bribed with a large amount of money, tend not to change their attitudes, which were unfavourable otherwise there was nor reason to bribe them in the first place. But Festinger & Carlsmith reported that bribery with a very small amount of money, made people why they accepted the bribe although it had been that small, thus thinking that there must be something to it and changing their attitude altogether. Since I did it, and only got 1 Dollar is a very strong dissonance. Here is a nice summary about their classic experiments. Here is one of their original articles.

Jani argues that all these theoretical effects fall into two factors – (1) self-serving bias and (2) past experience. These influence the judgement on his two antecedents – (1) project risk factors (endogeneous and exogeneous) and (2) task specific self-efficacy. The latter is measured as a factor step high vs. low and describes how you perceive your capability to influence events that impact you (here is a great discussion of this topic by Bandura).

The two factors of project risk and task specific self-efficacy then influence the perceived control over the project which influences the continuation decision. Jani is able to show that task specific self-efficacy moderates the perceived project control. In fact he manipulated the project risks to simulate a failing projects, at no time participants had control over the outcome of their decisions. Still participants with a higher self-efficacy judged their perceived control significantly higher than participants with lower self-efficacy. This effect exists for engogenous and exogenous risk factors alike.

The bottom-line of this experiment is quite puzzling. A good project manager, who has a vast track record of completing past projects successfully, tends to underestimate the risks impacting the project. Jani recommends that even with great past experiences on delivering projects, third parties should always review project risks. Jani asks for caution using this advice since his experiment did not prove that joint evaluation corrects for this bias effectively.

Lee, Margaret E.: E-ethical leadership for virtual project teams; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press (2008).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.05.012

I quickly want to touch on this article, since the only interesting idea which stroke me was that Lee did draw a line from Kant to Utilitarism to the notion of Duty. She then concludes that it is our Kantesian, Utalitarian duty to involve stakeholders.