Oktober 23rd, 2008

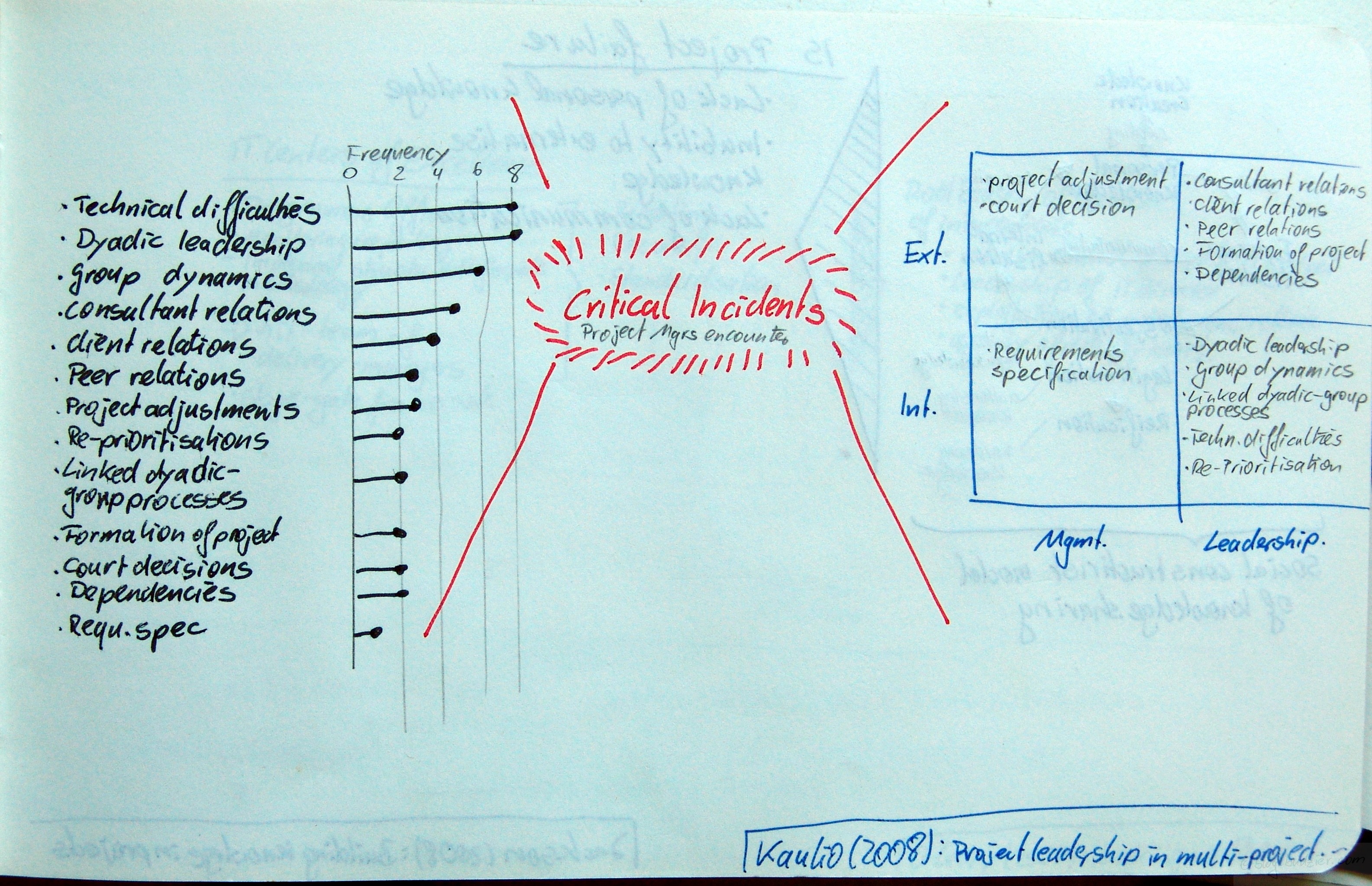

Kaulio, Matti A.: Project leadership in multi-project settings – Findings from a critical incident study; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 4, pp. 338-347.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.06.005

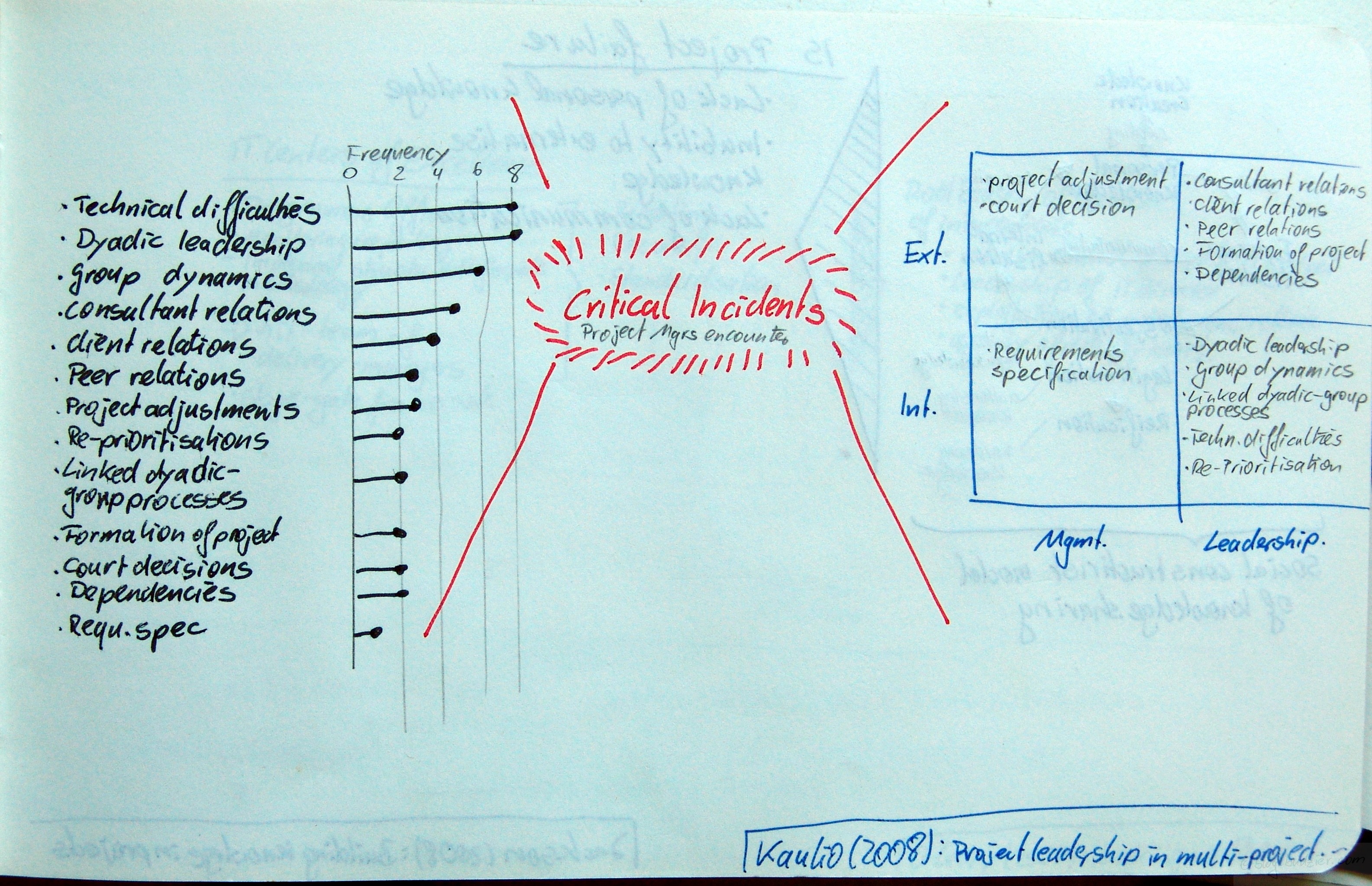

Kaulio asked project leaders, who operate in a multi-project environment about critical incidents in their last projects. The idea of critical incidents is, that as soon as a participant remembers the critical incident it must have some importance. Ideally it then is followed by a blueprint analysis followed by measuring the criticality is measured on each contact point. Kaulio focusses only on the elicitation of the critical incidents, without doing the triple-loop of the original research concept. The author shows the frequency of critical incidents happening:

- Technical difficulties

- Dyadic leadership

- Group dynamics

- Consultant relations

- Client relations

- Peer relations

- Project adjustments

- Re-prioritisations

- Liked dyadic-group processes

- Formation of project

- Court decisions

- Dependencies

- Requirements specification

Kaulio then maps these critical incidents according to the Locus of Control (internal vs. external) and whether they are a Management or a Leadership issue. Thus he argues most of the critical incidents can be tied back to internal project leadership:

| Locus of Control |

External |

- Project adjustment

- Court decision

|

- Consultant relations

- Client relations

- Peer relations

- Formation of project

- Dependencies

|

| Internal |

- Requirements specification

|

- Dyadic leadership

- Group dynamics

- Linked dyadic-group processes

- Technical difficulties

- Re-prioritisation

|

|

|

Management |

Leadership |

|

|

Focus |

Posted in Conflicts, Critical Incident Technique, Failed Projects, IT Project, Leadership, Multi-project management | 3 Comments »

Oktober 23rd, 2008

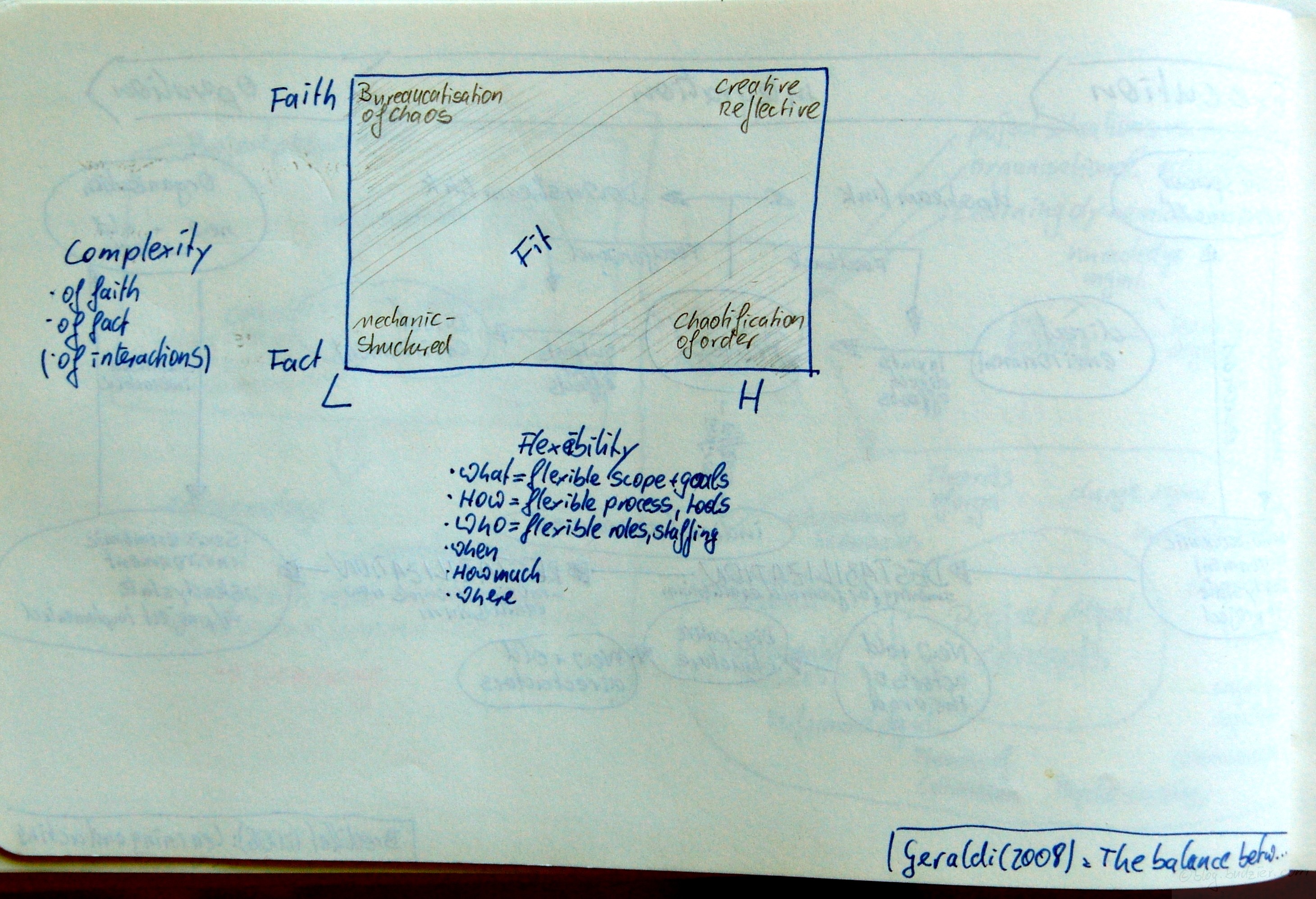

Geraldi, Joana G.: The balance between order and chaos in multi-project firms – A conceptual model; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 4, pp. 348-356.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.08.013

Geraldi takes a deeper look into multi-project settings at the ‚Edge of Chaos‘. Geraldi describes the Edge of Chaos as that fine line between chaos and order. Wikipedia (I know I shouldn’t cite it) has something else to say about the Edge of Chaos:

In the sciences in general, the phrase has come to refer to a metaphor that some physical, biological, economic and social systems operate in a region between order and either complete randomness or chaos, where the complexity is maximal. The generality and significance of the idea, however, has since been called into question by Melanie Mitchell and others. The phrase has also been borrowed by the business community and is sometimes used inappropriately and in contexts that are far from the original scope of the meaning of the term.

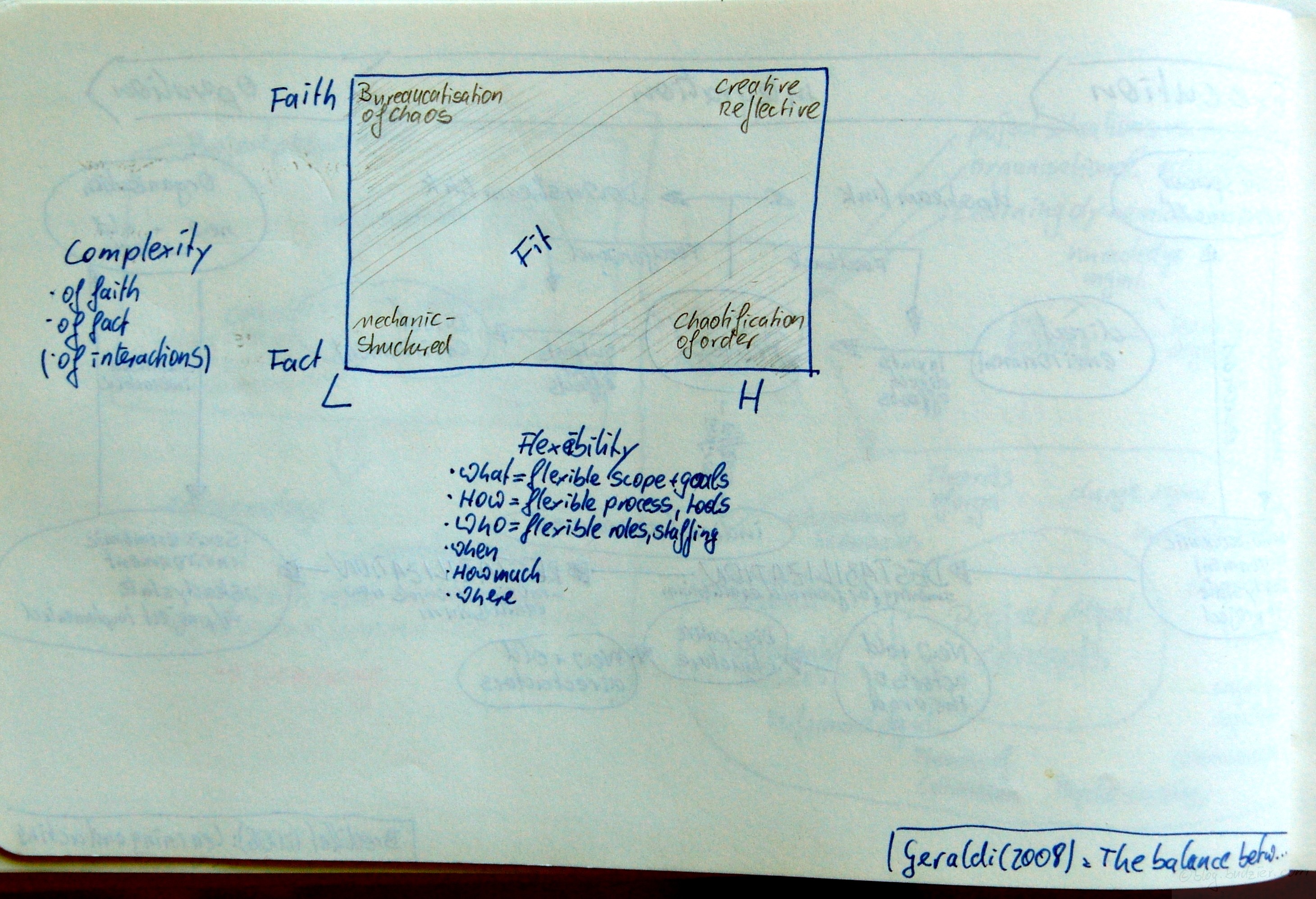

Geraldi defines the Edge of Chaos as a match between complexity and flexibility. Complexity can either be located within faith or facts. Flexibility, on the other hand, is either high or low, whilst it is measured along the dimensions of scope + goals, processes + tools, and roles + staffing. Geraldi argues that only two of these archetypes represent a fit (highlighted below):

| Complexity |

Faith |

Bureaucratisation of Chaos |

Creative Reflective |

| Fact |

Mechanic-Structured |

Chaotification of order |

|

|

Low |

High |

|

|

Flexibility |

Posted in Complexity, Culture, Hard and soft projects, Multi-project management, Program Management, Uncertainty management | No Comments »

Oktober 21st, 2008

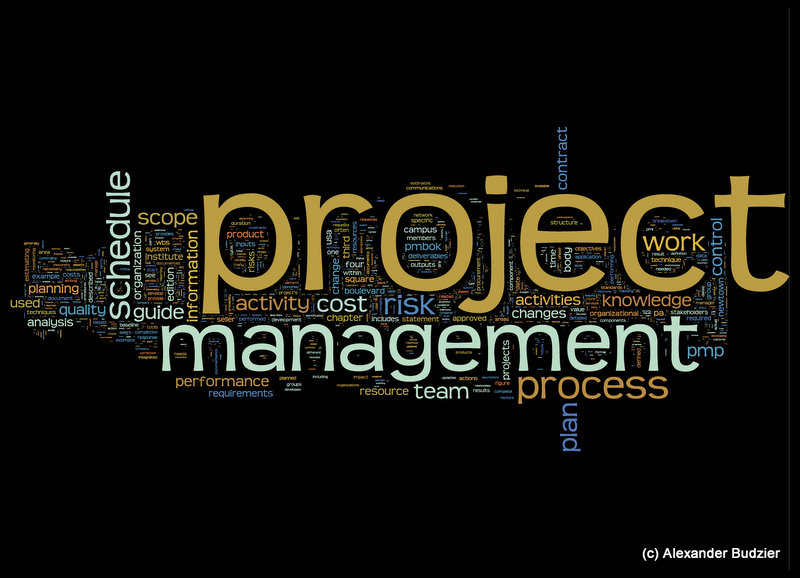

Today I woke up very early and created these beautiful pictures summarising all keywords from the last 5 years in the International Journal of Project Management and the Journal of Project Management.

In my lunch break another thought struck me – you need something on that bare wall you have here. From there on it was a short step to run the PMI’s PMBOK Guide 3rd Ed. through wordle.net and after a lot of tweaking, it created some beautiful posters, reminding me what the PMP is all about. I use Lulu.com to print the poster on demand – I am quite satisfied with Lulu the largest poster measuring 23″ x 36″ (61cm x 91 cm) comes for just $39.95, excluding shipping.

The posters can be ordered at my Lulu Store.

And here are all of the designs I put online:

These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Licence.

Posted in Admin, Case Study, Failed Projects, Methodology, Tag Cloud | 95 Comments »

Oktober 21st, 2008

One of my other interests is data visualisation. When I started my work on this project, I wanted to get a quick overlook of what Project Management Research really is about. After I collected all author-given keywords from all articles in the International Journal of Project Management and the Journal of Project Management of the last 5 years (2003 and onwards) I created these Tag Clouds.This morning I stumbled across about a blog entry on information aestehetics written by Martin Wattenberg, the group manager of IBM Visual Communication lab. After some more random klicks I landed on Wordle.net, Wordle is the aestethically more pleasing cousin of the cloud tag and I started redoing my earlier excercise to generate some sleek new summaries:

International Journal of Project Management 2003-2008

Journal of Project Management 2003-2007

Keywords published in International Journal of Project Management and Journal of Project Management 2003-2008

These are the links to the original graphics in the Wordle gallery – these are licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA:

Posted in Literature Review, Tag Cloud | 4 Comments »

Oktober 20th, 2008

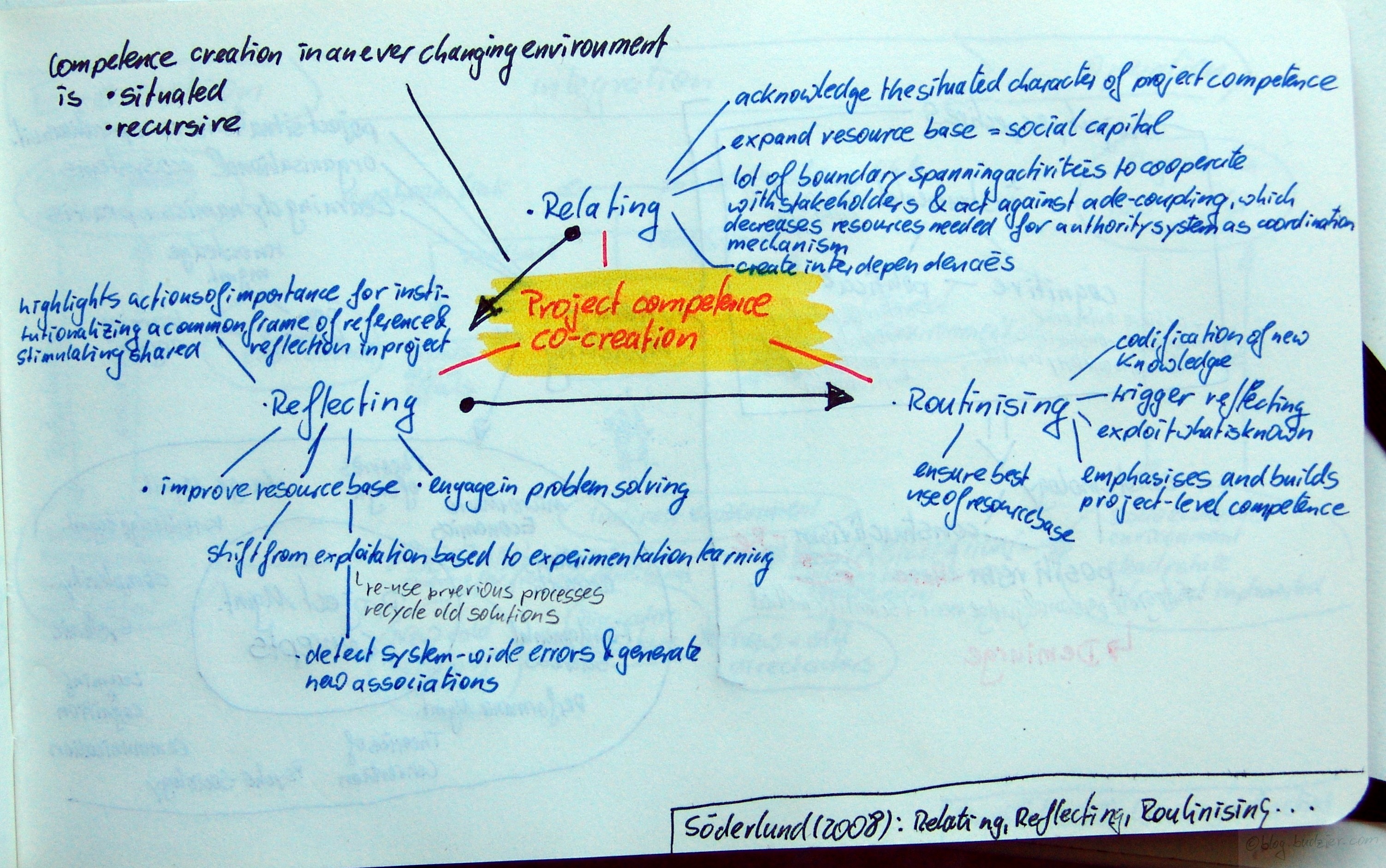

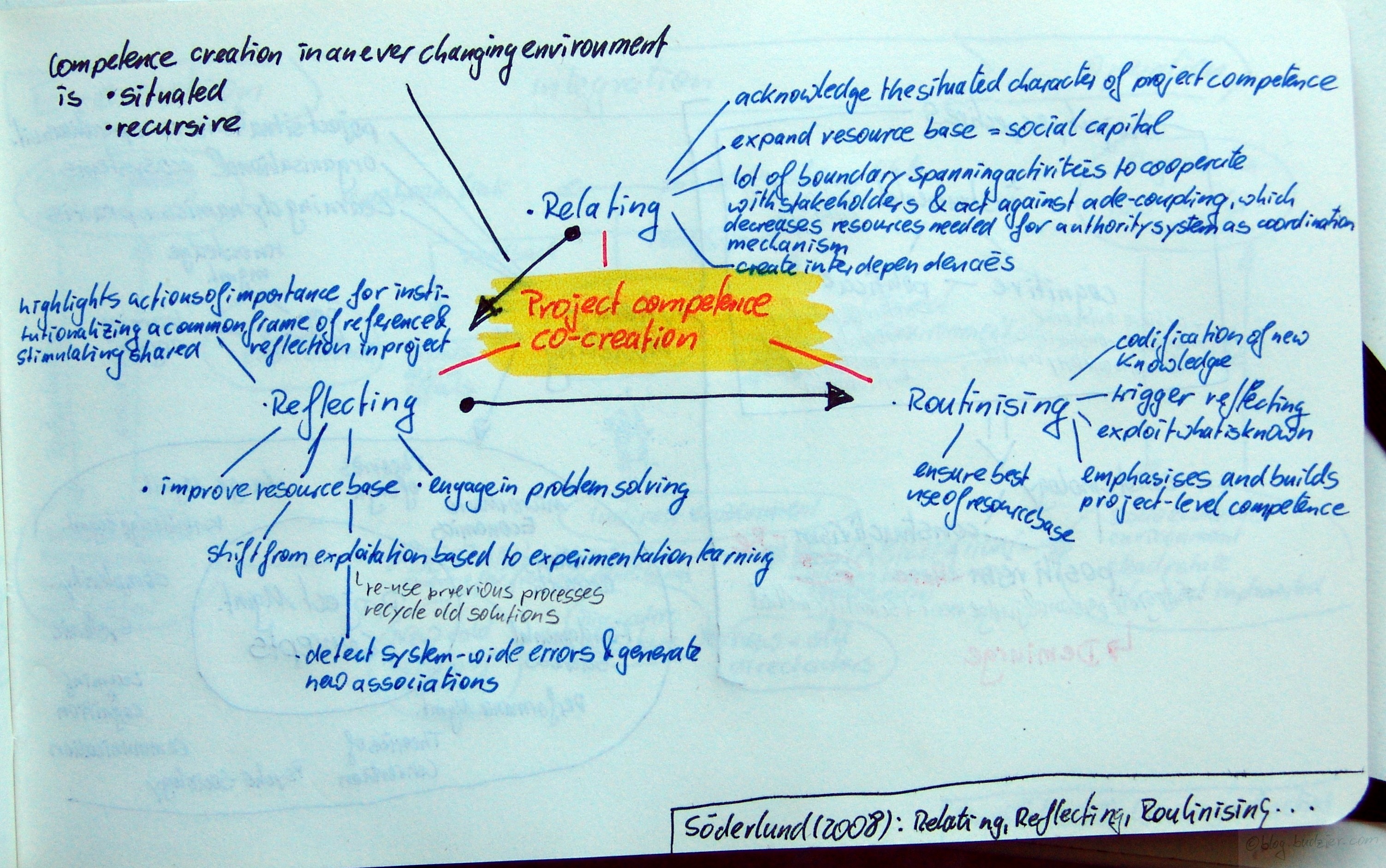

Söderlund, Jonas; Vaagaasar, Anne Live; Andersen, Erling S.: Relating, reflecting and routinizing – Developing project competence in cooperation with others; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 5, pp. 517-526.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.06.002

Söderlund et al. explore the question – How do organisations build project management capabilities? They analyse a focal project to show how the specific competence, project management, is build in an ever changing environment. As such comptence creation is situated and recursive.

The authors use a process view to explain the capabilities building. The process is three-fold – (1) Relating, (2) Reflecting, and (3) Routinising.

First step – Relating to expand the resource base, in this step the organisation

- Acknowledges the situated character of project competence

- Expands the resource base, which builds social capital

- Engages in boundary spanning activites to cooperate with stakeholders and act against de-coupling, which decreases the overall resources needed for the authority system as coordination mechanism

- Creates interdependencies

Second step – Reflecting to improve use of resource base, in this step the organisation highlights actions of importance for institutionalising a common frame of reference and stimulating shared reflection in the project. As such it:

- Improves the resource base

- Engages in problem solving

- Shifts from exploitation based to experimentation learning, which re-uses previous processes, and recycles old solutions

- Detects system-wide errors & generates new associations

Third step – Routinising to secure resource base and improve relational activity, in this step the organisation tries to ensure the best use of its resource base. Therefore it

- Codifies new knowledge

- Triggers reflecting

- Exploits what is known

- Emphasises and builds project-level comptence

Posted in Case Study, Complexity, Megaprojects, Organisational capabilities | 1 Comment »

Oktober 20th, 2008

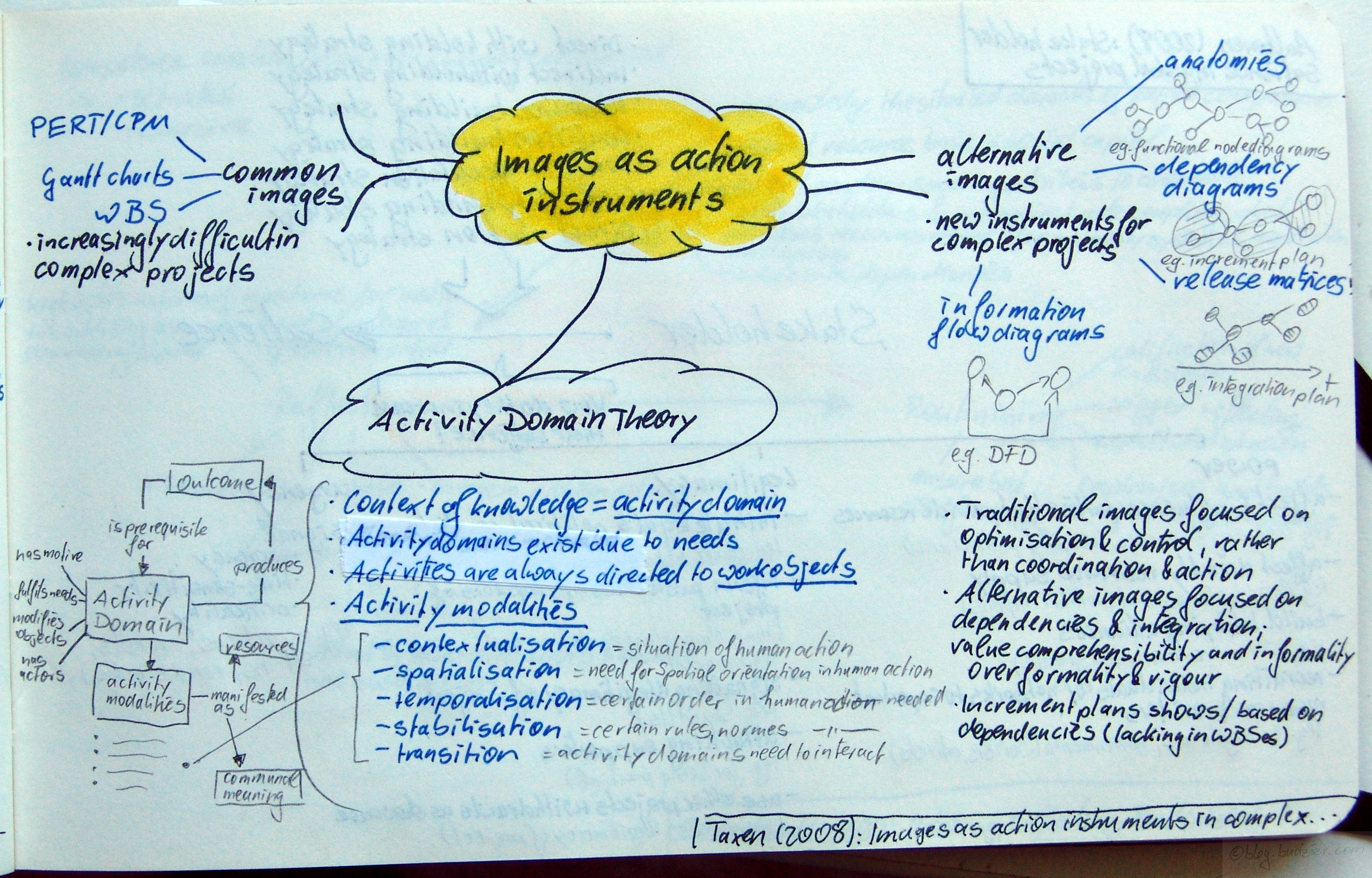

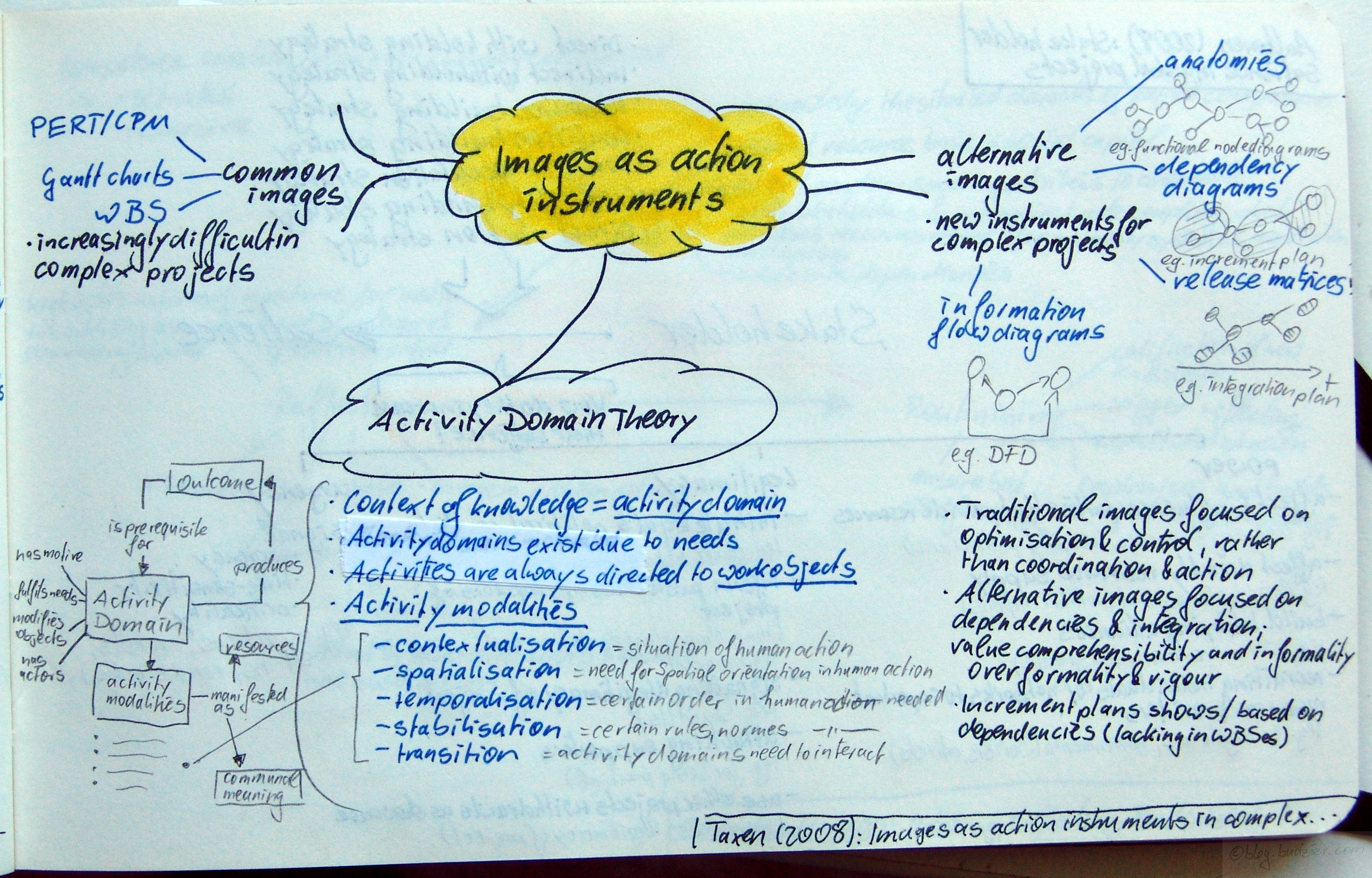

Taxén, Lars; Lilliesköld, Joakim: Images as action instruments in complex projects; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 5, pp. 527-536.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.05.009

Images are quite powerful. I hate motivational posters which a distant corporate HQ decorates every meeting room with, but I once saw the department strategy visualised by these folks, they include all employees and the group dynamic is unbelievable. Later on they cleaned the images, blew them up, and posted them around the company – of course, meaningless for an outsider but a powerful reminder for everyone who took part.

Taxén & Lilliesköld analyse the images typically used in project management. They find that these common images, such as PERT/CPM, Gantt charts, or WBS are increasingly difficult to use in complex projects, in this case the authors look into a large-scale IT project.

Based on Activity Domain Theory they develop alternative images better suited for complex projects. Activity Domain Theory, however, underlines that all tasks on a project (= each activity domain) have a motive, fulfils needs, modifies objects, and has actors. Outcomes are produced by activity domains and are at the same time prerequisites for activity domains. Activity domains have activity modalities, which can be either manifested as resources or as communal meaning. These activity modalities are

- Contextualisation = situation of human action

- Spatialisation = need for spatial orientation in human action

- Temporalisation = need for certain order in human action

- Stabilisation = need for certain rules and norms in human action

- Transition = need for interaction between activity domains

Useful images, the authors argue, need to fulfil these needs while being situated in the context of the activity. Traditional images focus on optimisation and control, rather than on coordination and action. Thus alternate images need to focus on dependencies and integration; on value comprehensibility and informality over formality and rigour.

Alternative images suited for complex project management are

- Anatomies – showing modules, work packages and their dependencies of the finished product, e.g., functional node diagrams

- Dependency diagrams – showing the incremental assembly of the product over a couple of releases, e.g. increment plan based on dependencies (a feature WBS lack)

- Release matrices – showing the flow of releases, how they fit together, and when which functionality becomes available, e.g., integration plan

- Information flow diagrams – showing the interfaces between modules, e.g. DFD

Posted in Case Study, Communication, Complexity, Critical Chain, IT Project, Leadership, Methodology, Planning, Project Organisation, Tools, Uncertainty management | 3 Comments »

Oktober 20th, 2008

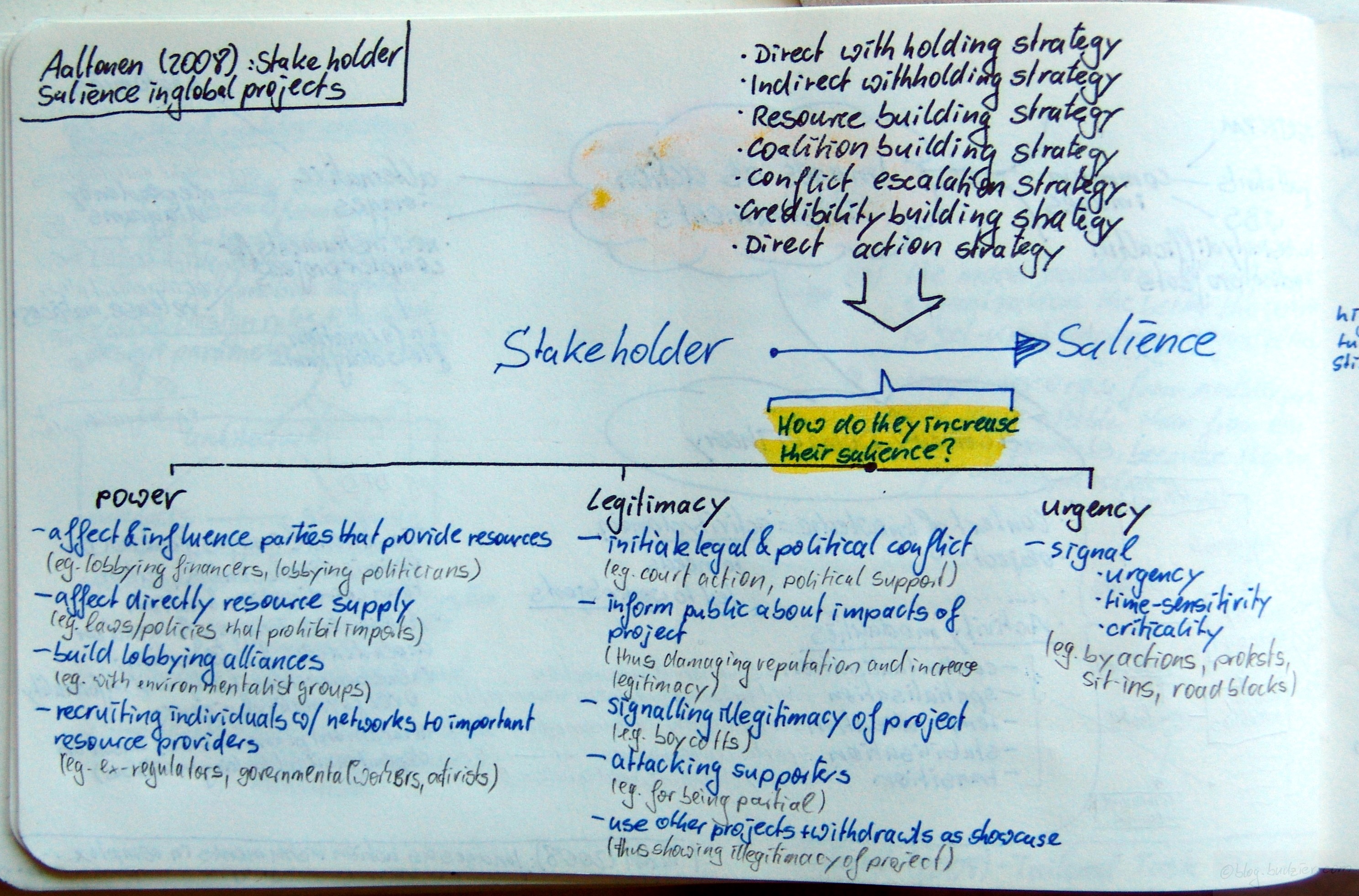

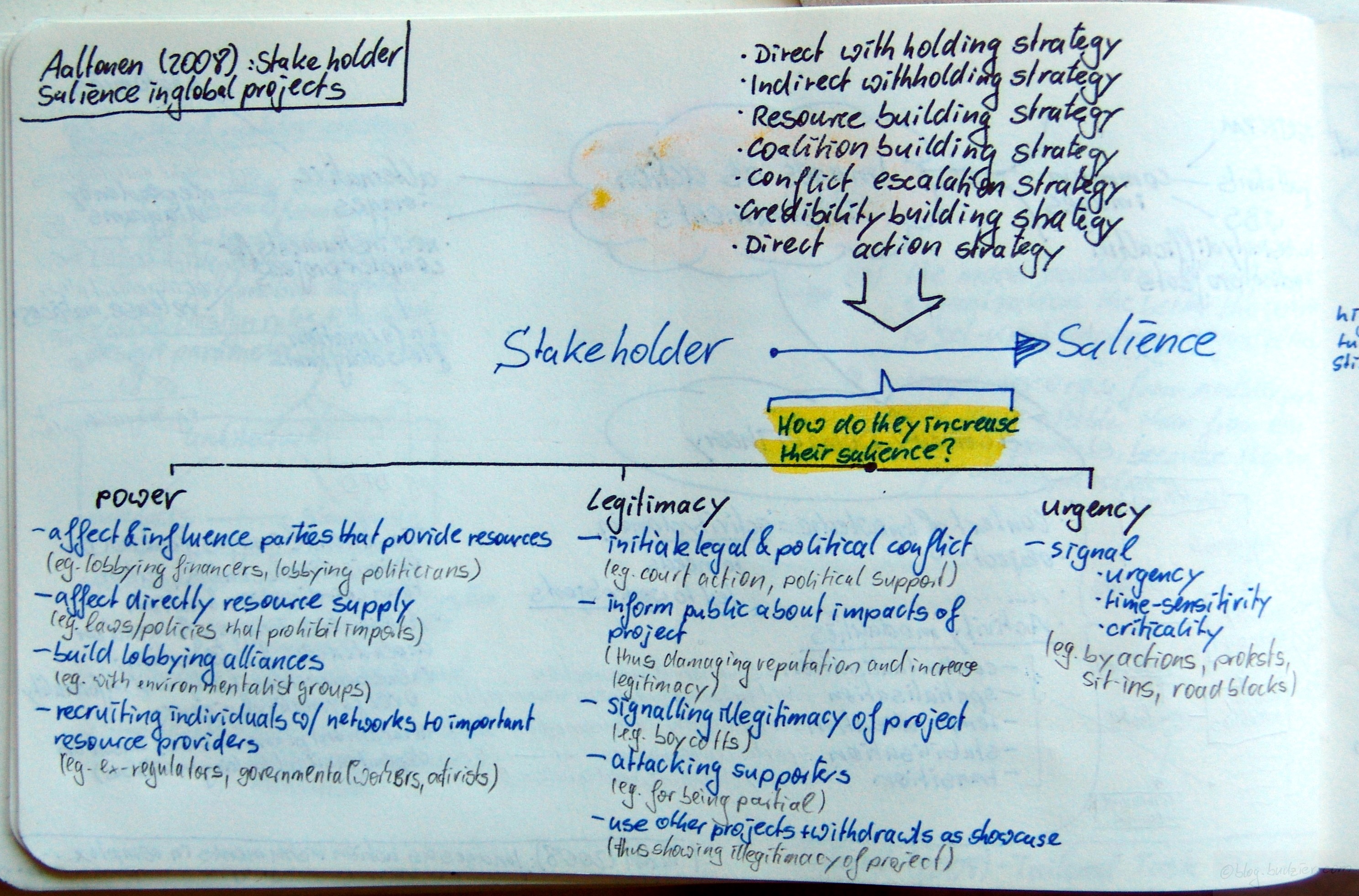

Aaltonen, Kirsi; Jaako, Kujala; Tuomas, Oijala: Stakeholder salience in global projects; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 5, pp. 509-516.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.05.004

In their 1997 article, Mitchell et al. define stakeholder salience as „the degree to which managers give priority to competing stakeholder claims“. Furthermore, Mitchell at al. describe how the salience of a stakeholder is defined by three characteristics – (1) the stakeholder’s power to influence the firm, (2) the legitimacy of the stakeholder’s relationship with the firm, and (3) the urgency of the stakeholder’s claim on the firm.

Aaltonen et al. use the case study of a construction project of a paper-mill in South America to outline what strategies Stakeholders use to influence their salience. In line with typical case studies of construction projects Aaltonen’s stakeholders are environmentalist groups trying to influence the project. [I personally think based on my experience what Aaltonen et al. describe is also true for all sorts of projects, just if I think back to my organisational change and IT projects where we had workers‘ unions and councils as equally hard to manage stakeholders.] The authors observed a couple of strategies used:

- Direct/indirect withholding strategy

- Resource building strategy

- Coalition building strategy

- Conflict escalation strategy

- Credibility building strategy

- Direct action strategy

As per Mitchell’s definition these strategies aim to increase influencing power, legitimacy, and/or urgency. The tactics used to increase power were

- Affect & influence parties, that provide resources, e.g., lobbying financiers and politicians

- Affect the resource supply directy, e.g., laws and policies that prohibit imports

- Build lobbying alliances, e.g., between environmentalist groups and unions

- Recruit individuals with networks to important resource providers, e.g., ex-regulators, governmental workers, activists

The tactics used to increase legitimacy were

- Initiate legal and political conflict, e.g., court action, political support

- Inform the public about impacts of the project, thus damaging reputation of the project and increasing legitimacy

- Signal illegitimacy of project, e.g., boycotts, counter impact studies

- Attack supporters, e.g., showing them being partial, exposing lobbyists

- Use other projects as showcases, e.g., using abandoned projects and withdrawls to show the illigitimacy of the project

The tactic used to increase urgency was signalling urgency, time-sensitivity, and criticality of decisions, e.g., by staging direct actions, protests, sit-ins, road blocks.

Posted in Case Study, Conflicts, Failed Projects, Stakeholder Management | 3 Comments »

Oktober 20th, 2008

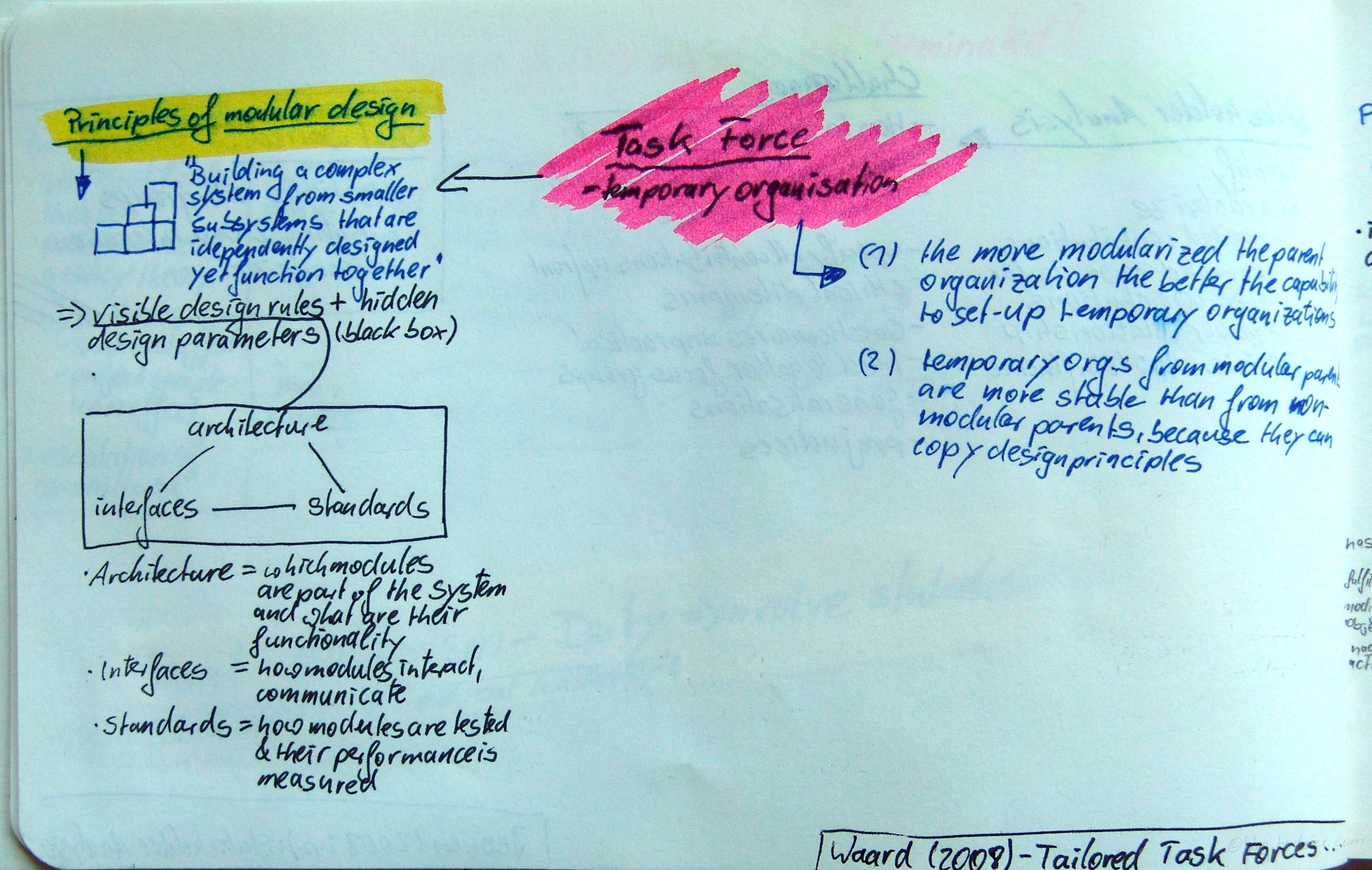

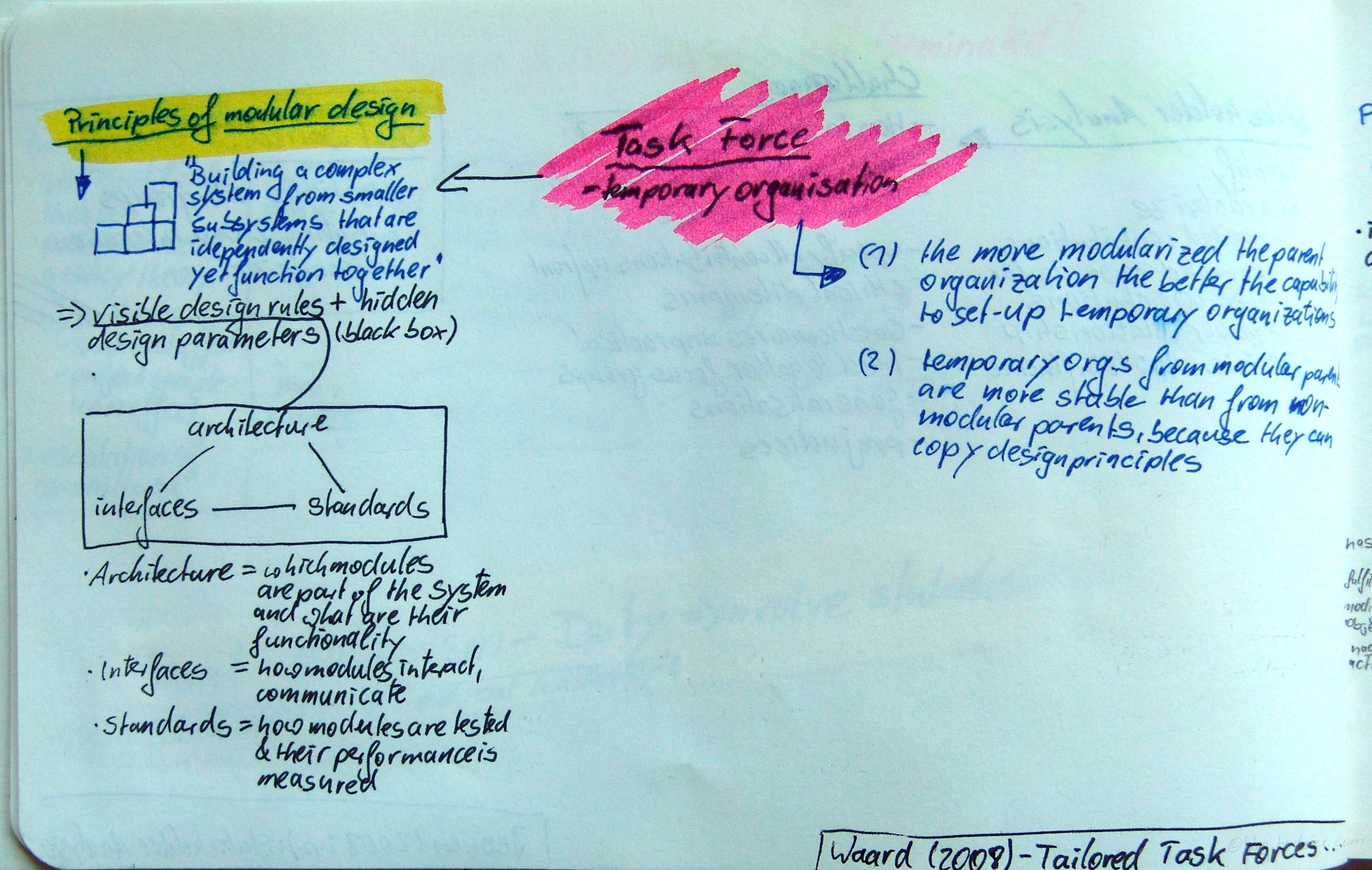

Waard, Erik J. de; Kramer, Eric-Hans: Tailored task forces – Temporary organizations and modularity; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 5, pp. 537-546.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.05.007

As a colleague once put it: Complex projects should be organised like terrorist organisations – Autonomous cells of highly motivated individuals.

Waard & Kramer do not analyse projects but it’s fast paced and short lived cousin – the task force. The task force is THE blueprint for an temporary organisation. The authors found that the more modularised the parent company is, the easier it is to set-up a task force/temporary organisations. Waard & Kramer also found that the temporary organisations are more stable if set-up by modular parent companies. They explain this with copying readily available organisational design principles and using well excercised behaviours to manage these units.

The more interesting second part of the article describes how a company can best set-up task forces. Waard & Kramer draw their analogy from Modular Design.

„Building a complex system from smaller subsystems that are independently designed yet function together“

The core of modular design is to establish visible design rules and hidden design parameters. The authors describe that rules need to be in place for (1) architecture, (2) interfaces, and (3) standards. The remaining design decisions is left in the hands of the task force, which is run like a black box.

In this case Architecture defines which modules are part of the system and what each modules functionality is. Interface definition lays out how these modules interact and communication. Lastly, the Standards define how modules are tested and how their performance is measured.

Posted in Actuality Research, Boundary, Communication, Complexity, Control, Culture, Decision Making, Organisation, Organisational capabilities, Project Strategy, Temporary organisation, Theory | 2 Comments »

Oktober 20th, 2008

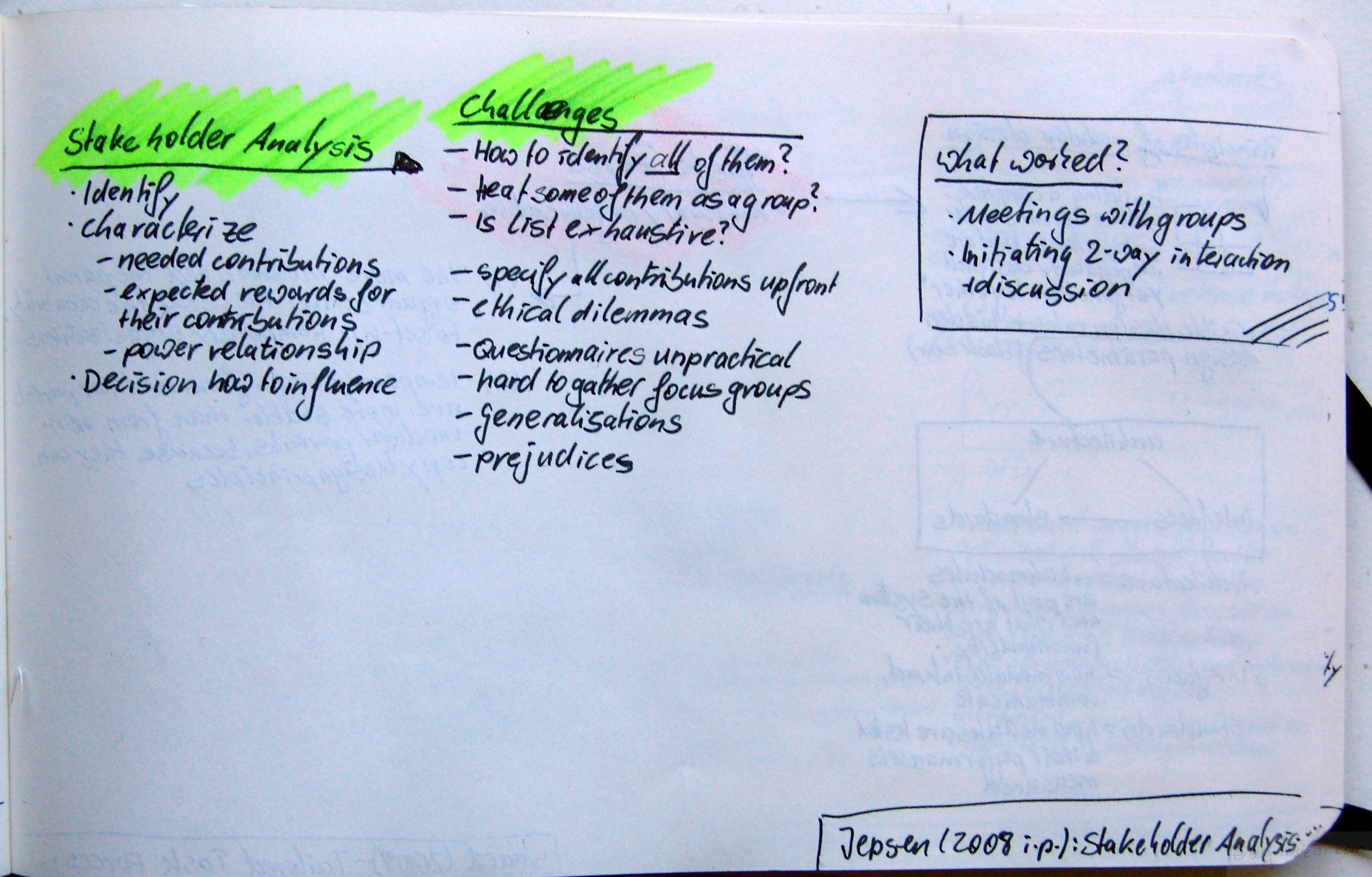

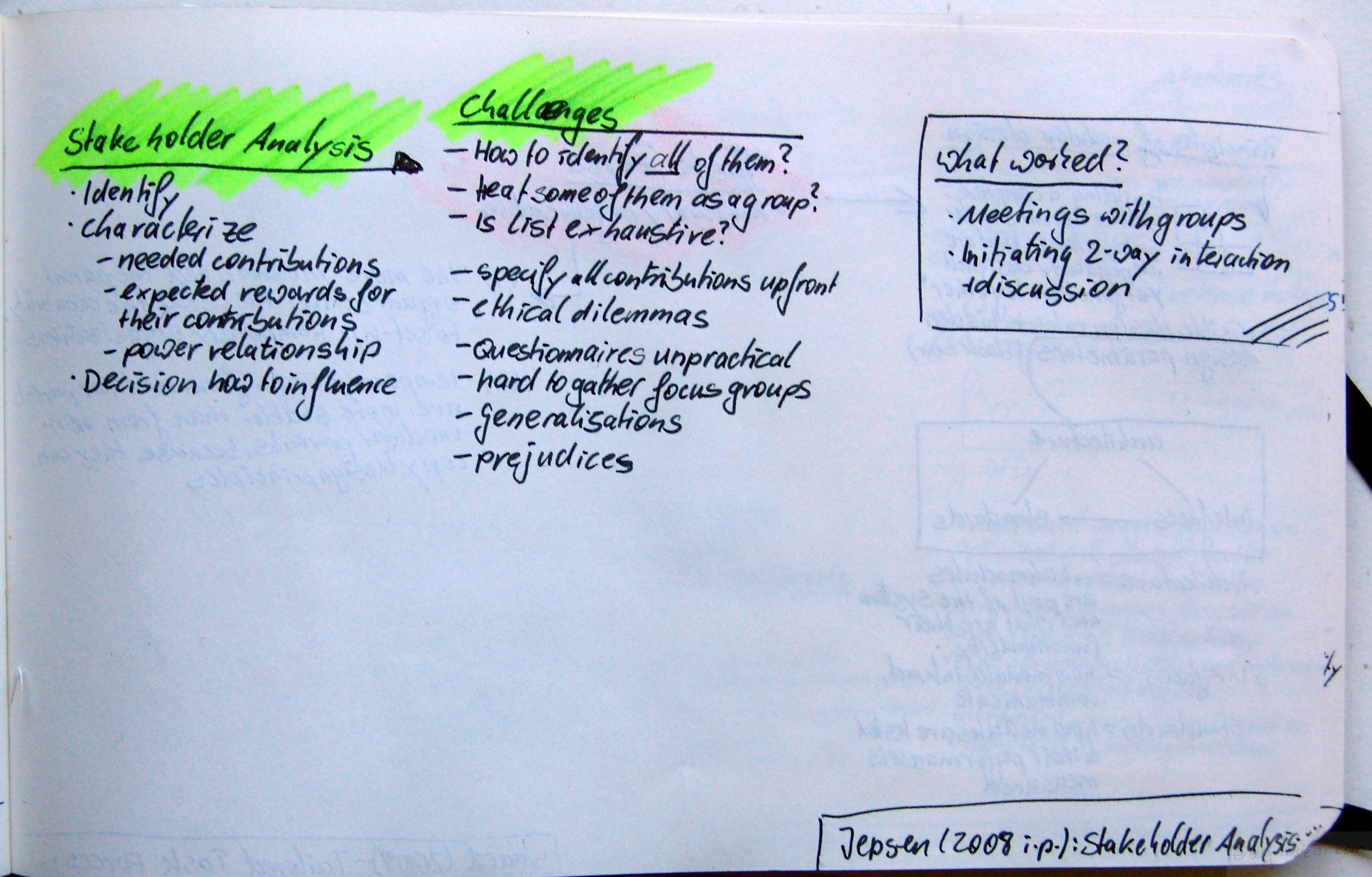

Jepsen, Ann Lund; Eskerod, Pernille: Stakeholder analysis in projects – Challenges in using current guidelines in the real world; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.04.002Update the article has been published in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 27 (2009), No. 4, pp. 335-343.In this small group experiment the authors presented four project managers with the task to analyse their stakeholders. The participants needed to identify, characterise, and decide how to influence stakeholders. To characterise them the project managers defined which contributions they needed from each stakeholder, what they would use a reward for contributing, and which power relationship linked manager and stakeholder.The participating managers (all managing renewal projects) identified a list of challenges they faced during this task

Jepsen, Ann Lund; Eskerod, Pernille: Stakeholder analysis in projects – Challenges in using current guidelines in the real world; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.04.002Update the article has been published in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 27 (2009), No. 4, pp. 335-343.In this small group experiment the authors presented four project managers with the task to analyse their stakeholders. The participants needed to identify, characterise, and decide how to influence stakeholders. To characterise them the project managers defined which contributions they needed from each stakeholder, what they would use a reward for contributing, and which power relationship linked manager and stakeholder.The participating managers (all managing renewal projects) identified a list of challenges they faced during this task

- Comprehensiveness – How do I ensure that I identified all stakeholders? Is my list exhaustive?

- Simplification – Can I treat some of them as a group?

- Foresight – How can I ensure I specified all needed contributions upfront?

- Biases – Ethical dilemmas, prejudices, generalisations about stakeholders

- Tools – Suggested questionnaires are not practical, it’s hard to gather focus groups

Nevertheless Jepsen & Eskerod found two approaches that worked quite well – (1) Meetings with groups of stakeholders and (2) Initiating two-way interactions and discussions with stakeholders.Involve them early, involve them constantly!

Posted in Stakeholder Management | No Comments »

Oktober 20th, 2008

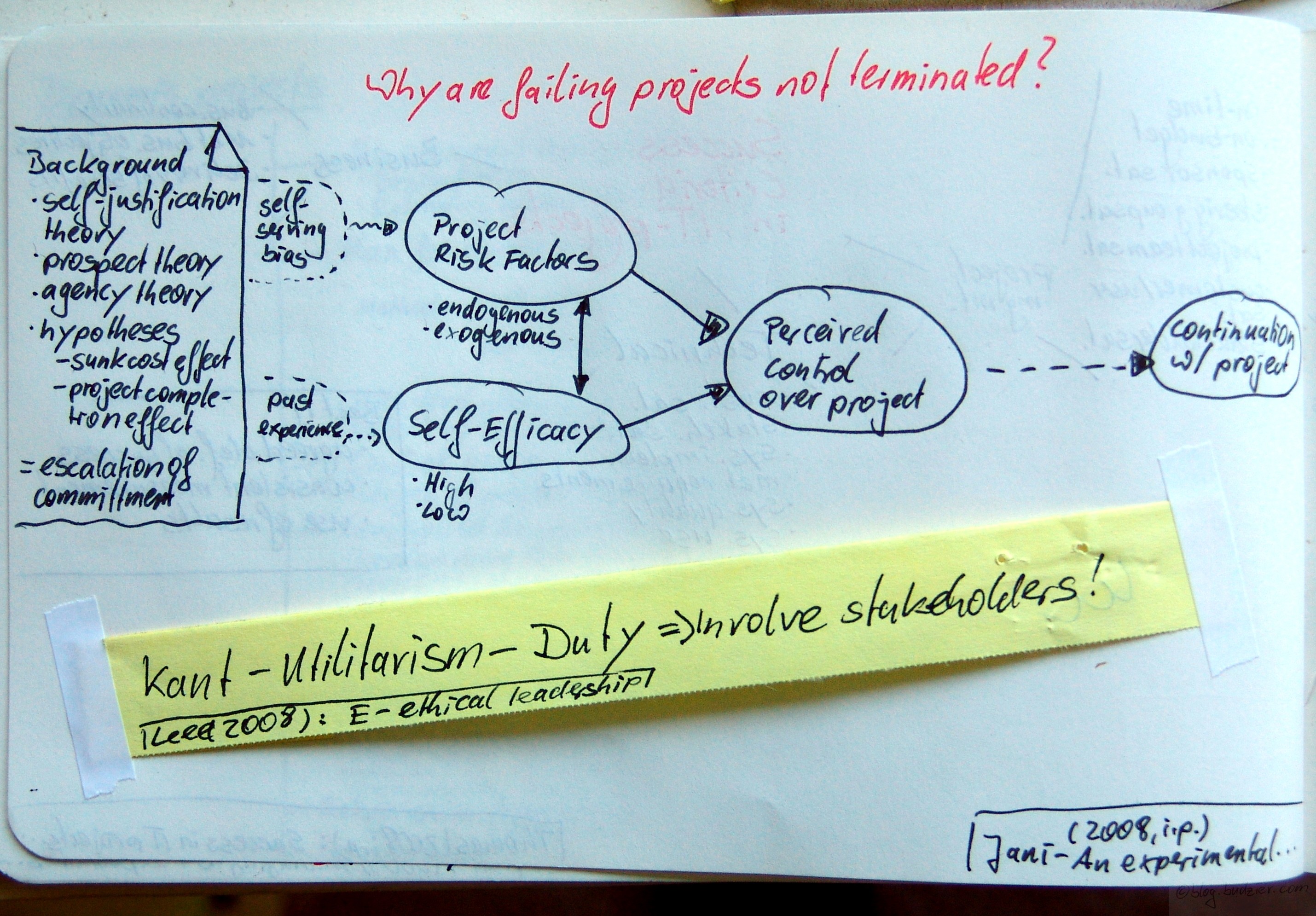

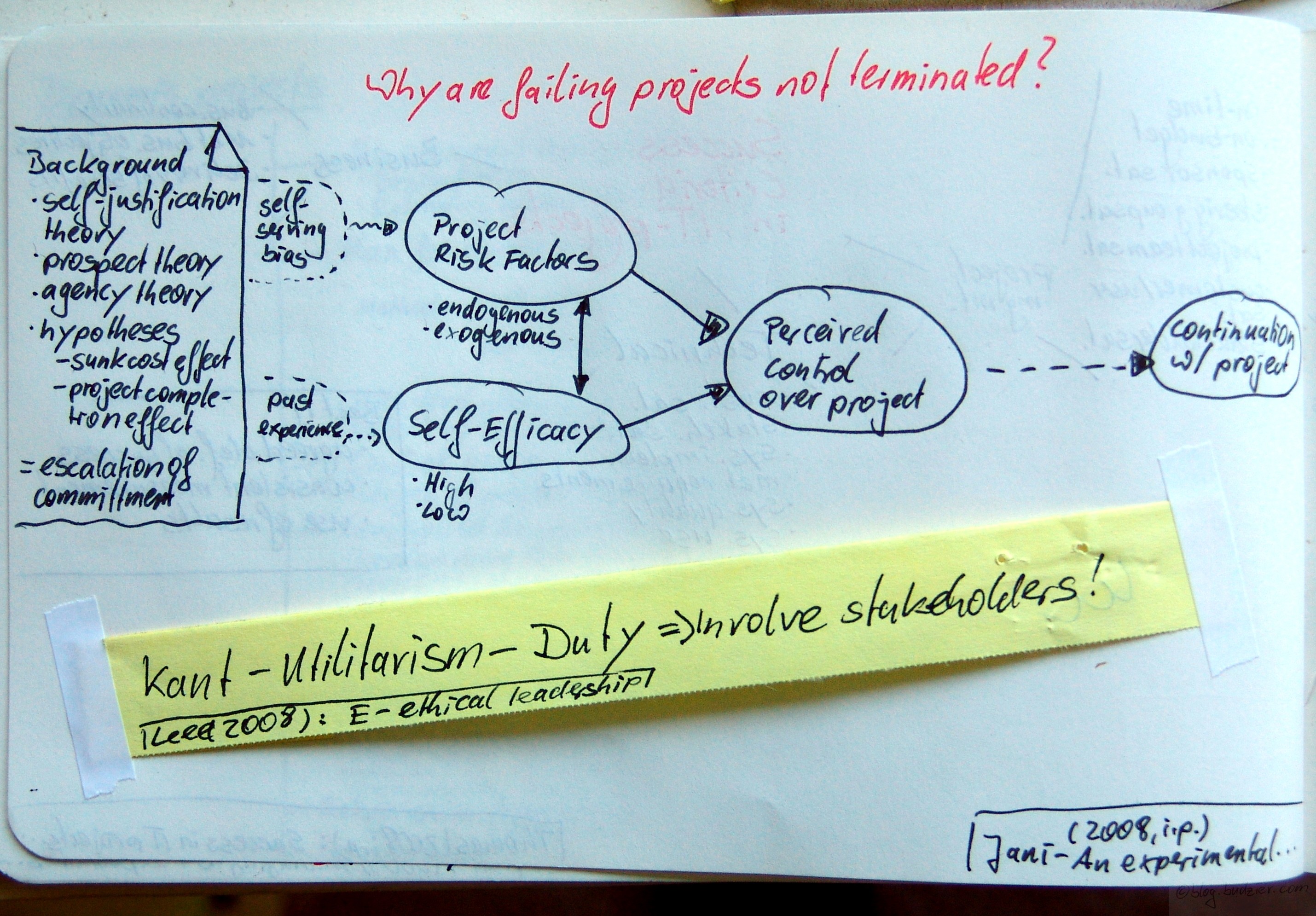

Jani, Arpan: An experimental investigation of factors influencing perceived control over a failing IT project; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 7, pp. 726-732.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.06.004

Jani wants to analyse why failing projects are not terminated, a spiralling development also called escalation of commitment (I posted about a case discussion of the escalation of commitment on the TAURUS project). Jani performed a computer simulated experiment to show the antecedents of a continuation decision.

He rooted the effect of escalating commitment on the self-justification theory, prospect theory, agency theory, and also on sunk cost effects & project completion effects.

Self-justification motivates behaviour to justify attitudes, actions, beliefs, and emotions. It is an effect of cognitive dissonance and an effective cognitive strategy to reduce the dissonance. An example for this behaviour is continuing with a bad behaviour, because stopping it would question the previous decision (= escalation of commitment).

Another example is bribery. People bribed with a large amount of money, tend not to change their attitudes, which were unfavourable otherwise there was nor reason to bribe them in the first place. But Festinger & Carlsmith reported that bribery with a very small amount of money, made people why they accepted the bribe although it had been that small, thus thinking that there must be something to it and changing their attitude altogether. Since I did it, and only got 1 Dollar is a very strong dissonance. Here is a nice summary about their classic experiments. Here is one of their original articles.

Jani argues that all these theoretical effects fall into two factors – (1) self-serving bias and (2) past experience. These influence the judgement on his two antecedents – (1) project risk factors (endogeneous and exogeneous) and (2) task specific self-efficacy. The latter is measured as a factor step high vs. low and describes how you perceive your capability to influence events that impact you (here is a great discussion of this topic by Bandura).

The two factors of project risk and task specific self-efficacy then influence the perceived control over the project which influences the continuation decision. Jani is able to show that task specific self-efficacy moderates the perceived project control. In fact he manipulated the project risks to simulate a failing projects, at no time participants had control over the outcome of their decisions. Still participants with a higher self-efficacy judged their perceived control significantly higher than participants with lower self-efficacy. This effect exists for engogenous and exogenous risk factors alike.

The bottom-line of this experiment is quite puzzling. A good project manager, who has a vast track record of completing past projects successfully, tends to underestimate the risks impacting the project. Jani recommends that even with great past experiences on delivering projects, third parties should always review project risks. Jani asks for caution using this advice since his experiment did not prove that joint evaluation corrects for this bias effectively.

Lee, Margaret E.: E-ethical leadership for virtual project teams; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press (2008).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.05.012

I quickly want to touch on this article, since the only interesting idea which stroke me was that Lee did draw a line from Kant to Utilitarism to the notion of Duty. She then concludes that it is our Kantesian, Utalitarian duty to involve stakeholders.

Posted in Decision Making, Failed Projects, Leadership, Portfolio Management, Program Management, Project Recovery | 1 Comment »

Oktober 9th, 2008

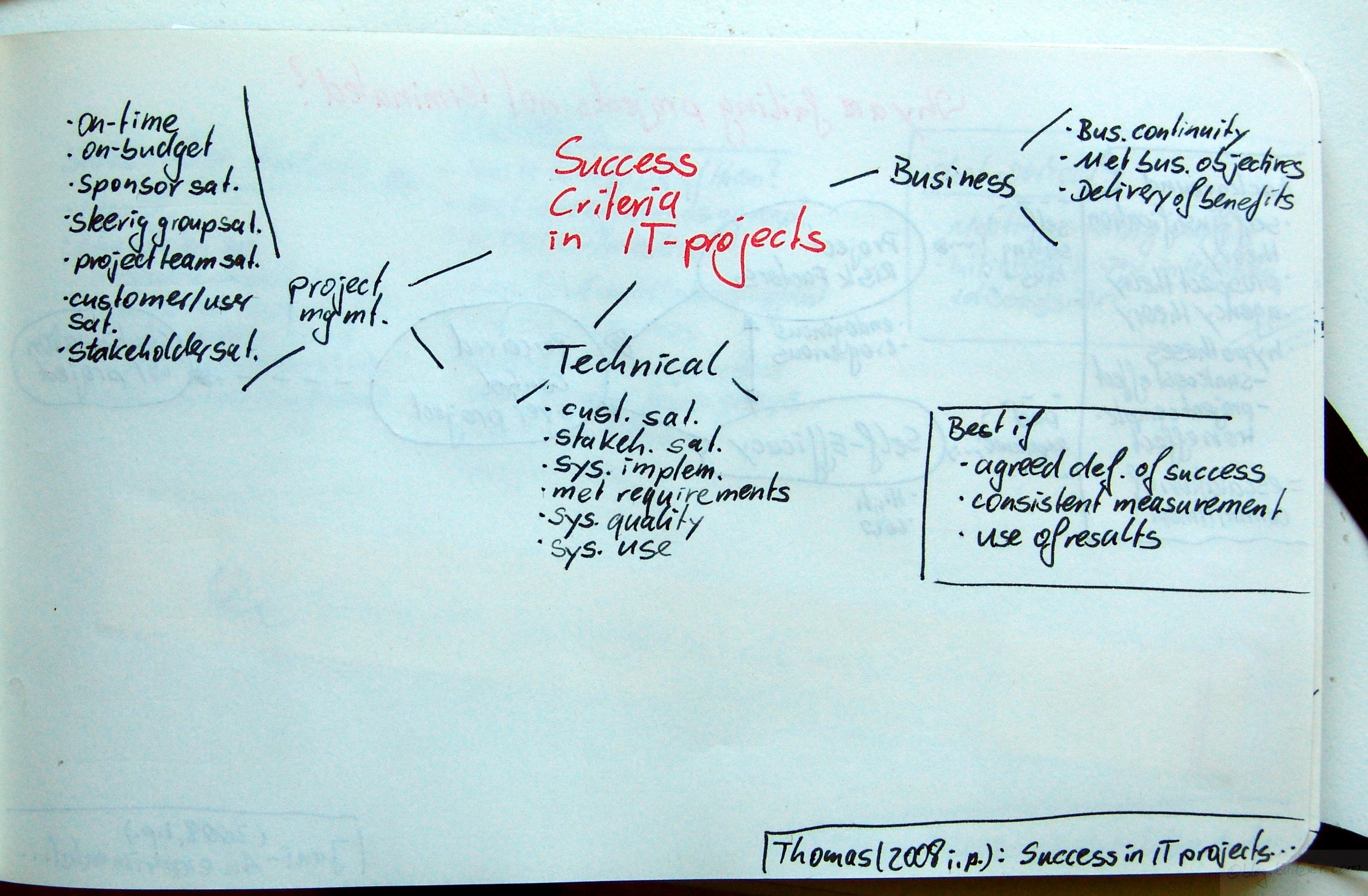

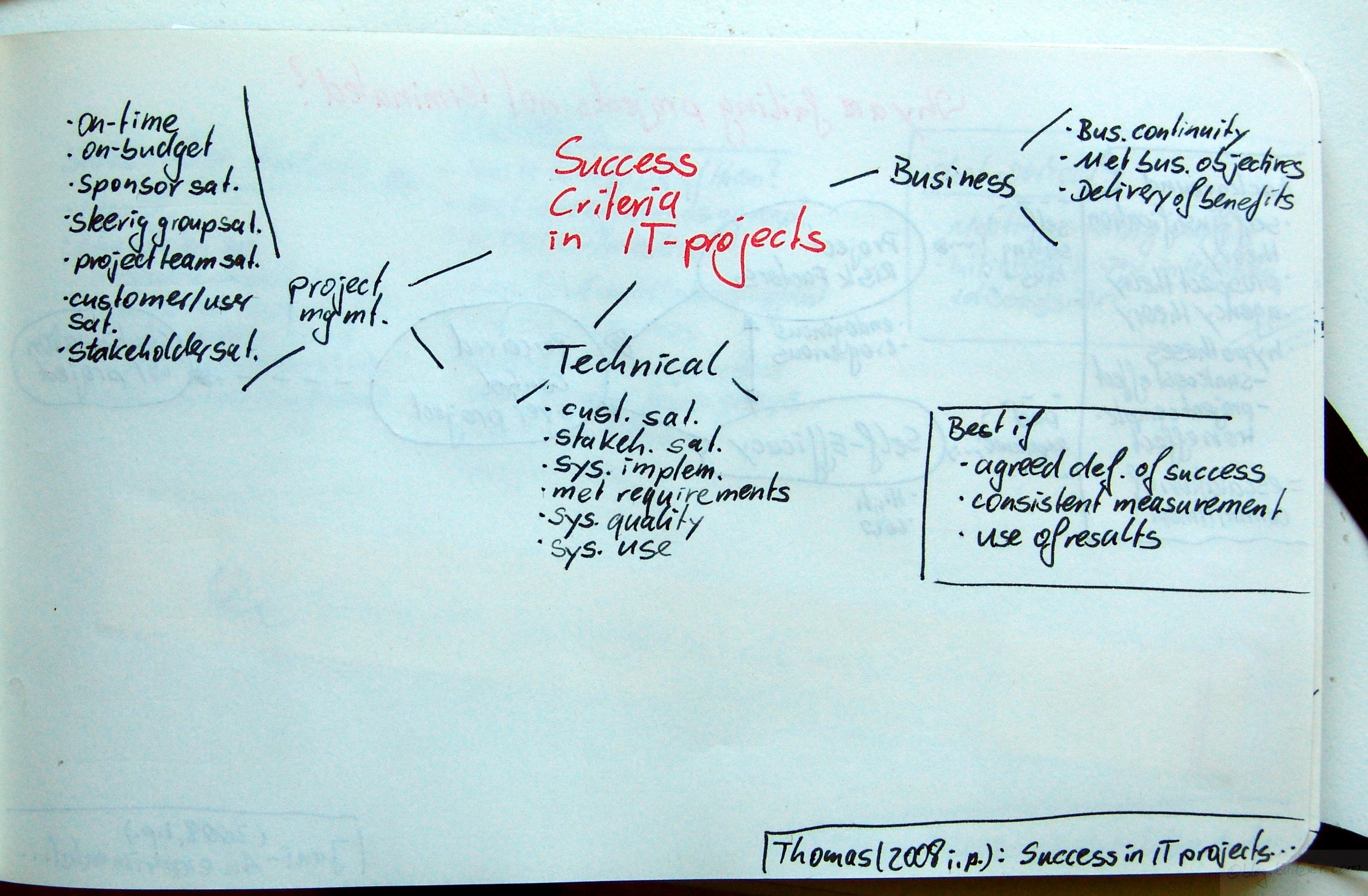

Thomas, Graeme; Fernández, Walter: Success in IT projects – A matter of definition?; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press (2008).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.06.003

A lot of IT projects are not successful. One of the problems seems to be that success is a tricky concept. The GAO considers (IT) projects as challenged if they are about to exceed their budget and/or schedule by 10%. As such most projects fail.

Several best practice studies have pointed out that agreeing on success criteria is better down upfront, they should be consistently measured, which includes a proper baseline, and their measurement results must be used.

Thomas & Fernández collect examples for IT project success criteria in three broad categories: project management, technical, and business criteria.

Project Management Criteria

- On-time

- On-budget

- Sponsor satisfaction

- Steering group satisfaction

- Project team satisfaction

- Customer/user satisfaction

- Stakeholder satisfaction

Technical Criteria

- Customer satisfaction

- Stakeholder satisfaction

- System implementation

- Meeting requirements

- System quality

- System use

Business Criteria

- Business continuity

- Meeting business objectives

- Delivery of benefits

Posted in Failed Projects, IT Project, Success Criteria | 1 Comment »

Oktober 9th, 2008

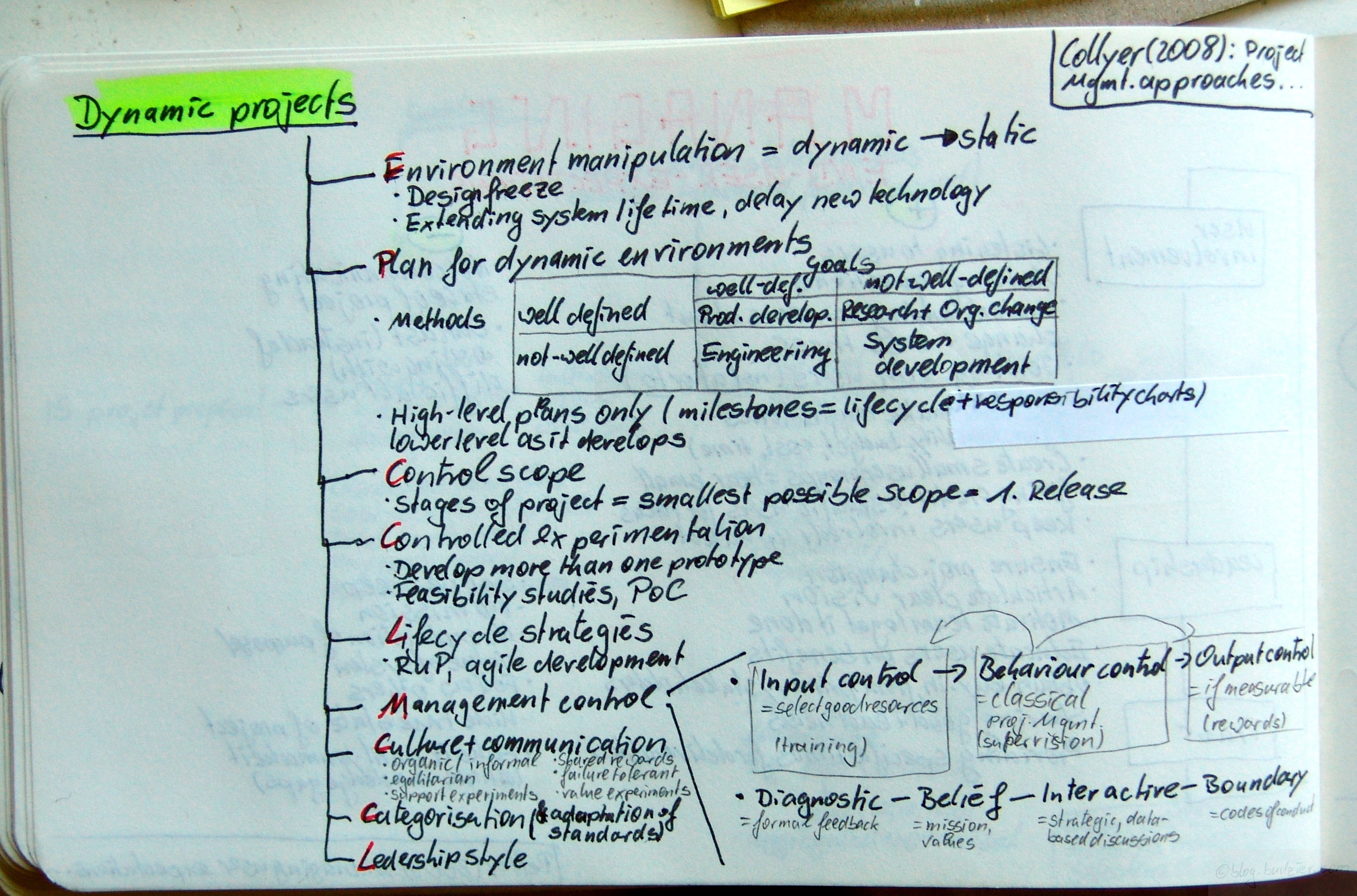

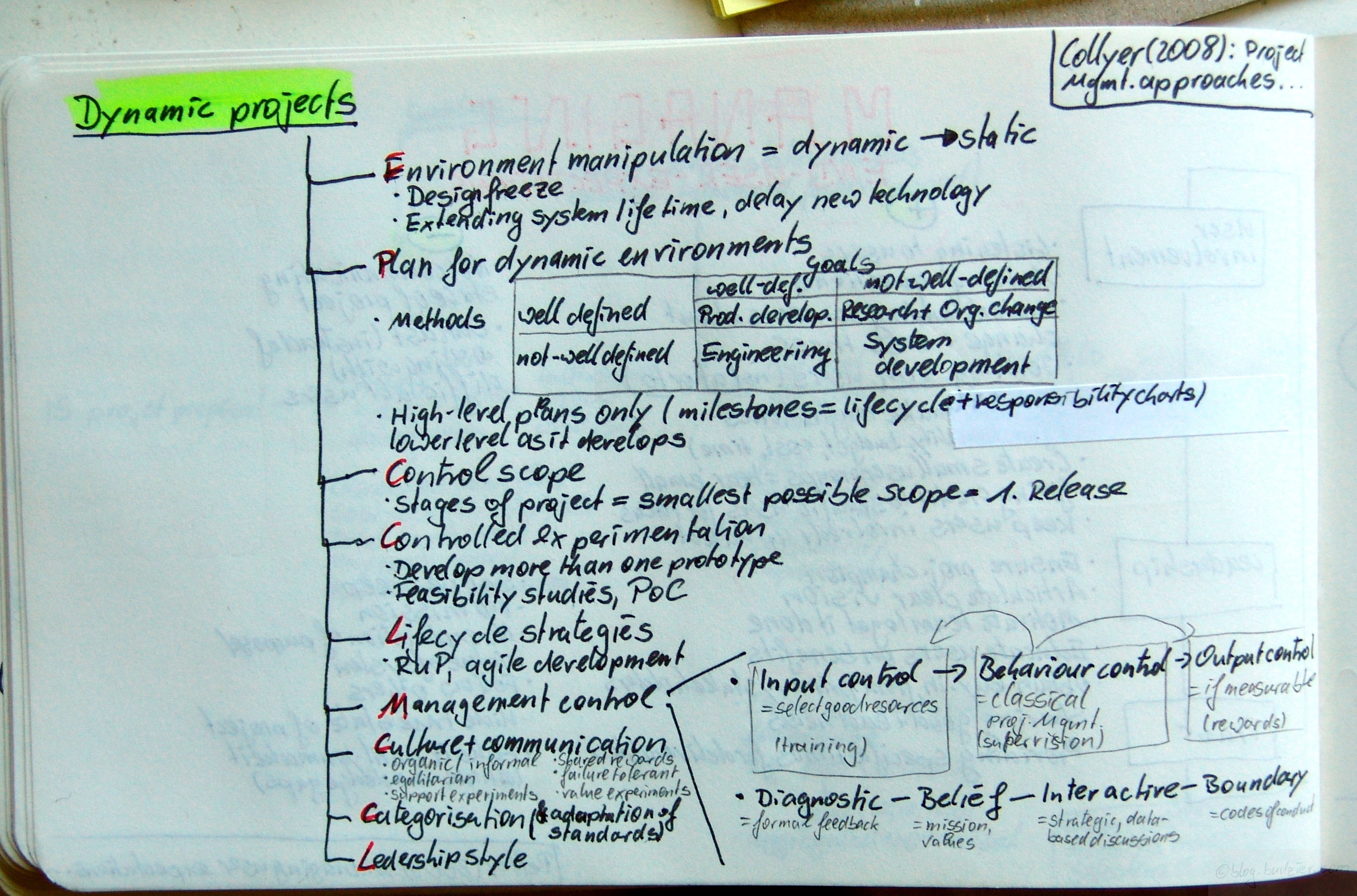

Collyer, Simon: Project management approaches for dynamic environments; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press (2008).http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.04.004Update this article has been published in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 27 (2009), No. 4, pp. 355-364. There it is again: Complexity, this time under the name of Dynamic Project Environments. I admit that link is a bit of a stretch. Complexity has been described as situations, where inputs generate surprising outputs. Collyer on the other hand focuses special project management strategies to succeed in changing environments. The author’s example is the IT project, which inherently bears a very special dynamic.He discusses eight different approaches to cope with dynamics. (1) Environment manipulation, which is the attempt to transform a dynamic environment into a static environment. Examples commonly employed are design freezes, extending a systems life time, and leapfrogging or delaying new technology deployment.(2) Planning for dynamic environments. Collyer draws a framework where he classifies projects on two dimensions. Firstly, if their methods are well defined or not, and secondly if the goals are well defined or not. For example he classifies the System Development project as ill-defined and ill-defined. This is a point you could argue about, because some people claim that IT projects usually have well-defined methodologies, but lack clear goals. Collyer suggest scaling down planning. Plan milestones according to project lifecycle stages, and detail when you get there. He recommends spending more time on RACI-matrices than on detailed plans.(3) Control scope, which is quite the obivious thing to try to achieve – Collyer recommends to always cut the project stages along the scope and make the smallest possible scope the first release.(4) Controlled experimentation. The author suggest that experimentation supports sense-making in a dynamic environment. Typical examples for experimentation are prototyping (Collyer recommends to always develop more than one prototype), feasibility studies, and proofs of concept.(5) Lifecycle strategies, although bearing similarities to the scope control approaches he proposes this strategy deals with applying RuP and agile development methods, to accelerate the adaptability of the project in changing environments.(6) Managment control, as discussed earlier in this post every project uses a mix of different control techniques. Collyer suggest deviating from the classical project management approach of controlling behaviour by supervision, in favour for using more input control, for example training to ensure only the best resources are selected. Besides input control Collyer recommend on focussing on output control as well, making output measurable and rewarding performance.Collyer also discusses a second control framework, which distinguishes control by the abstract management principle. Such as diagnostic control (=formal feedback), control of beliefs (=mission, values), control of interactions (=having strategic, data-based discussions), and boundary control (=defining codes of conduct).Lastly the author discusses two more approaches to succeeding with dynamic environments which are (7) Categorisation and adaptation of standards and (8) Leadership style.

Collyer, Simon: Project management approaches for dynamic environments; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press (2008).http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.04.004Update this article has been published in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 27 (2009), No. 4, pp. 355-364. There it is again: Complexity, this time under the name of Dynamic Project Environments. I admit that link is a bit of a stretch. Complexity has been described as situations, where inputs generate surprising outputs. Collyer on the other hand focuses special project management strategies to succeed in changing environments. The author’s example is the IT project, which inherently bears a very special dynamic.He discusses eight different approaches to cope with dynamics. (1) Environment manipulation, which is the attempt to transform a dynamic environment into a static environment. Examples commonly employed are design freezes, extending a systems life time, and leapfrogging or delaying new technology deployment.(2) Planning for dynamic environments. Collyer draws a framework where he classifies projects on two dimensions. Firstly, if their methods are well defined or not, and secondly if the goals are well defined or not. For example he classifies the System Development project as ill-defined and ill-defined. This is a point you could argue about, because some people claim that IT projects usually have well-defined methodologies, but lack clear goals. Collyer suggest scaling down planning. Plan milestones according to project lifecycle stages, and detail when you get there. He recommends spending more time on RACI-matrices than on detailed plans.(3) Control scope, which is quite the obivious thing to try to achieve – Collyer recommends to always cut the project stages along the scope and make the smallest possible scope the first release.(4) Controlled experimentation. The author suggest that experimentation supports sense-making in a dynamic environment. Typical examples for experimentation are prototyping (Collyer recommends to always develop more than one prototype), feasibility studies, and proofs of concept.(5) Lifecycle strategies, although bearing similarities to the scope control approaches he proposes this strategy deals with applying RuP and agile development methods, to accelerate the adaptability of the project in changing environments.(6) Managment control, as discussed earlier in this post every project uses a mix of different control techniques. Collyer suggest deviating from the classical project management approach of controlling behaviour by supervision, in favour for using more input control, for example training to ensure only the best resources are selected. Besides input control Collyer recommend on focussing on output control as well, making output measurable and rewarding performance.Collyer also discusses a second control framework, which distinguishes control by the abstract management principle. Such as diagnostic control (=formal feedback), control of beliefs (=mission, values), control of interactions (=having strategic, data-based discussions), and boundary control (=defining codes of conduct).Lastly the author discusses two more approaches to succeeding with dynamic environments which are (7) Categorisation and adaptation of standards and (8) Leadership style.

Posted in Complexity, Culture, Decision Making, Hard and soft projects, IT Project, Methodology, Project Organisation, Project Strategy, Strategy, Uncertainty management | 2 Comments »

Oktober 7th, 2008

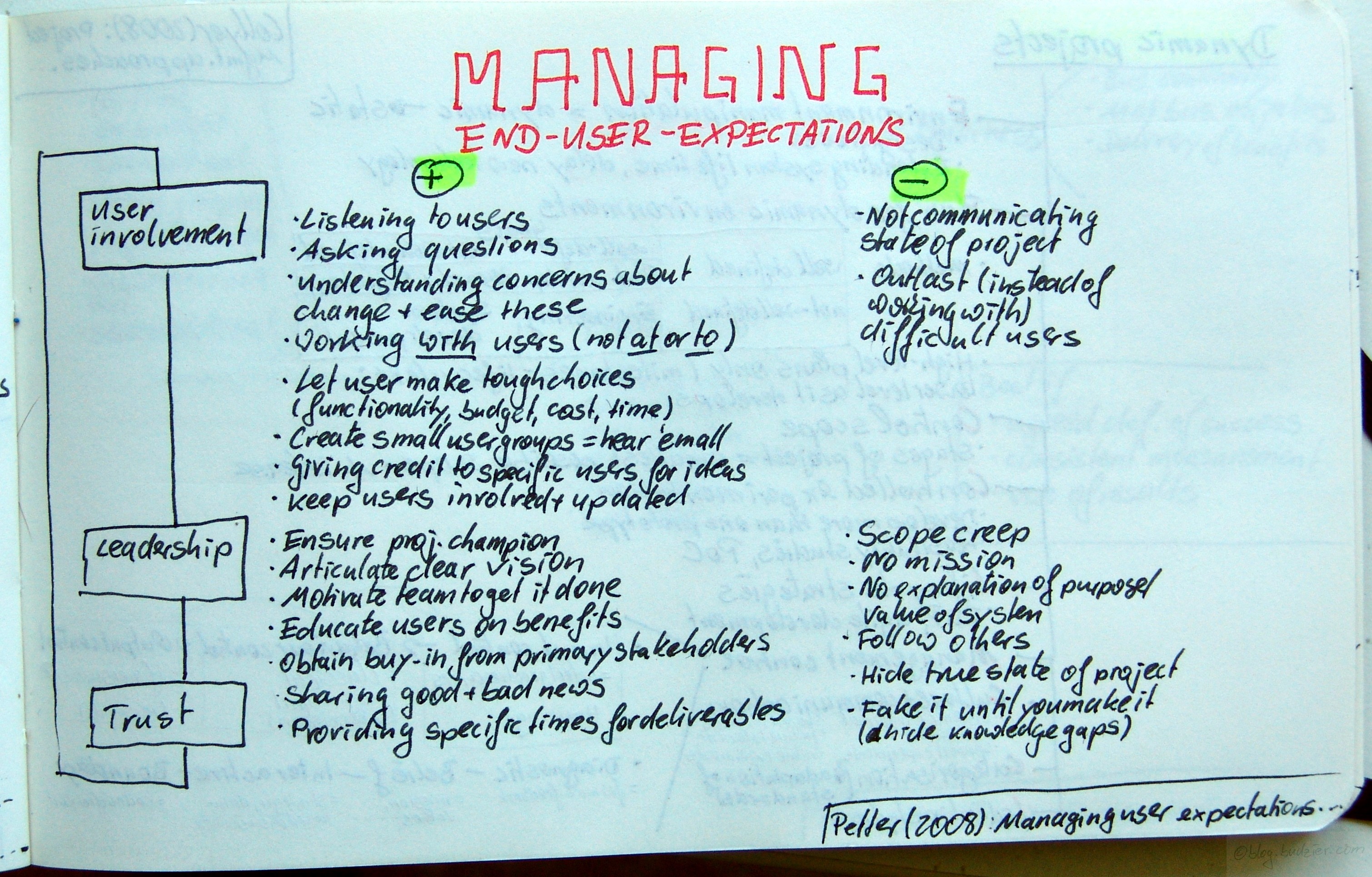

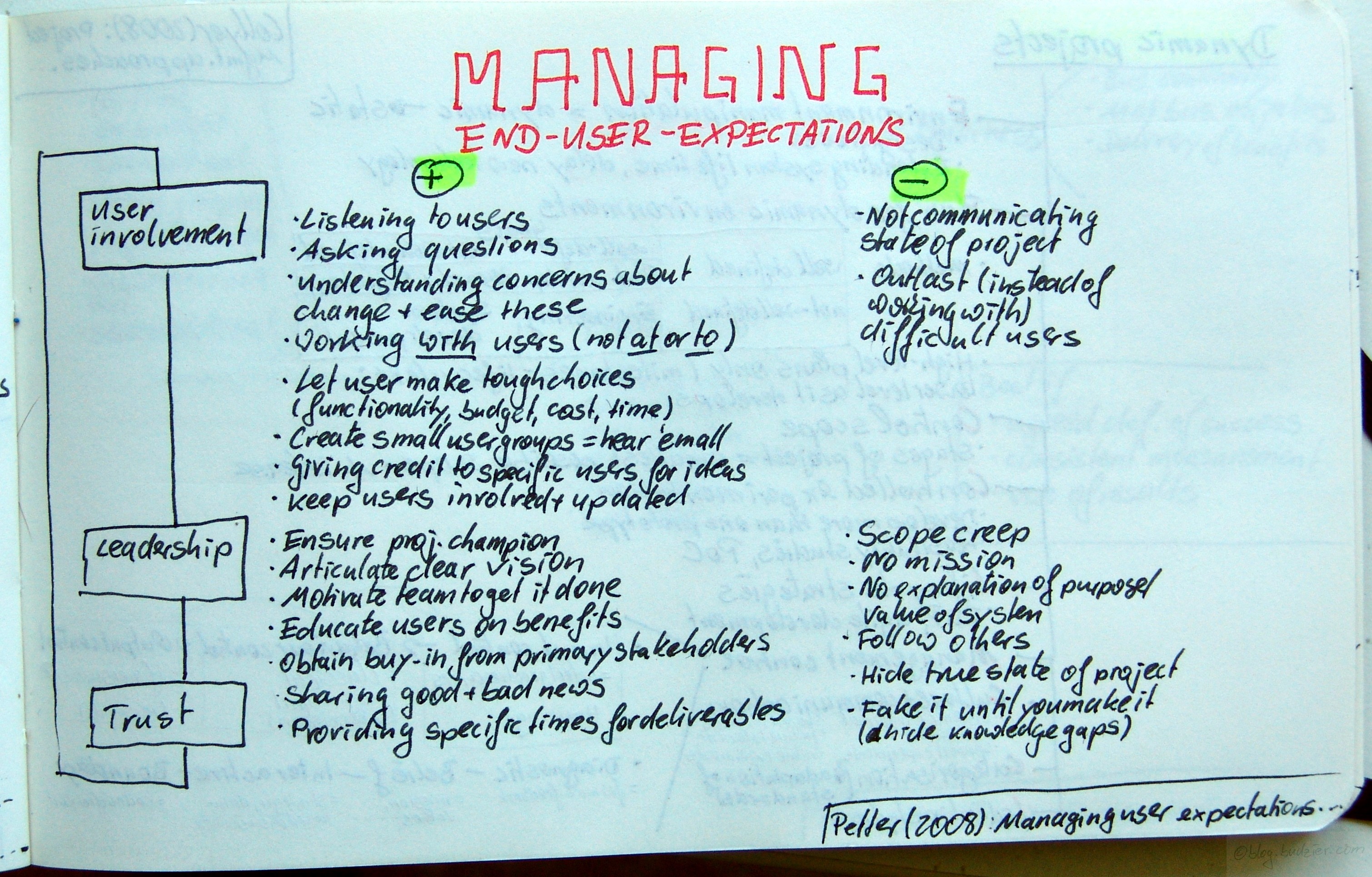

Petter, Stacie: Managing user expectations on software projects – Lessons from the trenches; in: International Journal of Project Mangement, in press (2008).

doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.05.014

Petter interviewed 12 project management professionals on managing the end-user expectations. What worked and what did not work?

The conclusions cover three broad areas – end user involvement, leadership, and trust. As far as user involvement is concerned the practices that work included

- Listening to users

- Asking questions

- Understanding concerns about change and actively ease these

- Working with the user (not at or to them)

- Let user make tough choices, e.g., on functionality, budget, cost, time

- Create small user groups to hear them all

- Giving credit to specific users for ideas

- Keep users involved and updated throughout the project

What did not work were – not communicating the project status, and trying to outlast difficult users.

On the leadership dimension useful practices mentioned include

- Ensure project champion

- Articulate clear vision

- Motivate team to get it done

- Educate users on benefits

- Obtain buy-in from primary stakeholders

Factors leading to end-user dissatisfaction were

- Scope creep

- No mission

- No explanation of purpose/value of the system

- Follow others

Trust building activities that worked well, were sharing good and bad news, and providing specific times for deliverables. What did not work were hiding the true status of the project, and ‚fake it until you make it‘ also known as hiding knowledge gaps.

Posted in Case Study, Critical Incident Technique, Critical Success Factors, Failed Projects, IT Project, Leadership, Stakeholder Management, Trust | 4 Comments »

Oktober 7th, 2008

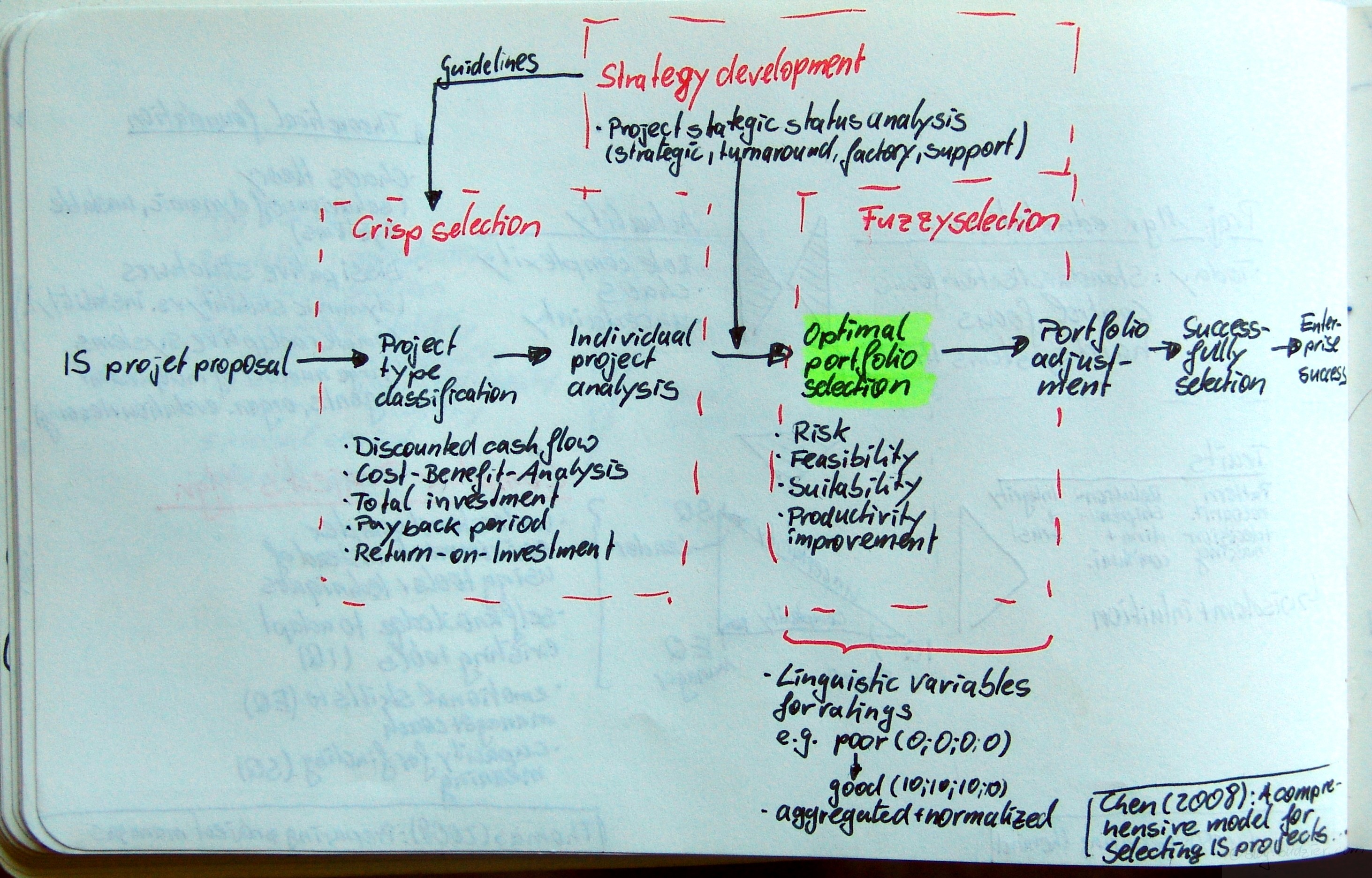

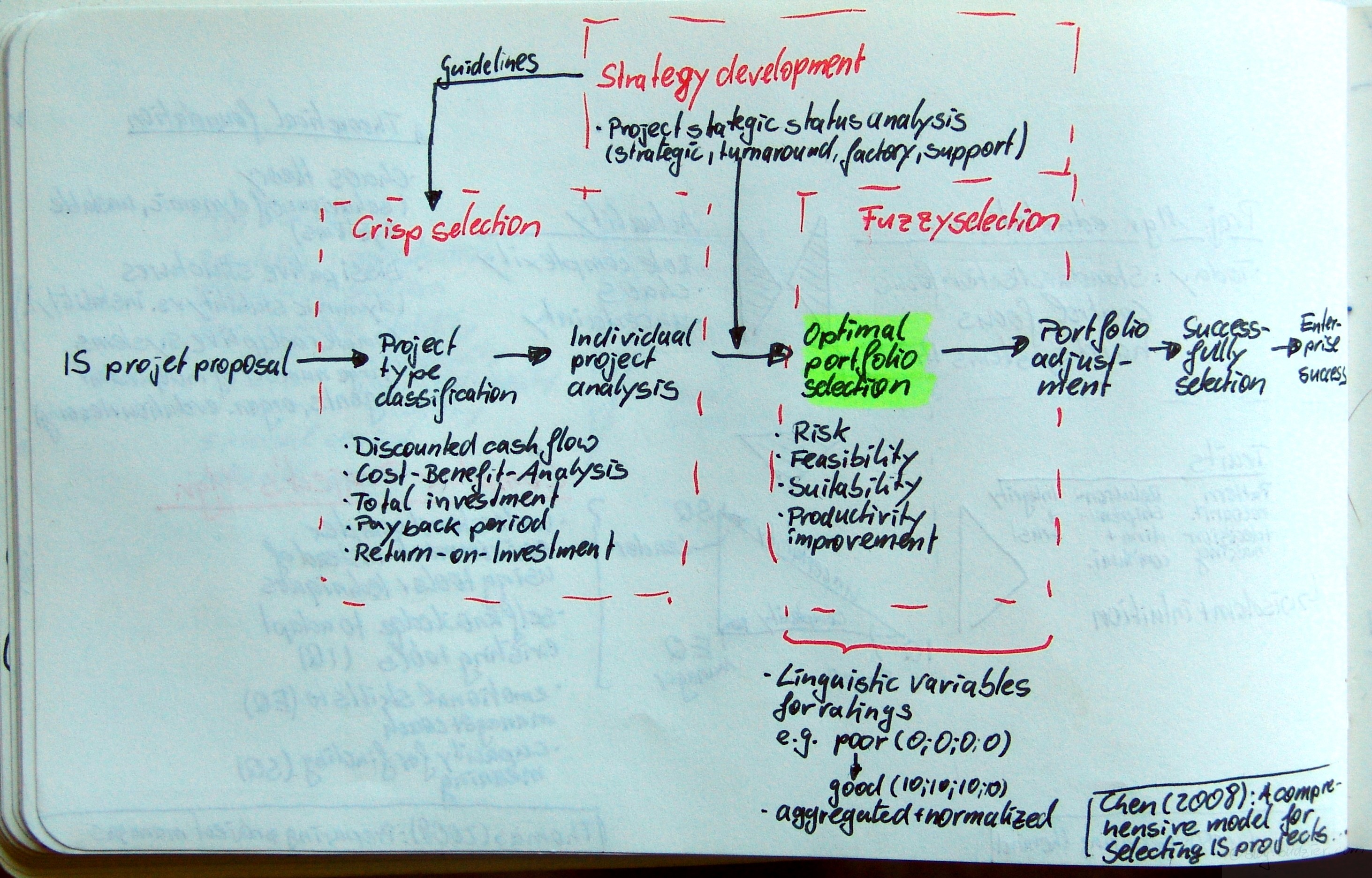

Chen, Chen-Tung; Cheng, Hui-Ling: A comprehensive model for selecting information system project under fuzzy environment; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press.doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.04.001Update: this article has been published in: International Journal of Project Management Vol. 27 (2009), No. 4, pp. 389399.Upfront management is an ever growing body of research and currently develops into it’s own profession. In this article Chen & Cheng propose a model for the optimal IT project portfolio selection. They outline a seven step process from the IT/IS/ITC project proposal to the enterprise success

Chen, Chen-Tung; Cheng, Hui-Ling: A comprehensive model for selecting information system project under fuzzy environment; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press.doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.04.001Update: this article has been published in: International Journal of Project Management Vol. 27 (2009), No. 4, pp. 389399.Upfront management is an ever growing body of research and currently develops into it’s own profession. In this article Chen & Cheng propose a model for the optimal IT project portfolio selection. They outline a seven step process from the IT/IS/ITC project proposal to the enterprise success

- IS/IT/ITC project proposal

- Project type classification

- Individual project analysis

- Optimal portfolio selection

- Portfolio adjustment

- Successfully selection

- Enterprise success

Behind the process are three different types of selection methods and tools – (1) crisp selection, (2) strategy development, and (3) fuzzy selection.The crisp selection is the first step in the project evaluation activities. It consists of different factual financial analyses, e.g. analysis of discounted cash flow, cost-benefits, total investment, payback period, and the return on investment.Strategy development is the step after the crisp selection, whilst it also impacts the first selection step by setting guidelines on how to evaluate the project crisply. Strategy development consists of a project strategic status analysis. According to Chen & Cheng’s framework a project falls in one of four categories – strategic, turnaround, factory, or support.The last step is the fuzzy selection. In this step typical qualitative characteristics of a project are evaluated, e.g., risk, feasibility, suitability, and productivity improvements. In this step lies the novelty of Chen & Cheng’s approach. They let the evaluators assign a linguistic variable for rating, e.g., from good to poor. Then each variable is translated into a numerical value, e.g., poor = 0, good = 10. As such, every evaluator produces a vector of ratings for each project, e.g., (0;5;7;2) – vector length depends on the number of characteristics evaluated. These vectors are then aggregated and normalised.[The article also covers an in-depth numerical example for this proposed method.]

Posted in IT Project, Life Cycle Managment, Multi-project management, Planning, Portfolio Management, Program initiation, Project Selection, Risk Management, Tools, Uncertainty management, Value | 4 Comments »

Oktober 7th, 2008

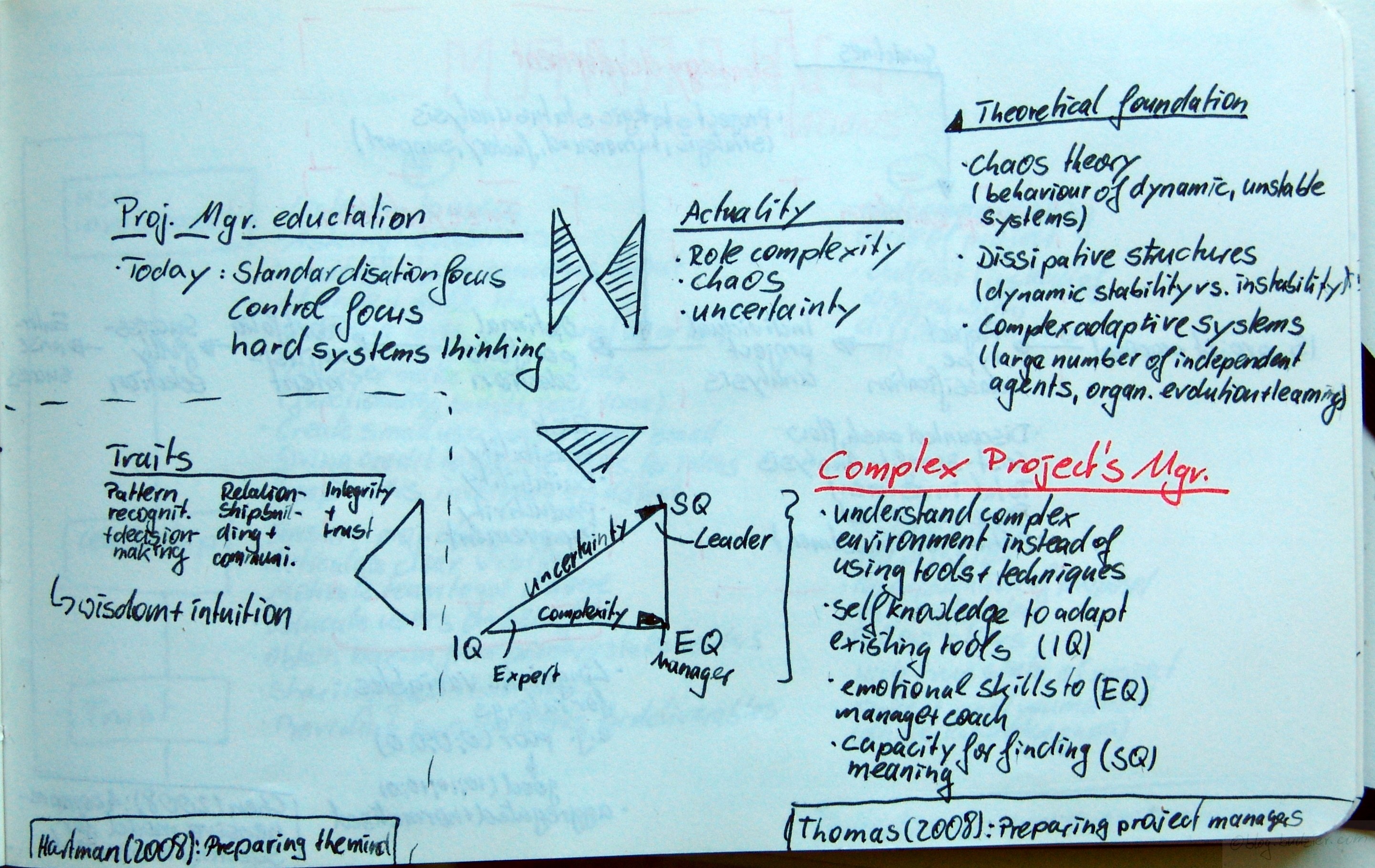

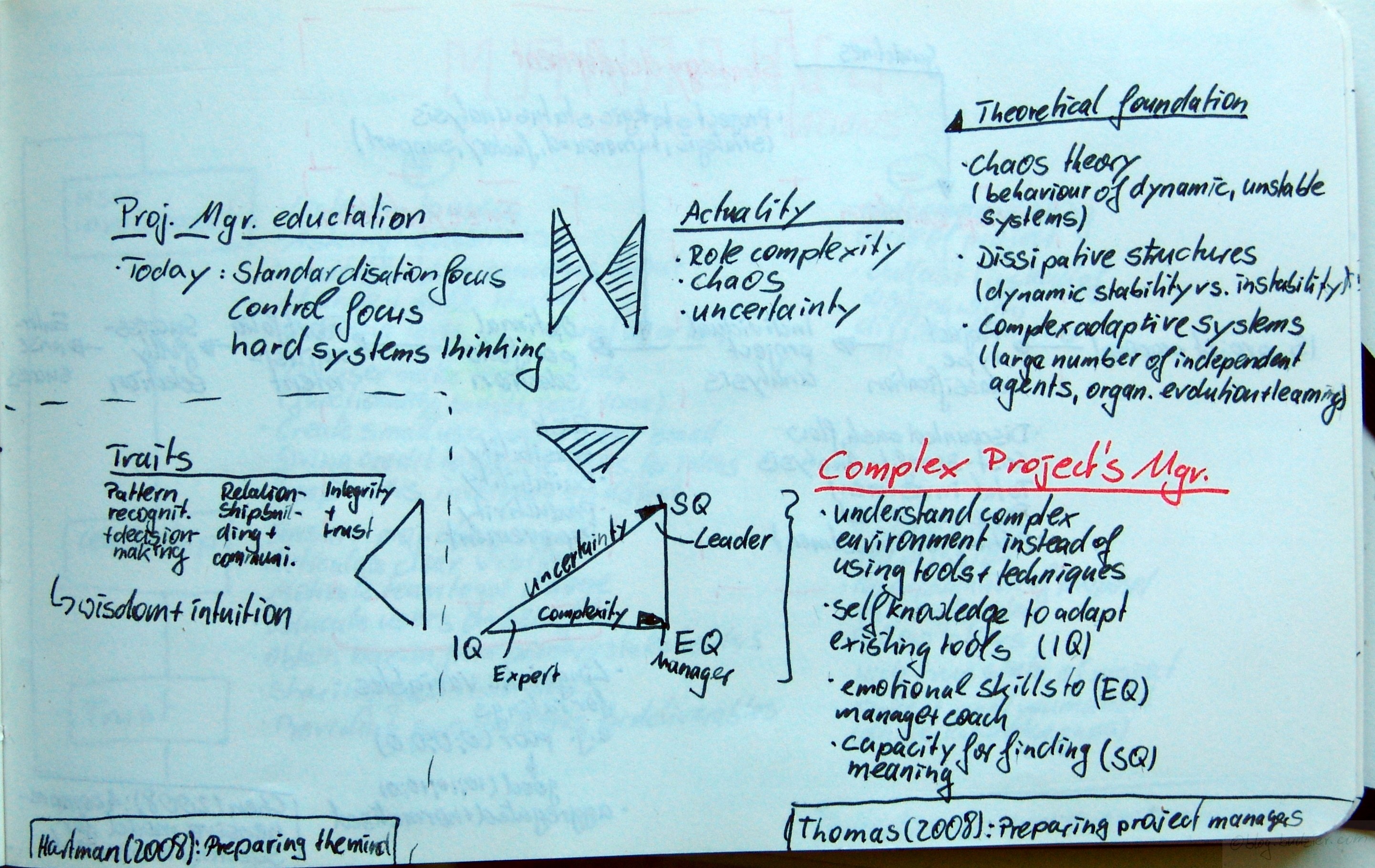

Thomas, Janice; Mengel, Thomas: Preparing project managers to deal with complexity Advanced project management education; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), pp. 304-315.

doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.01.001

Hartman, Francis: ; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), pp. 258-267.

doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.01.007

Complexity is a meme that just doesn’t want to die. I wrote before about articles on the foundamentals of complexity theory and project management, about the use of autonomous cells in project organisations and how they prevent complex project systems from failing, and the complex dynamics of project entities in a programme. Not surprisingly this meme has spread into the coaching and project management education world where there is some money to make of it.

Thomas & Mengel argue that the current project manager education is not suited at all to prepare for complex projects. The focus on standardisation, control, and hard systems thinking stands in direct opposition to the actuality of projects, which show high complexity in roles, high degrees of chaos and uncertainty.

Theoretically Thomas & Mengel base their discussion on three complexity/chaos theory concepts

- Chaos theory – explaining the behaviour of dynamic and unstable systems

- Dissipative structures – explaining moment of dynamic stability and instability

- Complex adaptive systems – explaining behaviour of systems with a large number of independent agents, and organisational evolution and learning

So what does it take to be a Complex Project’s Manager?

Thomas & Mengel propose that understanding the complex environment is far more important than using tools and techniques of project management. Furthermore they outline three key capabilities to manage complexity

- IQ – possessing the self-knowledge to adapt existing tools

- EQ – possessing the emotional skills to coach and manage people

- SQ – possessing the capacity for finding meaning

In their framework Thomas & Mengel see most of today’s project managers as Experts, these are project managers heavy on the IQ side of their IQ-EQ-SQ-Triangle. The authors see two developmental strategies. One is coping with uncertainty by moving towards the sense-making SQ corner of the triangle and becoming a Leader. The other developmental direction is coping with complexity by strengthening the EQ corner and becoming a Manager.

Similar ideas are discussed in the paper by Hartman. Altough he does not call the elephant on the table complex project management but he names it dynamic management. Blink or not Blink – Hartman argues that wisdom and intuition are the two desired qualities in a leader with a mind for dynamic management. Furthermore he identifies three traits absolutely necessary

- Pattern recognition & decision-making

- Relationship building & communication

- Integrity & trust

Posted in Complexity, Leadership, Methodology, Personality, Program Management, Standards | 3 Comments »

Oktober 7th, 2008

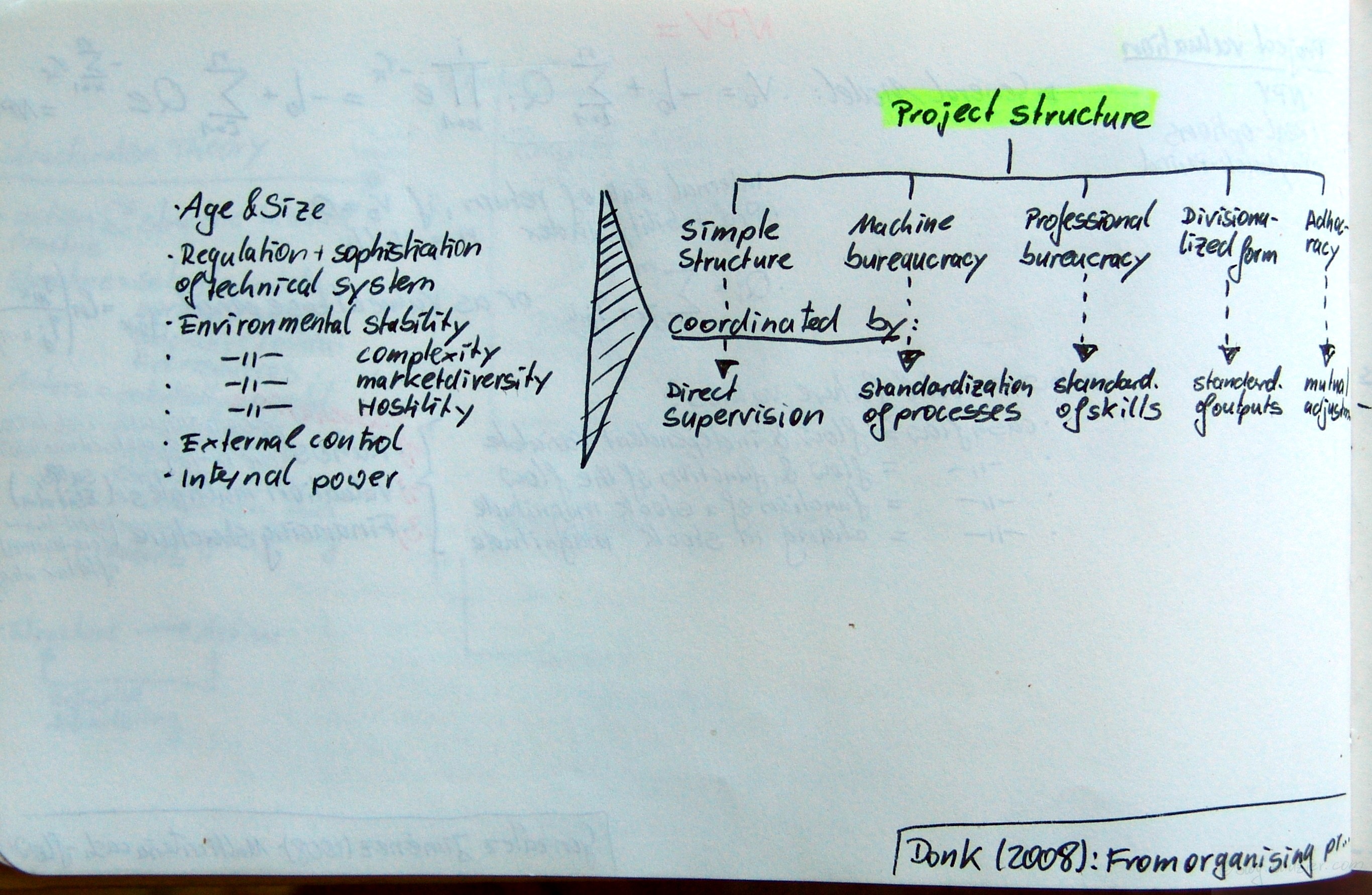

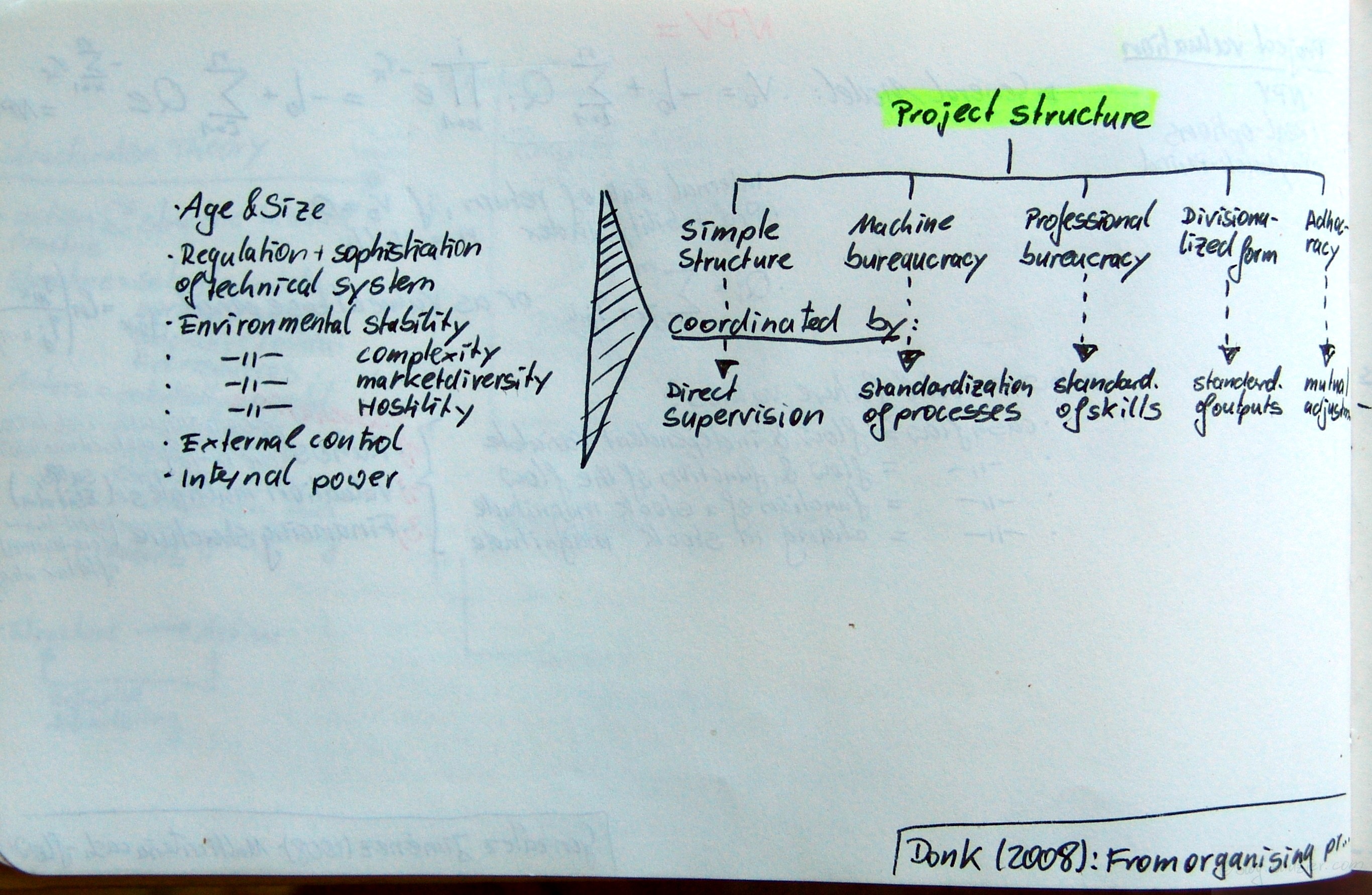

van Donk, Dirk Pieter; Molloy, Eamonn: From organising as projects to projects as organisations; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 2, pp. 129-137.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.05.006

van Donk & Molloy use two case studies to analyse the antecedents of a chosen project structure. Based on the work of Minzberg (1979) the authors identify five different forms of projects which can be mainly distinguished by their coordination mechanism

- Simple structure → direct supervision

- Machine bureaucracy → standardisation of processes

- Professional bureaucracy → standardisation of skills

- Divisionalised form → standardisation of outputs

- Adhocracy → mutual adjustment

The authors identify which antecendents impact the choosen project structure

- Age and size

- Regulation and sophistication of the technical system

- Environmental stability, complexity, market diversity, hostility

- External control

- Internal power

Posted in Actuality Research, Control, Organisation, Temporary organisation | 2 Comments »

Oktober 7th, 2008

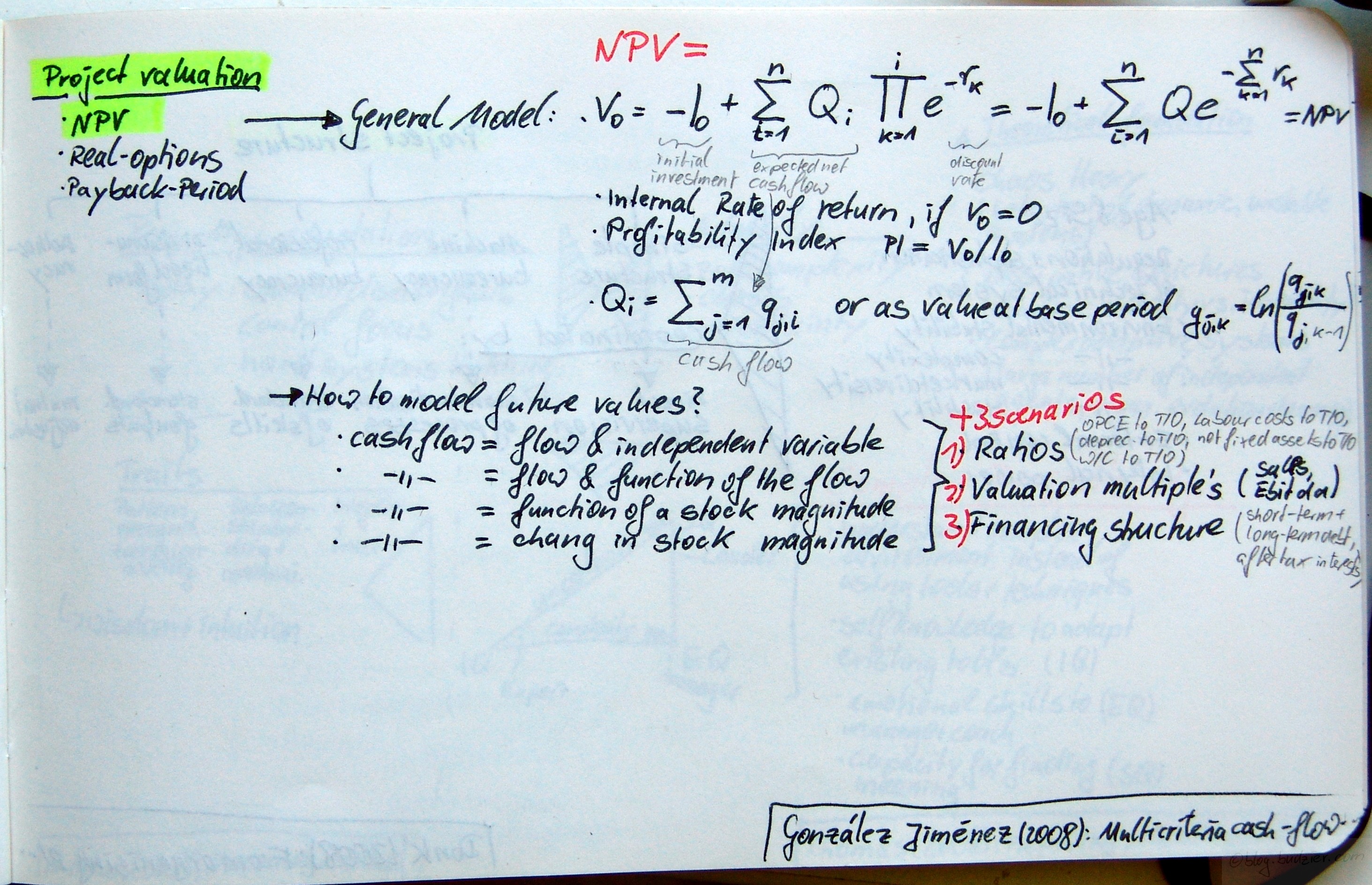

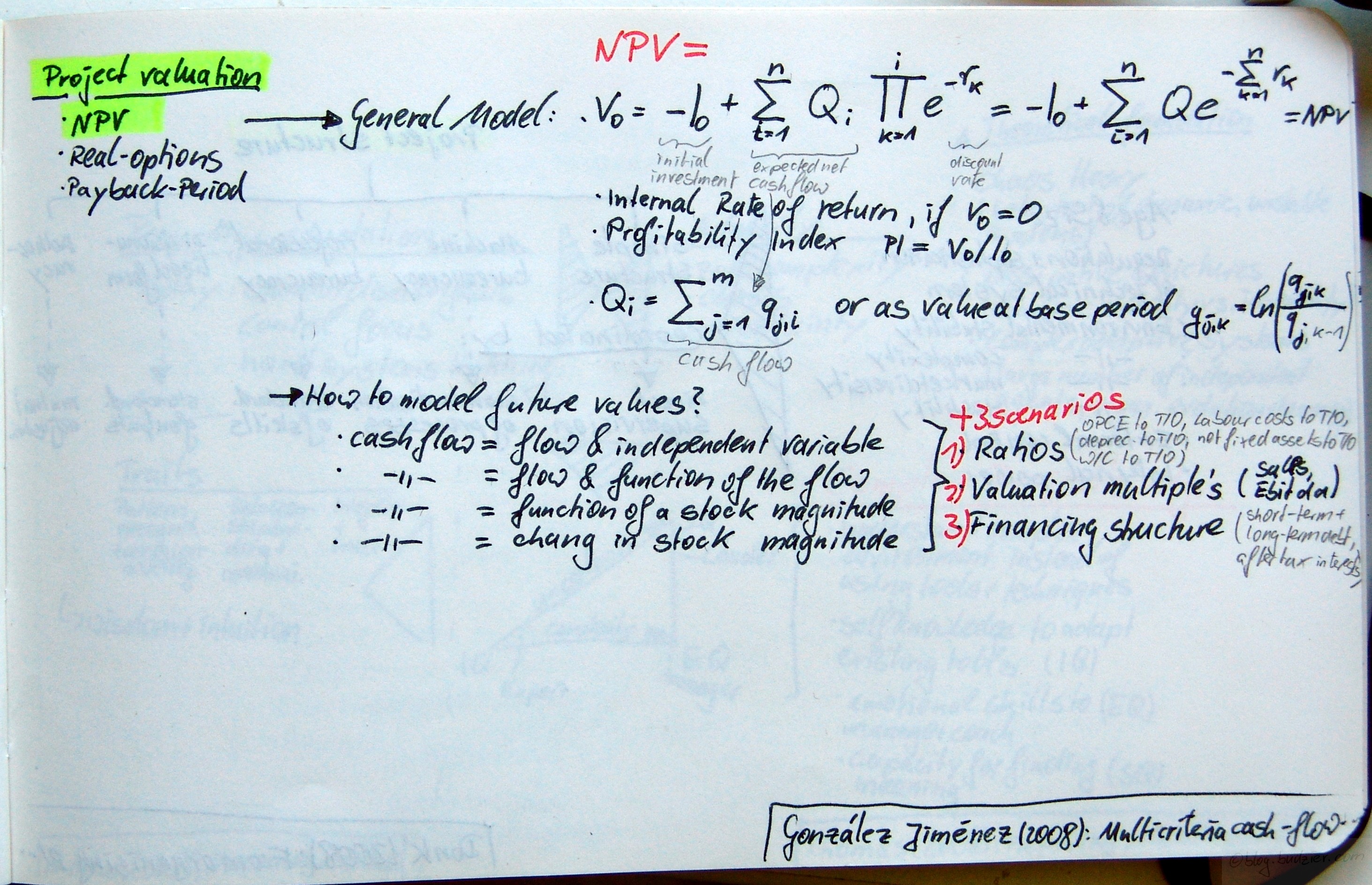

Jiménez, Luis González; Pascual, Luis Blanco: Multicriteria cash-flow modeling and project value-multiples for two-stage project valuation; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 2, pp. 185-194.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.03.012

I am not the expert in financial engineering, though I built my fair share of business cases and models for all sorts of projects and endeavours. I always thought of myself as being not to bad at estimating and modelling impacts and costs, but I never had a deep knowledge of valuation tools and techniques. A colleague was claiming once that every business case has to work on paper with a pocket calculator in your hands. Otherwise it is way to complicated. Anyhow, I do understand the importance of a proper NPV calculation, to say the least even if you do fancy shmancy real options evaluation as in this article here, the NPV is one of the key inputs.

Jiménez & Pascual identify three common approaches to project valuation NPV, real options, and payback period calculations. Their article focusses on NPV calculation. They argue that a NPV calculation consists of multiple cash flow components and each of these has different underlying assumptions, as to it’s risk, value, and return.

The authors start with the general formula for a NPV calculation

NPV = V0 = -I0 + ∑Qi ∏e-rk = -I0 + ∑Q e-∑rk

This formula also gives the internal rate of return (IIR) if V0=0 and the profitability index (PI) is defined as PI = V0/I0. Furthermore Jiménez & Pascual outline two different approaches on how to model the expected net cash flow Qi either as cash flow Qi = ∑qj,i or as value based period gj,k = ln (qj,k/qj,k-1).

The next question is how to model future values of the cash flow without adjusting your assumptions for each and every period. The article’s authors suggest four different methods [the article features a full length explanation and numerical example for each of these]

- Cash Flow = Cash Flow + independent variable

- Cash Flow = Cash Flow + function of the cash flow

- Cash Flow = Function of a stock magnitude

- Cash Flow = Change in stock magnitude

Finally the authors add three different scenarios under which the model is tested and they also show the managerial implications of the outcome of each of these scenarios

- Ratios, such as operating cost and expenses (OPCE) to turnover (T/O), labour costs to T/O, depreciation to TIO, not fixed assets to T/O, W/C to T/O

- Valuation multiples, such as Sales, Ebitda

- Financing structure, such as short term, long term debt, after tax interests

Posted in Decision Making, Methodology, Planning | 3 Comments »

Oktober 3rd, 2008

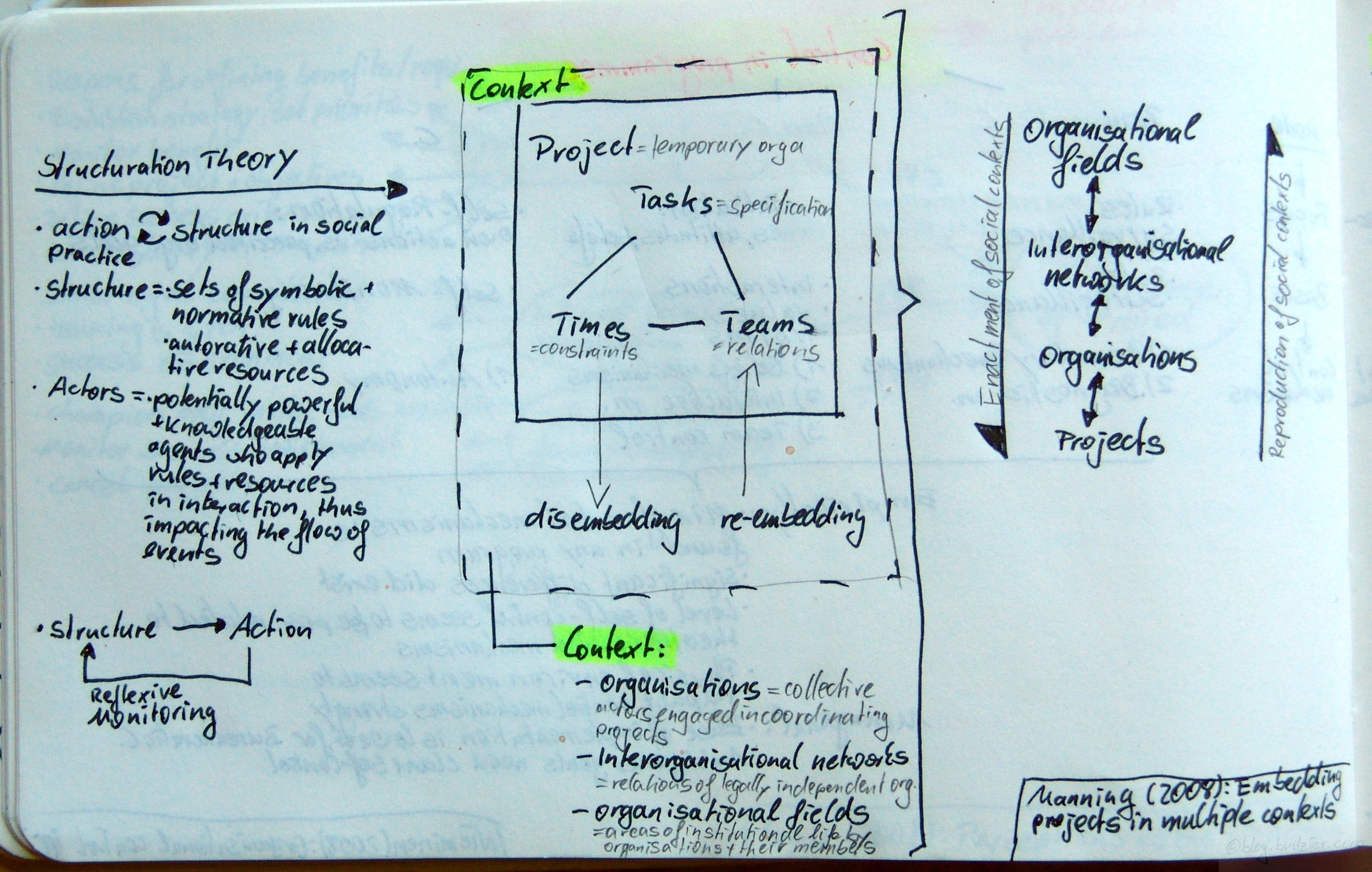

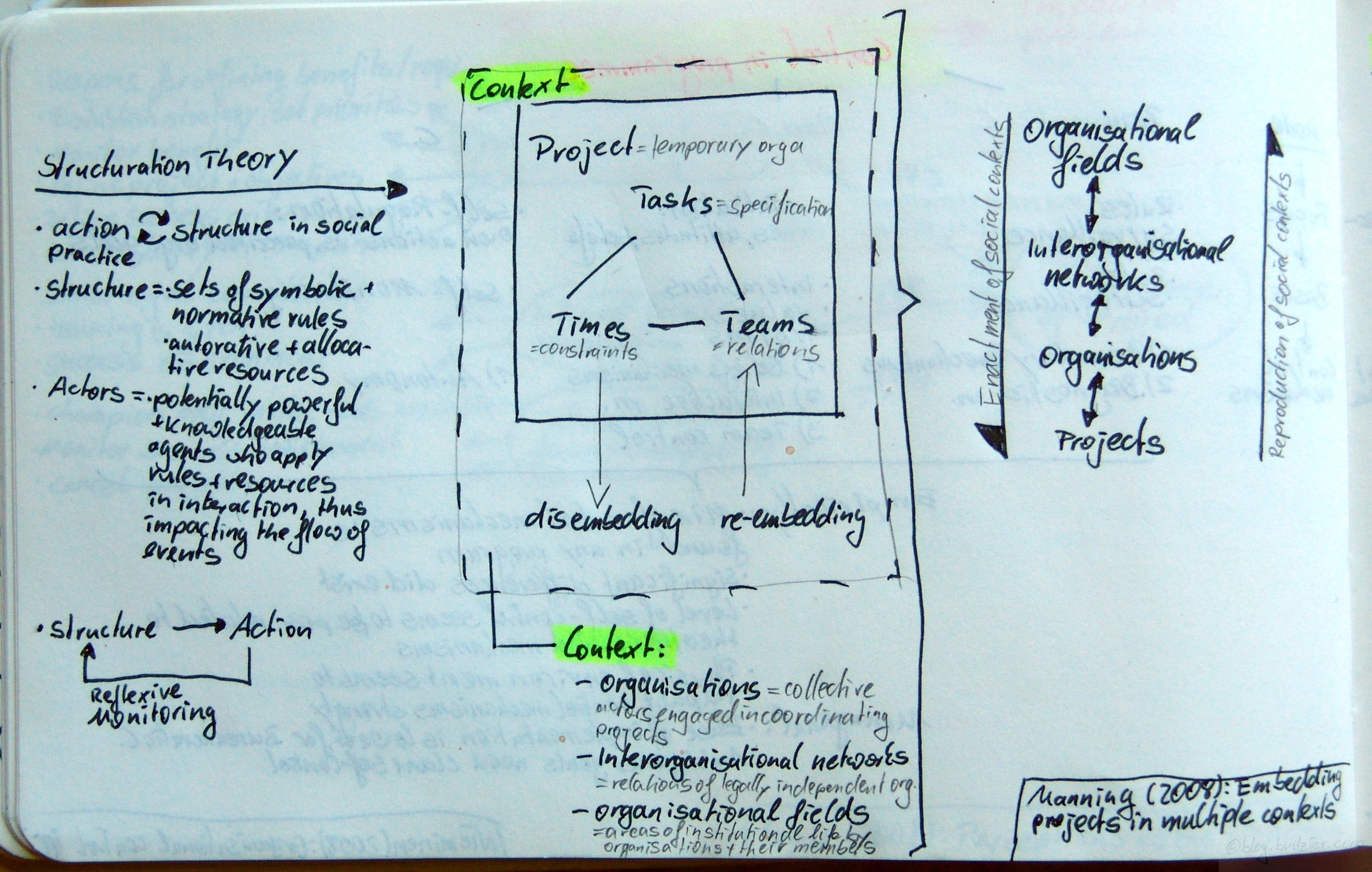

Manning, Stephan: Embedding projects in multiple contexts a structuration perspective; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 1, pp. 30-37.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.08.012

Manning argues that projects are embedded in multiple contexts at the same time. These context facilitate and constrain the project at the same time and dynamically he describes this as „projects partly evolve in idiosyncratic ways as temporary systems, embedding needs to be understood as a continuous process linking projects to their environments“ (p.30).

Manning bases his analysis on Structuration Theory. It’s premise is to analyse action and structure (to interdependent concepts) in practice. Structuration Theory is defined by three key concepts – (1) structure, (2) actors, and (3) reflexive monitoring.

Structure is the set of symbolic and normative rules found in organisations. Furthermore the structure is set by authoritative and allocative resources. Actors are defined as potentially powerful and knowledgeable agents, who apply rules and resources in interactions, thus impacting the flow of events. As such structure impacts actions, which in turn impacts the structure. Reflexive monitoring is exactly this feedback loop from action to structure.

Applying structuration theory to projects Manning builds the concept of the project as temporary organisation, which is characertised by its tasks (=specification), times (=constraints), and teams (=relations). The author furthermore notices a constant process of disembedding and re-embedding into different contexts.

Which contexts are there? Manning identfies three. (1) organisations which are the collecitve actors engagned in coordinating projects, (2) interorganisational networks which are relations of legally independent organisations, and (3) organisation fields which are areas of institutional life by organisations and their members. Projects are embedded in all three of these contexts at the same time.

Lastly, Manning describes two embedding and re-embedding activities. Enactment of social contexts takes place top-down, that is from organisation fields –> interorganisational networks –> organisations –> projects, whereas the reproduction of social contexts takes place bottowm up.

Posted in Context, Organisation, Organisational capabilities, Temporary organisation, Theory | 1 Comment »

Oktober 3rd, 2008

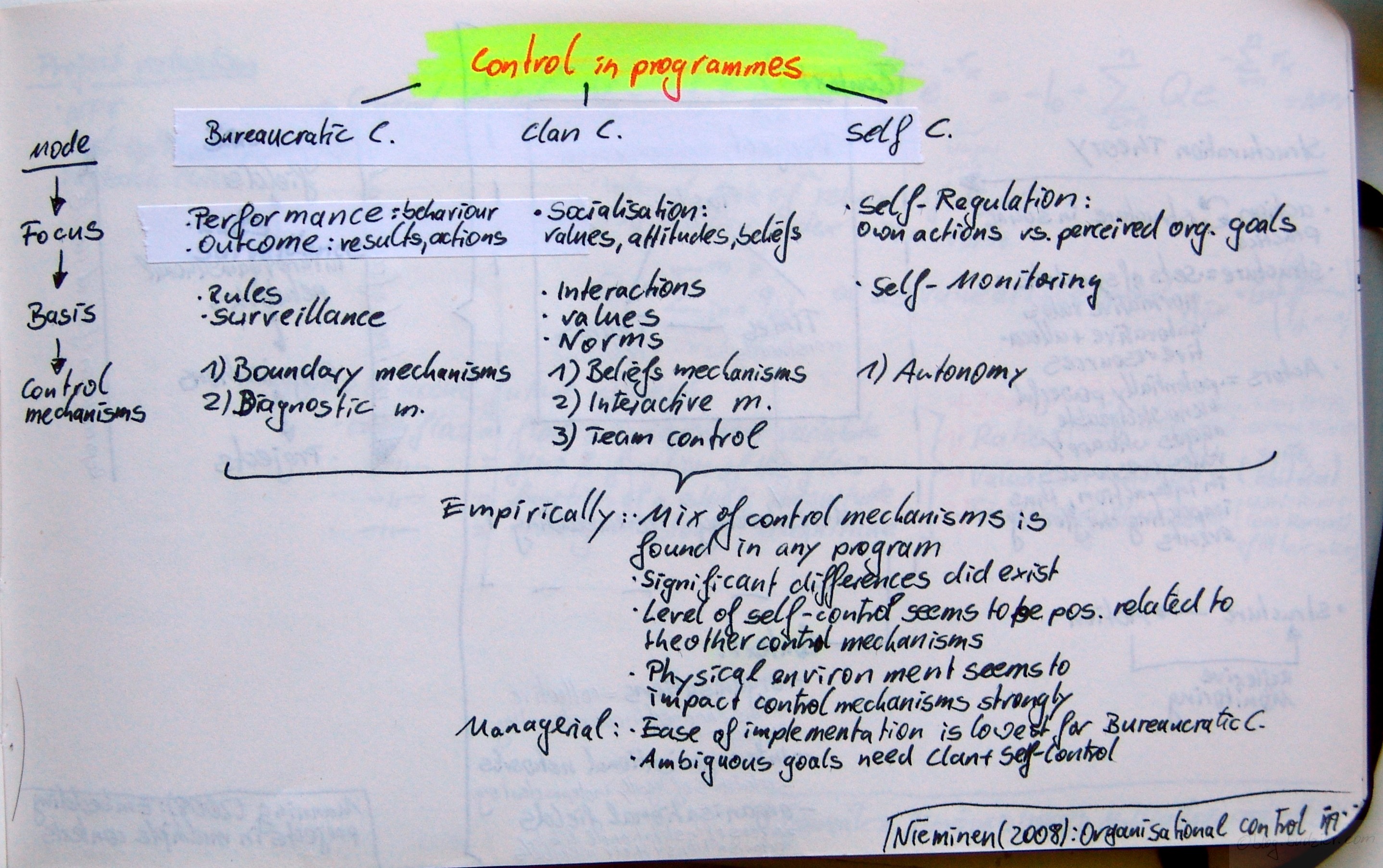

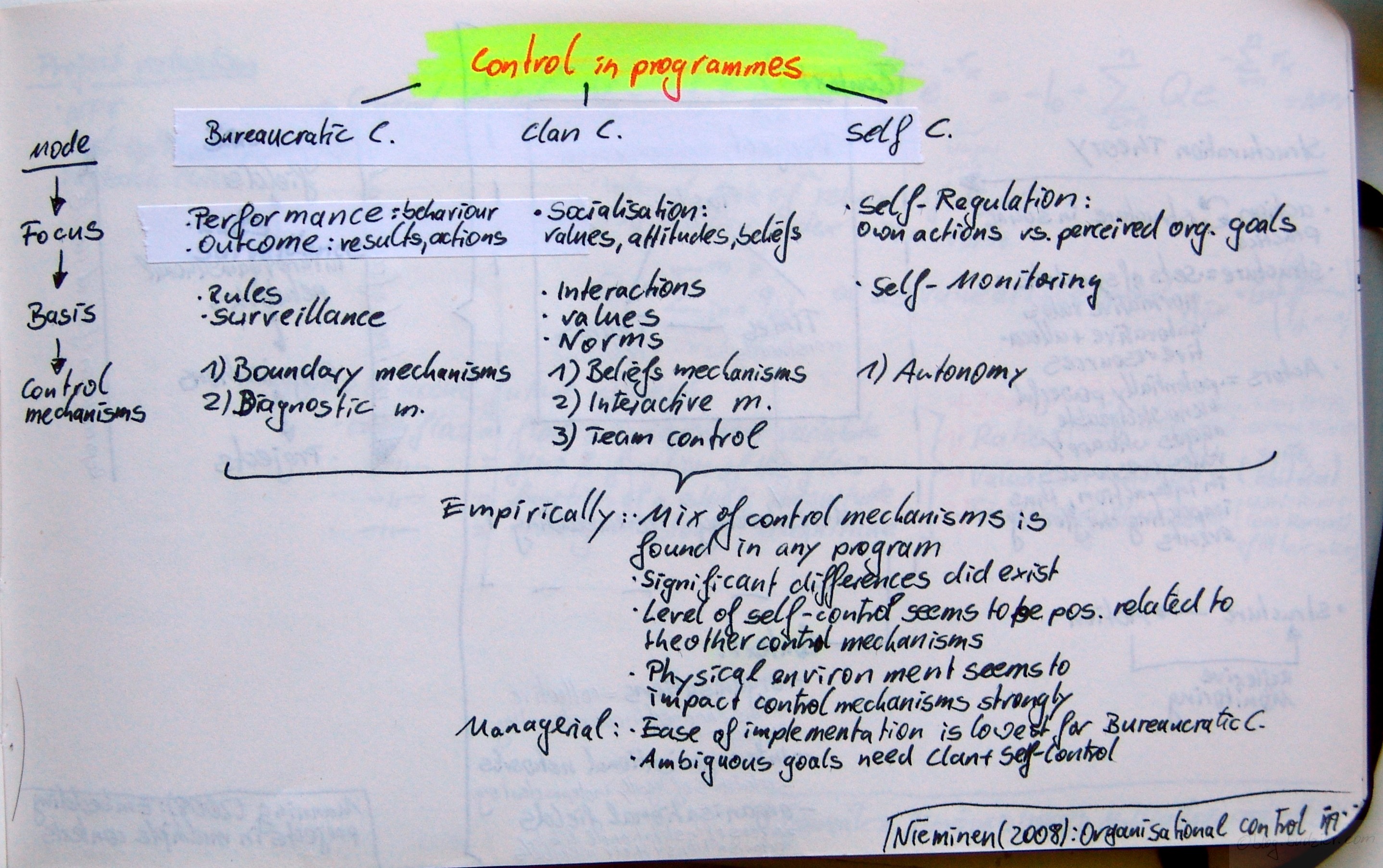

Nieminen, Anu; Lehtonen, Mikko: Organisational control in programme teams – An empirical study in change programme context; in: International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 26 (2008), No. 1, pp. 63-72.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.08.001

Nieminen & Lehtonen search for control mechanisms and modes in organisational change programmes. Therefore the authors investigated four cases of organisational change programmes with a significant share of IT in them. Overall they identified 23 control mechanisms, which are used complimentary rather than exclusively.

The identified control mechanisms fall into three basic categories – (1) Bureaucratic Control, (2) Clan Control, and (3) Self Control. For each of these Nieminen & Lehtonen describe the focus, basis, and mechanisms of control.

Bureaucratic Control focuses on performance, i.e., behaviour, and outcomes, i.e., results and actions. The basis of bureaucratic control are rules and surveillance. Mechanisms typically employed are boundary and diagnostic mechanisms.

Clan Control focusses on socialisation, i.e., values, attitudes, and beliefs. The basis of clan control are interactions, values, and norms. Mechanisms typically employed are belief mechanisms, interactive mechanisms, and team control.

Self Control focusses on self-regulation, i.e., own actions vs. perceived organisational goals. It is based on self-monitoring and typically useses autonomoy as control mechanism.

In their empirical study Nieminen & Lehtonen find that a broad mix of control mechanisms is found in any programme, though significant differences exist between programmes. Furthermore the level of self-control seems to be positively related to other control mechanisms. Lastely the authors show that the physical environment strongly impacts the control mechanisms.

In their managerial implications Nieminen & Lehtonen conclude, that although ease of implementation is lowest for bureaucratic control – environments with ambigous goals need mechanisms of clan- and self-control.

Posted in Control, IT Project, Multi-project management, Program Management | 3 Comments »

Oktober 3rd, 2008

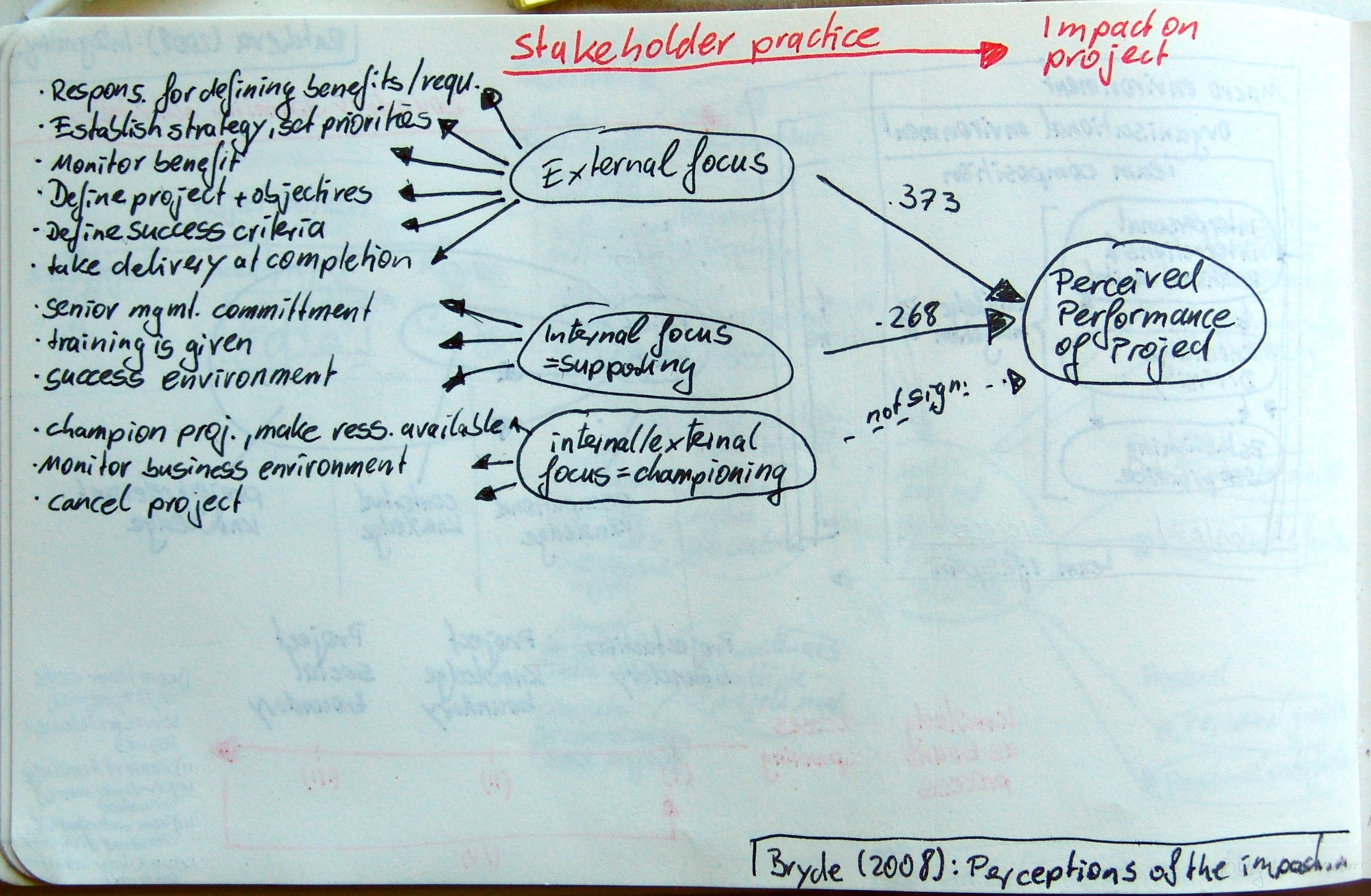

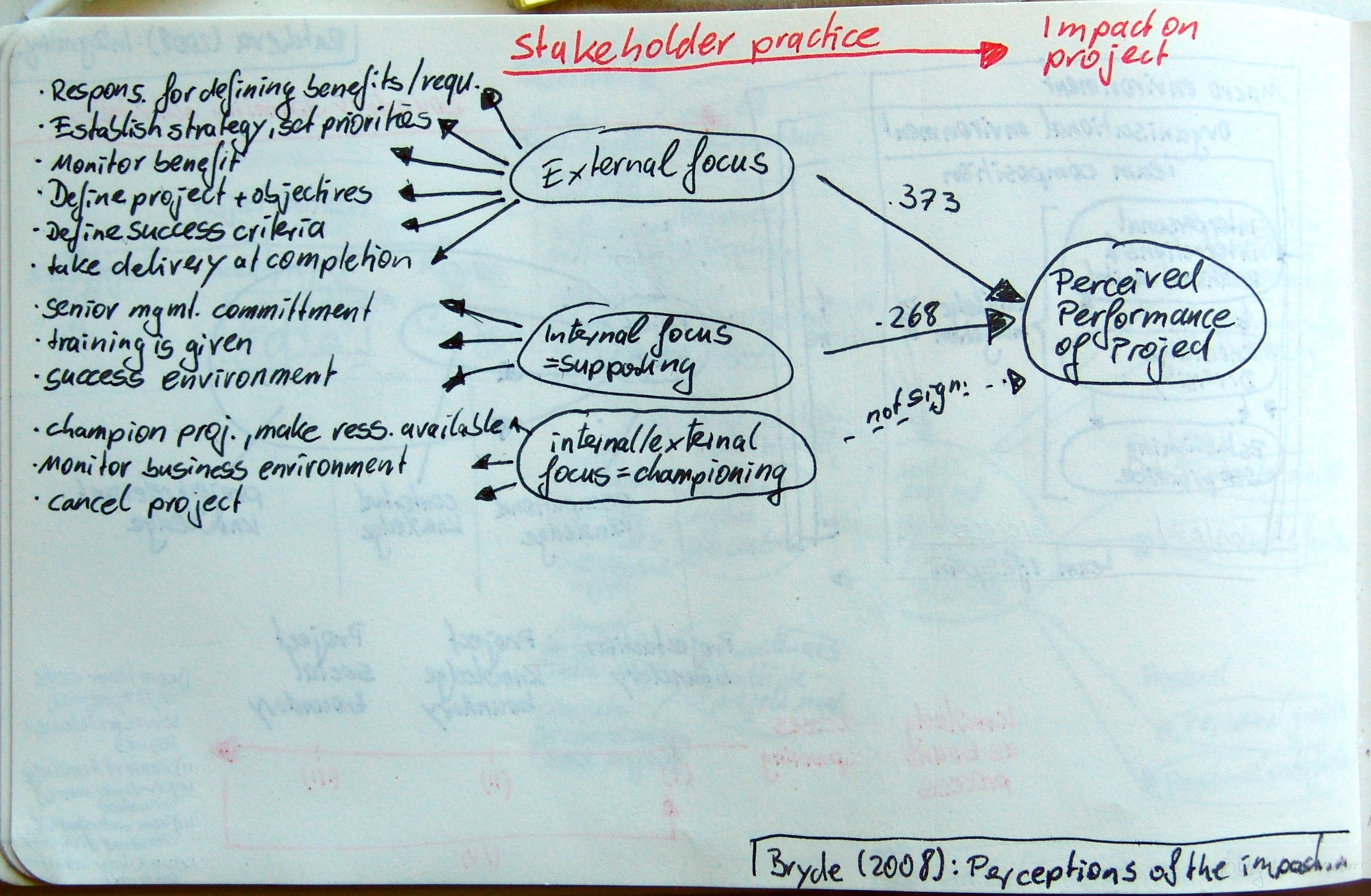

Bryde, David: Perceptions of the impact of project sponsorship practices on project success; in: International Journal of Project Management, in press.

Bryde investigates in this article the question which impact on the project stakeholder practice has.

The impact on the project is simply measured as perceived performance score of the project. The different practices are operationalised in three factors (with items sorted according to their factor loading)

- External focus

- Responsible for defining benefits and requirements

- Take delivery at completion

- Establish strategy, set priorities

- Define success criteria

- Define project and objectives

- Monitor benefits

- Internal focus = supporting

- Create an environment for projects to succeed

- Make senior management commitment

- Give training when necessary

- Internal/external focus = championing

- Cancel project if appropriate

- Champion project, make resources available

- Monitor business environment

Finally Bryde uses a stepwise regression to quantify the impact of each factor on the perceived project success score. Resulting in a two factor model where ‚External focus‘ (standardised β = 0.373) and ‚Internal focus‘ (standardised β = 0.268) impact the project success. Adjusted R2 is 0.326.

Unfortunately in this article the performance is just scored up although a multi-item measurement exists, factor analysis has not been employed. Furthermore the article does not detail the consistency of scale neither for the antecendents nor consequence (Cronbach’s Alpha) and does not test for heteroscedasticy or distribution. Thus this article falls short in advancing the development of a multi-item measurement of project success from a stakeholder point of view.

Posted in Stakeholder Management | 1 Comment »