Willcocks, Leslie; Griffiths, Catherine: Predicting Risk of Failure in Large-Scale Information Technology Projects; in: Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 47 (1994), No. 2, pp. 205-228.

Willcocks & Griffiths analyse risk management practice. They find that wrong tools are used, especially statistical and finance tools which create a false accuracy and are insufficient to set risks in the broader context they belong to. Thus risk management focuses on valuation of economical impacts instead of actively managing the risks themselves.

The authors analyse 6 well known ITC projects Singapore’s TradeNet (electronic data interchange (EDI) for all aspects of the flow of goods), UK’s Department of Social Security automation, India’s CRISP project (automate information collection and processing in India’s Integrated Rural Development program), Videotext (and it’s historical predecessor Minitel in France, Prestel in UK, and BTX in Germany), London Stock Exchange’s Taurus (automate trading, paperless dealing and contracting of shares).

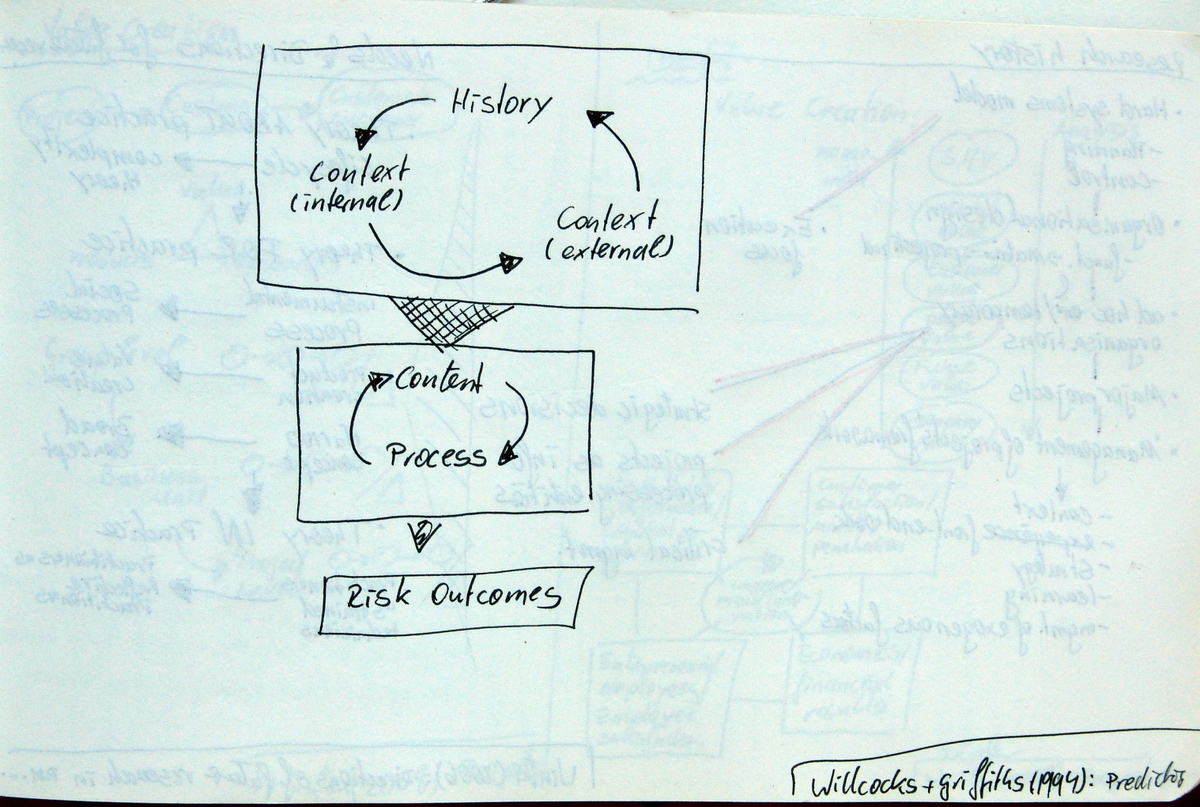

Willcocks & Griffiths present their framework how to predict risk of failure of a large scale IT project more accurately. They develop a 3 step risk management approach (1) history & context, (2) process, and (3) risk outcomes.

History includes previous successes/failures, relevant experience and organizational assets. It also includes internal context, which is defined by characteristics of the organisation (e.g. strategy, structure, reward systems, HR, management), changing stakeholder needs and objectives, employee relations context, and IT infrastructure and management. Furthermore the first step analyses the external context which includes level of government support, environmental pressures, newness/maturity of technology, maturity of consultants/suppliers, and the market demand.

The second step is the project itself as characterised by its processes and content. The risk associated with the project’s content are driven by size, complexity, definitional and technical uncertainty, and the number of units involved. The process risks are influenced by governance structures, project management and succession, management support, user commitment, project time span, team experience, and staffing stability.

Risk outcomes can be described by cost, time, and technical performance. Moreover they include stakeholder benefits, organisational/national impacts, user/market acceptance, and usage of the final ITC deliverable.